Did Hittites exploit their people to build an empire?

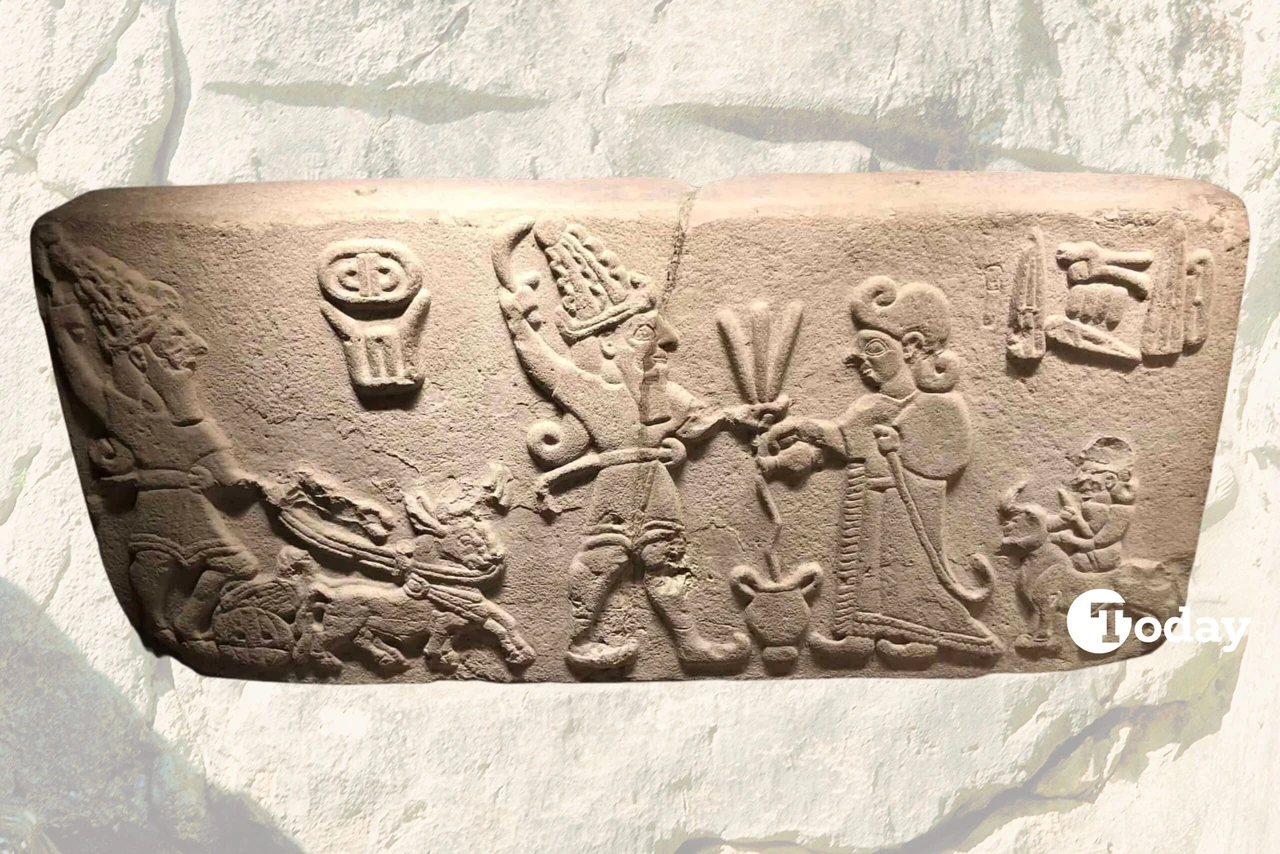

Malatya-Aslantepe city wall relief of King Sulumeli offering blood from a sacrificial bull to the Teshub as he gets off his chariot, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Türkiye. (Photo collage by Koray Erdogan/Türkiye Today)

Malatya-Aslantepe city wall relief of King Sulumeli offering blood from a sacrificial bull to the Teshub as he gets off his chariot, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Türkiye. (Photo collage by Koray Erdogan/Türkiye Today)

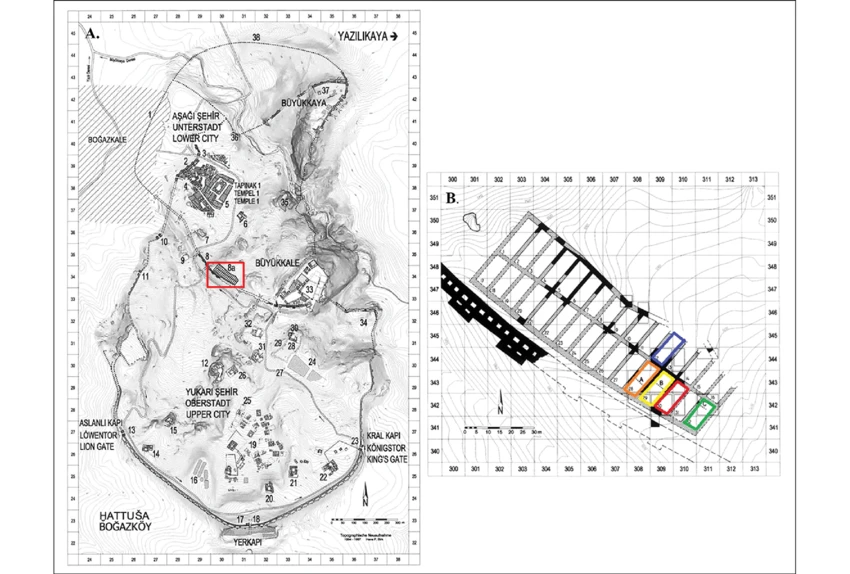

Archaeologists have uncovered what may be the world’s largest known ancient grain silo, buried beneath the ancient capital of Hattusa in modern-day Türkiye. Holding remnants of hundreds of tons of carbonized grain, this massive underground storage facility offers rare insight into the economic and political strategies of the Hittite Empire over 3,500 years ago.

The discovery, made in 1999, highlights how grain—especially wheat and barley—was not merely a staple food but a powerful tool for governance, taxation, and control.

Ancient bureaucracy in clay

The process of collecting, storing, and redistributing grain was meticulously documented on clay tablets, proving the existence of a highly sophisticated administrative system. These records detail not only the amount of tax grain collected but also logistical routes and storage procedures.

This level of bureaucratic precision shows that the Hittite state maintained tight control over the food supply, ensuring that the rural population’s output directly benefited the central government.

A monument to state power

The 32-room silo discovered in Hattusa was a centralized depot for grain collected through a systematic taxation structure. Under the Hittite law, all commoners—excluding the elite—were obliged to either work directly for the king or give a portion of their agricultural products as tax.

Two key terms defined this system:

- Luzzi required farmers to labor on royal fields on designated days.

- Sahhan mandated taxes in kind, including grain, livestock, and artisanal goods.

This underground silo not only symbolizes the logistical might of the Hittite state but also its ideological power: it stood as a physical reminder of the state’s reach into rural lives.

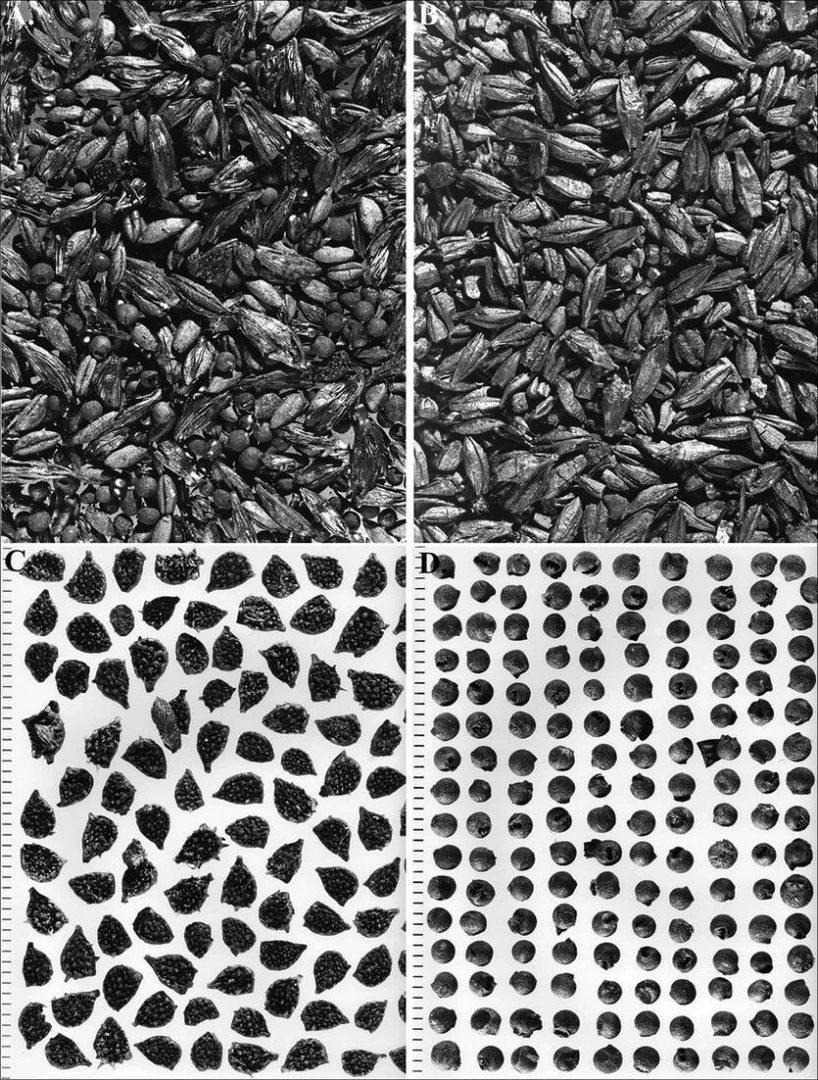

Agriculture as exploitation

Analysis of the stored grain revealed that most of it was produced with minimal inputs—little water, fertilizer, or tools. Farmers, under pressure to meet tax demands, cultivated grain in the most resource-efficient ways possible, especially in remote villages with limited access to water or fertile land.

This suggests a system where peasants survived on the edge, while rulers accumulated vast reserves of grain, enhancing their wealth and reinforcing their political dominance.

Wheat as a weapon of rule

In the Hittite Empire, grain was more than nourishment. It was a political asset.

- It was used as tribute in diplomatic relations.

- It fed armies during wartime.

- It became a means of control in times of famine.

The centralized accumulation of grain ensured the king’s dominance even during crises, allowing the state to thrive while the rural population struggled for subsistence.

The fire that ended an era

But centralization had its risks. A massive fire eventually consumed the Hattusa silo, carbonizing its contents and ironically preserving them for modern-day archaeologists. While the blaze was destructive, it also turned the structure into a time capsule of ancient economic life.

Whether the fire was accidental or an act of sabotage remains unknown. However, the Hittites never rebuilt another silo of such scale, indicating that the disaster marked a turning point in their agricultural strategy.

Political control through grain

This monumental find in Hattusa shows how early states like the Hittite Empire amassed power not just through armies or alliances—but through control of food. The silo stands as archaeological evidence of a centralized, exploitative agricultural system that fueled a kingdom and symbolized its might.