In central Türkiye’s Kayseri province, researchers are using 3D printers to complete missing limbs and other body parts on fossils dated to 7.7 million years ago. The remains—found near the Yamula Dam by a goat herder in 2017 and excavated since 2018—include saber-toothed cats, giraffes, elephants and mammoths, rhinos, three-toed horses, and “bovid” species, meaning hollow-horned sheep, goats, and antelopes, alongside turtles and pigs.

The team is preparing the finds for public display at the under-construction Kayseri Paleontology Museum, after cleaning, conservation, and “mounting” work—setting up the specimens for exhibition—at the Kayseri Science Center.

Specialist anthropologist Omer Dag said the fossils rarely appear as complete skeletons; teams usually recover heads, feet, and limbs separately, then identify the species before moving to 3D scanning. He noted that scanning has brought better results for reconstruction.

Dag explained that they long filled gaps by taking molds, but new 3D printers purchased by the municipality let them do the same job without exposing specimens to chemicals, which he described as a healthier method for the bones.

Emphasizing why mounting matters for visitors, Dag said the team can read a fragment instantly, but displays must make the anatomy legible to the public. “We complete the missing parts with the sections produced by the printer after drawings,” he said. He added that institutions often outsource such work to China, whereas with metropolitan support they now do it locally at far lower cost.

“A giraffe mounting used to be ₺2–3 million, and we did it for ₺14,000–15,000,” he said.

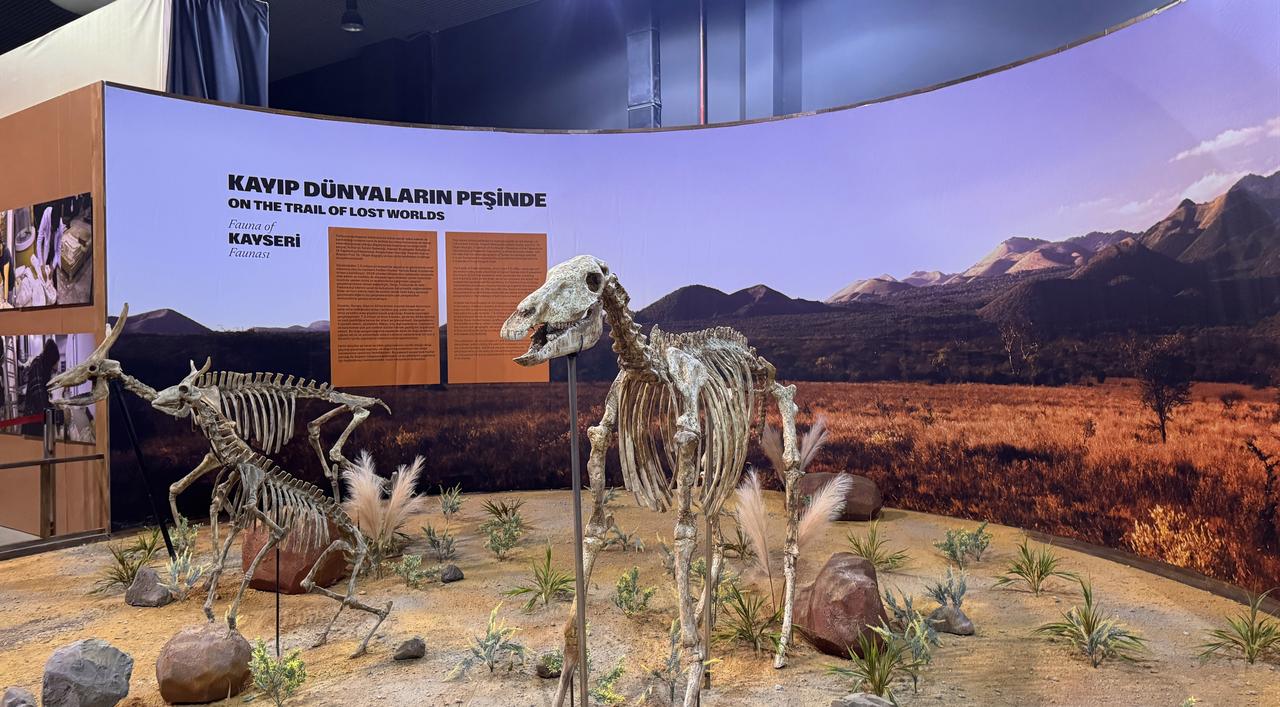

Dag reported that giraffe, rhino, and elephant mounts are already finished; there is also a three-toed horse and two hollow-horned specimens—one comparable to a modern antelope and another to a gazelle—while the saber-toothed cat mount is nearing completion.

He said the goal is for museum visitors to see each animal of the fauna, properly mounted and at a reasonable cost.

Anthropologist Berk Durmus underlined that the printed material is a plastic-like substance without adverse effects for human health.

He outlined the workflow after field recovery: the team determines genus and species, compiles measurements from scholarly articles, and executes repairs using drawings guided by those mathematical data. “As a result of data analyses, we slice the models in 3D printer programs and send them to the printers,” he said.

Once installed in the new museum, the mounted specimens are expected to take visitors on a journey to the region’s deep past—about 7.7 million years ago—showcasing the large-bodied “megafauna” that once roamed what is now Kayseri.