Following Israel’s recent airstrikes that reportedly killed several top Iranian military officials, including Iran’s Chief War Commander Ali Shadmani and senior intelligence figure Gholam Reza Mehrabi, attention has turned to Iran’s deeply rooted political history—one marked by assassinations, coups, and power struggles spanning over two and a half millennia.

According to Israeli military statements, Shadmani, described as the “closest figure to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei,” was killed in a staffed command center in central Tehran following what was described as a sudden opportunity enabled by “precise intelligence.” Shadmani, who had taken command after the death of Lt. Gen. Gholam Ali Rashid just days earlier, reportedly held the highest operational authority over both Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and its regular army.

Earlier, Israeli strikes had also targeted missile facilities and high-ranking military officials, including Mohammad Bakeri, a senior commander in Iran’s missile forces. The air raids, which began on June 13, killed at least 78 individuals, including military commanders and scientists, according to Iran’s UN envoy. Was this an intelligence failure for Iran? Has Iran experienced such things throughout its history?

While the current crisis unfolds in real time, the pattern of political assassinations has been a defining feature of Iran’s political landscape since the Persian Empire. Founded in the 6th century B.C. by Cyrus I, the empire spanned vast territories and required central authority to manage ethnic diversity and external threats. However, internal power struggles often led to betrayal and killings among royal and military elites.

Struggles for the throne frequently turned violent. Xerxes I, for example, was assassinated in 465 B.C. by his own commander Artabanus, who infiltrated the royal court to carry out the murder. Artabanus briefly seized power before being overthrown by Artaxerxes II. These internal coups not only weakened central authority but made the empire more vulnerable to external adversaries.

The accession of Darius I was itself the result of an assassination. Darius and his allies killed the Magus Gaumata, who had seized the throne by posing as Cambyses II’s brother. Similarly, during the later Achaemenid period, Artaxerxes III and his heir were both poisoned by their own general Bagoas, who sought to control succession from behind the scenes.

The Sassanid Empire faced similar instability. Husrev II was assassinated by his son Kavadh II, who also ordered the murder of 18 of his brothers to eliminate rivals. These internal purges contributed significantly to the empire’s eventual collapse.

Political killings continued well into the medieval Islamic period. In 1092, Nizam al-Mulk, the Persian vizier of the Seljuk Empire, was assassinated by the Hashshashis—a secretive group tied to the Ismaili sect. Disguising themselves as dervishes, these agents became notorious for targeted assassinations of political figures across the Middle East.

Even during the Safavid era, court intrigues and assassinations were common. Shah Abbas II, like his predecessors, ruled amid a web of internal power struggles.

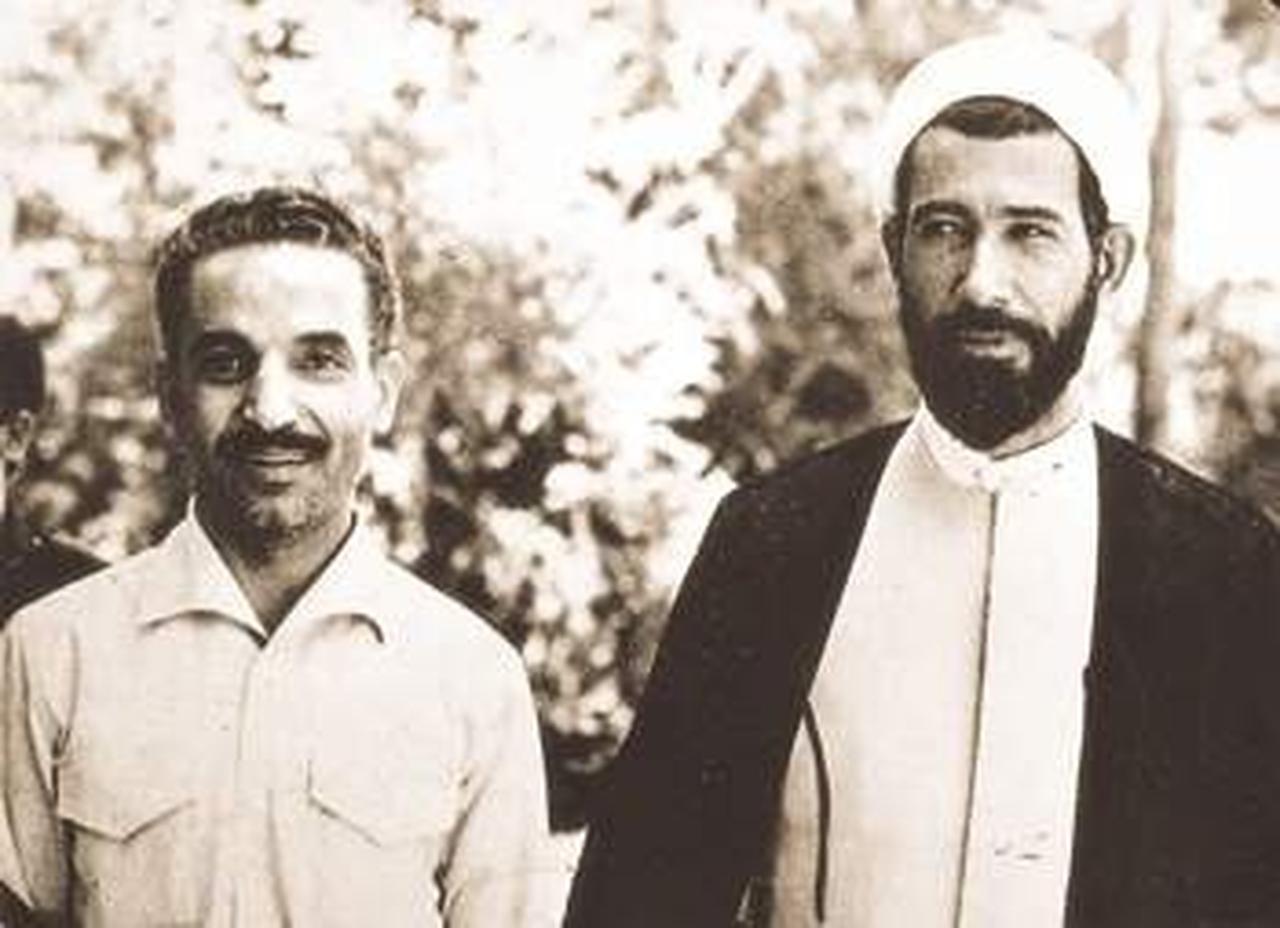

In the 20th century, Reza Shah and later Mohammad Reza Shah faced numerous assassination plots amid their modernization efforts and growing authoritarianism. The 1979 Islamic Revolution, which toppled the monarchy, did not end these trends. Instead, the early years of the Islamic Republic saw high-profile killings, including the 1981 assassinations of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Rajai and Iranian President Mohammad Javad Bahonar.

The Israeli army has characterized its recent operations as delivering a “strategic blow” to Iran’s war command structure, eliminating key figures shaping Iran’s offensive capabilities. According to the Israeli military, Shadmani directly oversaw military plans aimed at Israel.

While Iran has yet to issue a detailed response to Israel’s latest claims, the cycle of power, betrayal, and assassination that has long defined the region’s politics continues to play out—this time in the heart of a nuclear-capable state.