Scientists, in a recent study published in the European Journal of Archaeology, have identified three Neolithic obsidian blades discovered in Poland as originating from Mount Nemrut, a volcanic complex in Bitlis, eastern Türkiye.

The research highlights that this finding marks the furthest western distribution of this volcanic glass, located more than 2,200 kilometers from its geological source.

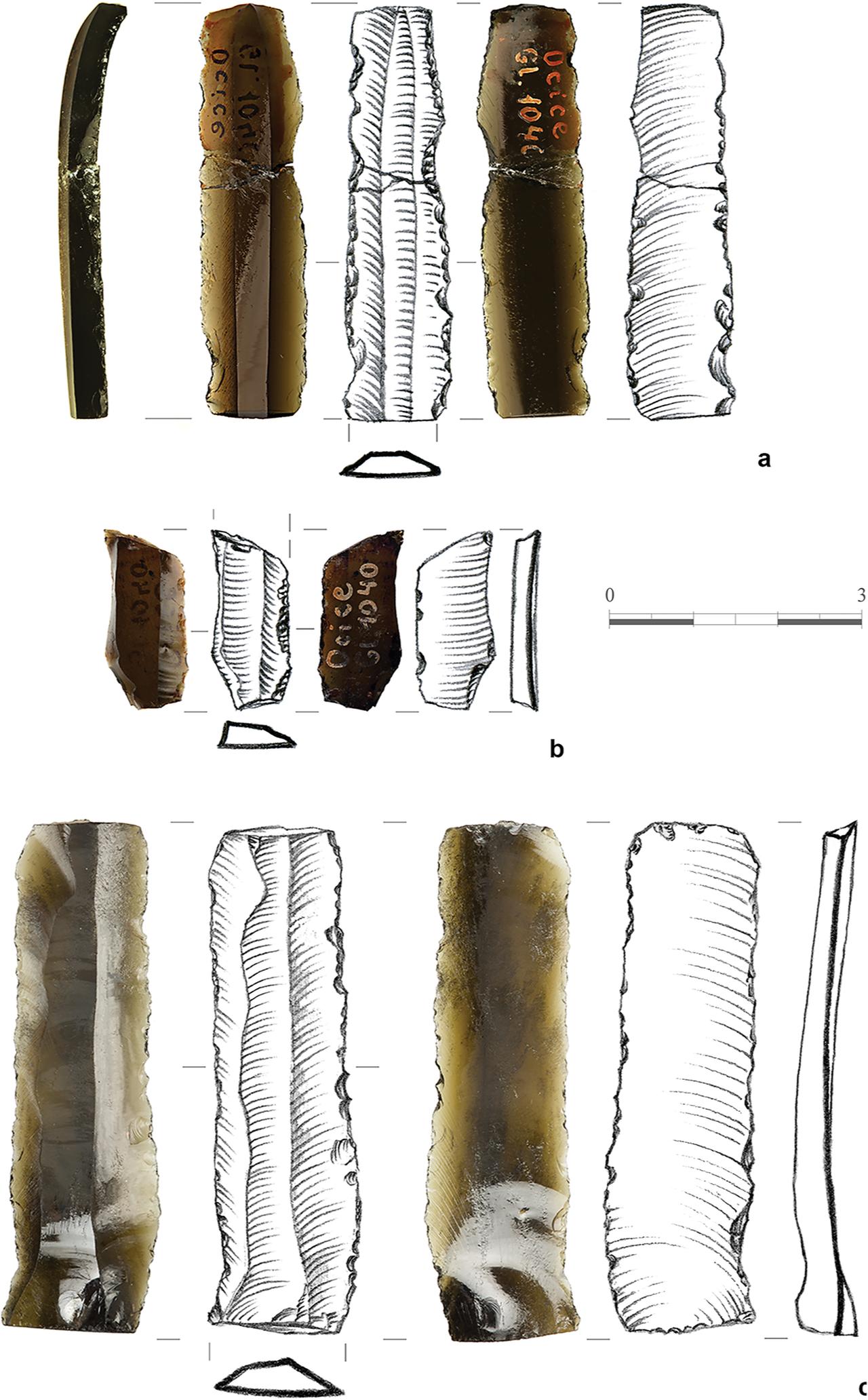

Two of the blades were recovered from the Raciborz-Ocice settlement in Silesia, an area of southwestern Poland.

Excavations at the site began in the late 19th century, with material later transferred to regional museums.

Despite wars, looting, and museum reorganizations, a portion of the collection survived, including obsidian artefacts that stood out from the more common local stone tools.

A third blade was unearthed during a surface survey in Silesia between 1961 and 1970 and has since been displayed in the Archaeological Museum in Wroclaw.

While the exact context of this find remains unclear, its technological features closely resemble the Raciborz-Ocice examples.

Geochemical testing using non-destructive energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) confirmed that all three blades originated from the Mount Nemrut source.

Obsidian from this region is chemically distinct due to its high zirconium content, which sets it apart from Carpathian volcanic glass typically found in Neolithic Poland.

The Nemrut artifacts are considerably rare, as most Polish obsidian derives from nearer sources in Slovakia and Hungary.

Their presence in Silesia pushes the known western boundary of Mount Nemrut obsidian more than threefold compared to previous records.

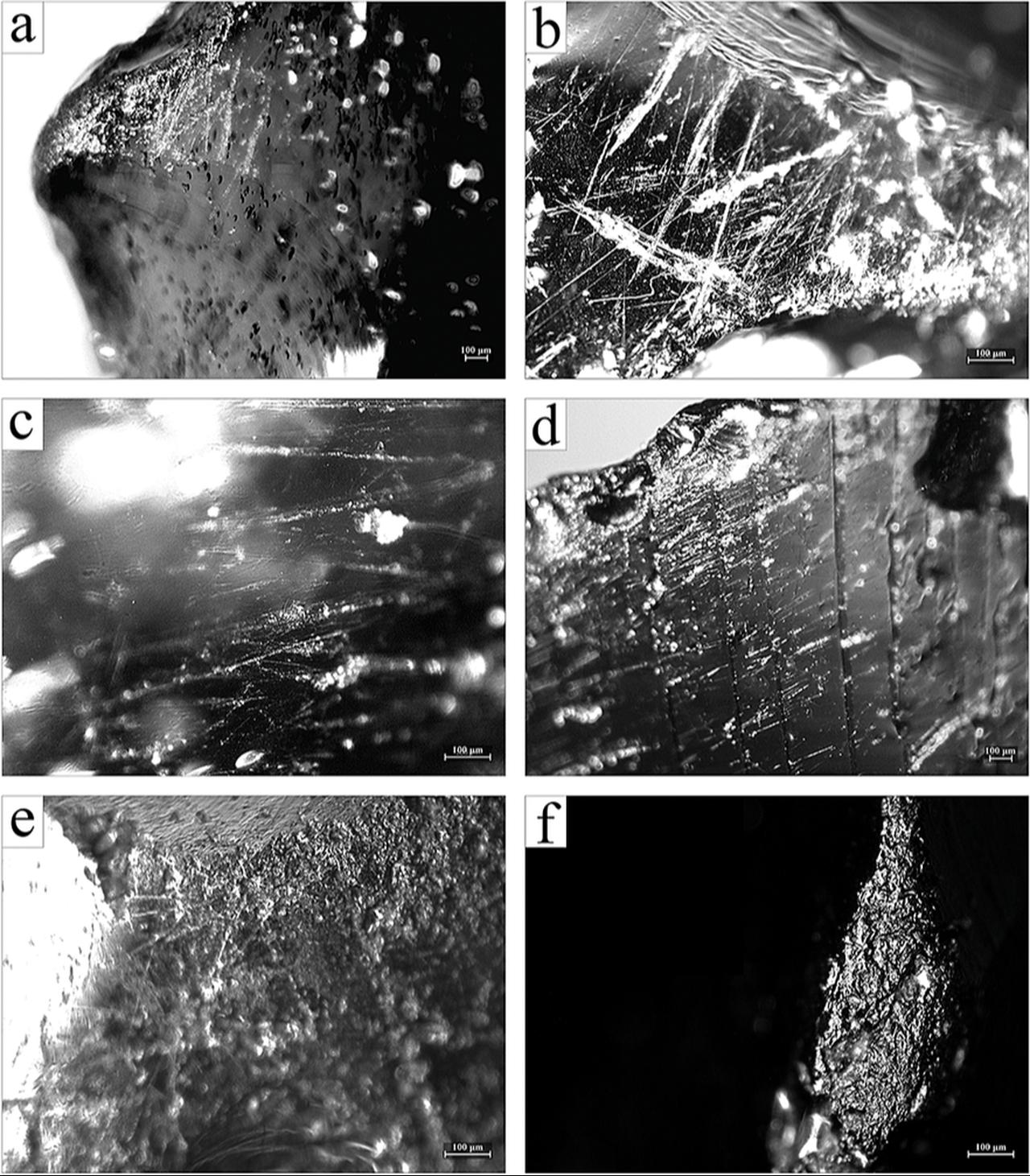

Microscopic wear traces on the blades suggest they were employed as scrapers, saws, and burins, possibly for working animal hides or harder materials.

Yet researchers stress that these marks should be interpreted with caution, as the artifacts may have had long and complex biographies before reaching Poland.

Beyond practical functions, obsidian carried symbolic weight in Neolithic societies. Like exotic shells and jade axes found far from their sources, such volcanic glass was part of networks of exchange and gifting.

These items may have been used to strengthen social ties or reflect status within communities.

The discovery of Mount Nemrut obsidian in Poland fits into a broader pattern of long-distance interactions across Neolithic Europe and Southwest Asia.

Similar “exotic” finds, including Mediterranean shells and Caucasian obsidian, have been traced across thousands of kilometers.

Whether these ancient Anatolian blades reached Poland through gradual exchanges or direct, directional conveyance remains uncertain.

What is clear is that they represent a tangible link between Anatolia and Central Europe during the Neolithic, demonstrating that communities were more interconnected than previously believed.