Underwater archaeologists in Türkiye have uncovered a remarkable set of 15 glass perfume bottles from a shipwreck believed to be more than 1,000 years old, lying off the coast of Kas in southern Türkiye. The ship, thought to be a commercial vessel of Eastern Mediterranean origin, is estimated to have sunk around the 10th or 11th century.

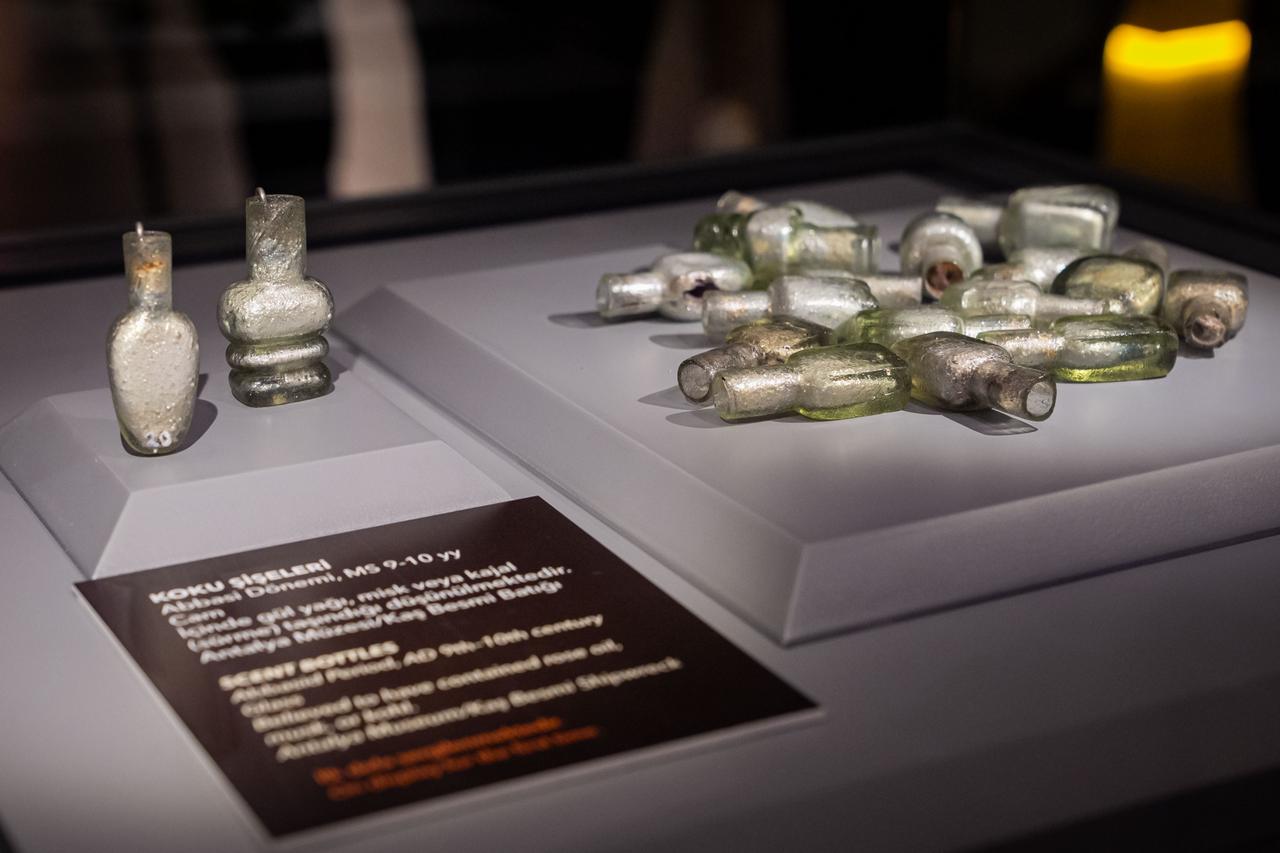

The bottles, each about 6–7 centimeters in height, are believed to have once contained luxury scents such as rose oil, musk, or amber—substances commonly produced and traded in the Levant and Egypt during the Abbasid period. The discovery was presented for the first time to the public during the International Archaeology Symposium and the Golden Age of Archaeology Exhibition held at the Presidential Library in Ankara, with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in attendance.

According to Associate Professor Hakan Oniz, head of the Department of Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Properties at Akdeniz University and director of the excavation, the shipwreck belonged to a vessel likely originating from the coastal cities of Palestine or Gaza. The cargo included amphorae—large ceramic jars—used to transport olive oil produced in the region.

In one of these amphorae, archaeologists found actual olive pits, supporting the theory of the ship's cargo origin. While investigating the wreck, a team member came across a small glass vessel, prompting further exploration that led to the recovery of 15 intact glass containers. Although laboratory analysis is ongoing, Oniz estimates with high certainty that the vessels were used to store perfume or possibly kajal—a traditional eye cosmetic.

“These glass vessels are not surprising,” Oniz said. “They were made using a mold-blowing technique, which is characteristic of glass-working in the Syria-Palestine region.”

Glass-making and the art of perfumery were already well-developed in the Eastern Mediterranean by this time, while Europe had yet to cultivate its own perfume culture. “Perfume and glass technologies spread from the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe,” Oniz explained, adding that the recovered bottles could represent some of the earliest evidence of perfume export from East to West.

Popular scents of the era—rose from Damascus, musk from Egypt, and amber from across the region—were widely known and used in daily life in the Eastern Mediterranean. These discoveries underscore the area’s central role in early global trade routes and cultural exchange.

Türkiye's role in underwater archaeology is well-established, and according to Oniz, it goes back far beyond the mid-20th century. “The field of underwater archaeology, though formalized globally in the 1960s, actually traces its roots to the 1890s in the Ottoman Empire, when Osman Hamdi Bey—then director of the Istanbul Archaeology Museum—conducted studies on the island of Farmakonisi,” he noted.

Oniz also emphasized the uniqueness of the region: “This land witnessed the rise of the first settlements, first cities, first maritime activities, and now it is giving us insight into the first sailing vessels.” To date, more than 400 shipwrecks have been documented along Türkiye’s Mediterranean coast, with excavations continuing under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

Among the ongoing efforts is the “Heritage for the Future” project, through which four distinct shipwrecks—ranging from the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Hellenistic and Early Roman periods—are being excavated at various coastal sites including Kumluca, Adrasan, and Kas.

Oniz described underwater archaeology as a discipline that continually surprises even seasoned experts—not with gold or treasure, but with unexpected insights into the past. “The unknowns of archaeology are what truly excite us,” he said. “Sometimes it’s turquoise or aquamarine-colored glass ingots. Sometimes it’s perfume bottles. These are the real treasures that unlock history.”

He also highlighted the international makeup of their excavation teams, which include archaeologists and postgraduate students from Australia, Argentina, Japan, and beyond. Many come through global organizations such as UNESCO, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), and the World Underwater Federation (CMAS), gaining hands-on experience during their time aboard the research vessel.

“Türkiye is clearly a world leader in underwater archaeology,” Oniz said. “But it’s not because of us—it’s because of this extraordinary geography we are privileged to work in.”