A recently identified underwater copper mine off Heybeliada, an island in the Marmara region near Istanbul, has revived an unusual story that reaches back to Aristotle, to a famous sculpture school in ancient Greece and to a highly specialized trade in so-called “diver’s copper.”

We spoke with archaeologist Associate Professor Ahmet Bilir about his research that connects an unusual underwater copper mine off the coast of Istanbul’s Heybeliada with a rare material once described by Aristotle as “diver’s copper,” revealing a remarkable link between Türkiye’s Marmara region and the prestigious bronze workshops of ancient Greece.

The story begins with a short but striking passage in Aristotle’s work "De Mirabilibus Auscultationibus" (On Marvelous Things Heard). In section 58, paragraph 834, Aristotle reports that divers extracted copper from a mine lying under two fathoms of water—around 3.6 meters—near what is now known as Heybeliada.

| Aristotle, De Mirabilibus Auscultationibus, §58 |

|---|

| Demonesus, the island of the Chalcedonians, received its name from Demonesus, who first cultivated it. The place contains the mine of cyanos and gold-solder. Of this latter the finest sort is worth its weight in gold, for it is also a remedy for the eyes. In the same place there is also copper, obtained by divers, two fathoms below the surface of the sea, from which was made the statue in Sicyon in the ancient temple of Apollo, and in Pheneus the so-called statues of mountain-copper. On these is the inscription— ‘Heracles, son of Amphitryon, having captured Elis, dedicated them’. Now he captured Elis guided, in accordance with an oracle, by a woman, whose father, Augeas, he had slain. Those who dig the copper become very sharp-sighted, and those who have no eyelashes grow them: that is why also physicians use the flower of copper and Phrygian ashes for the eyes. |

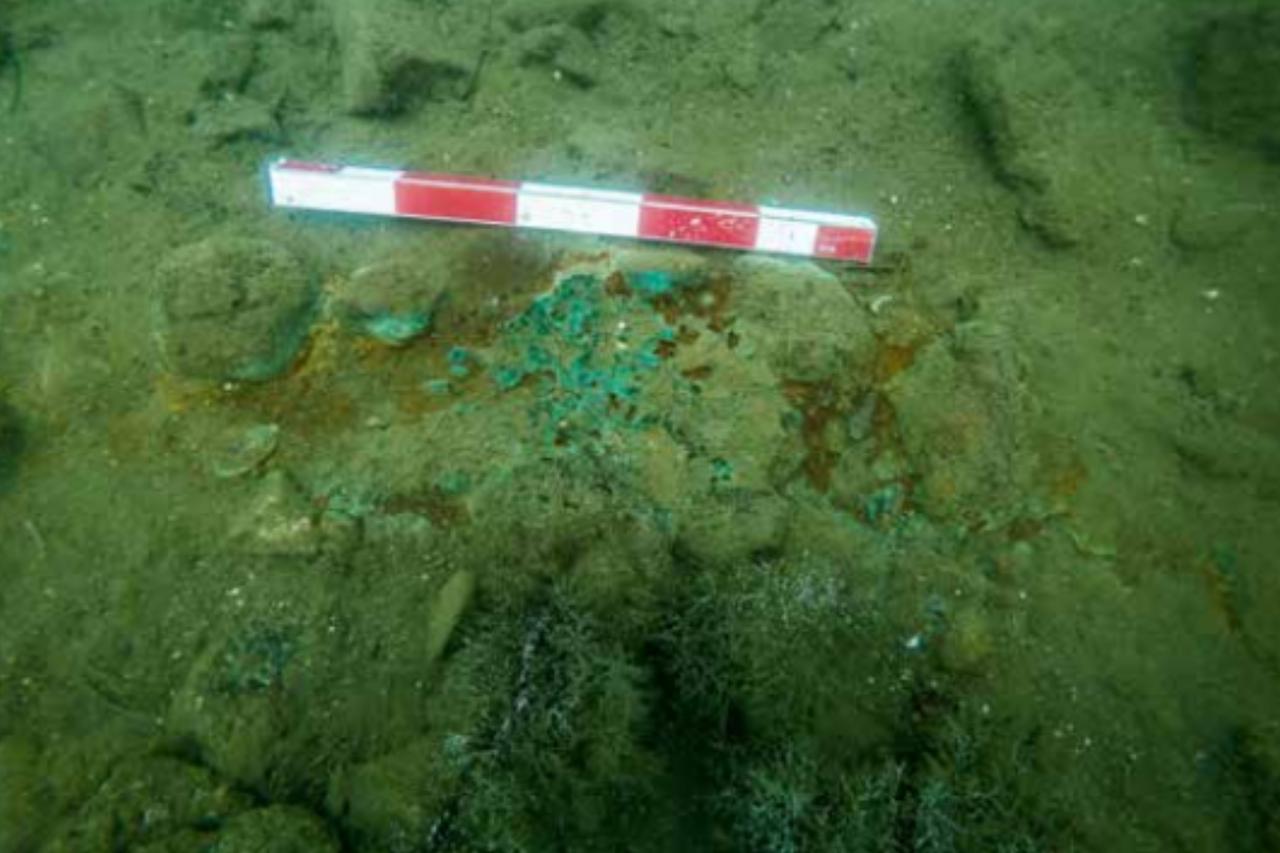

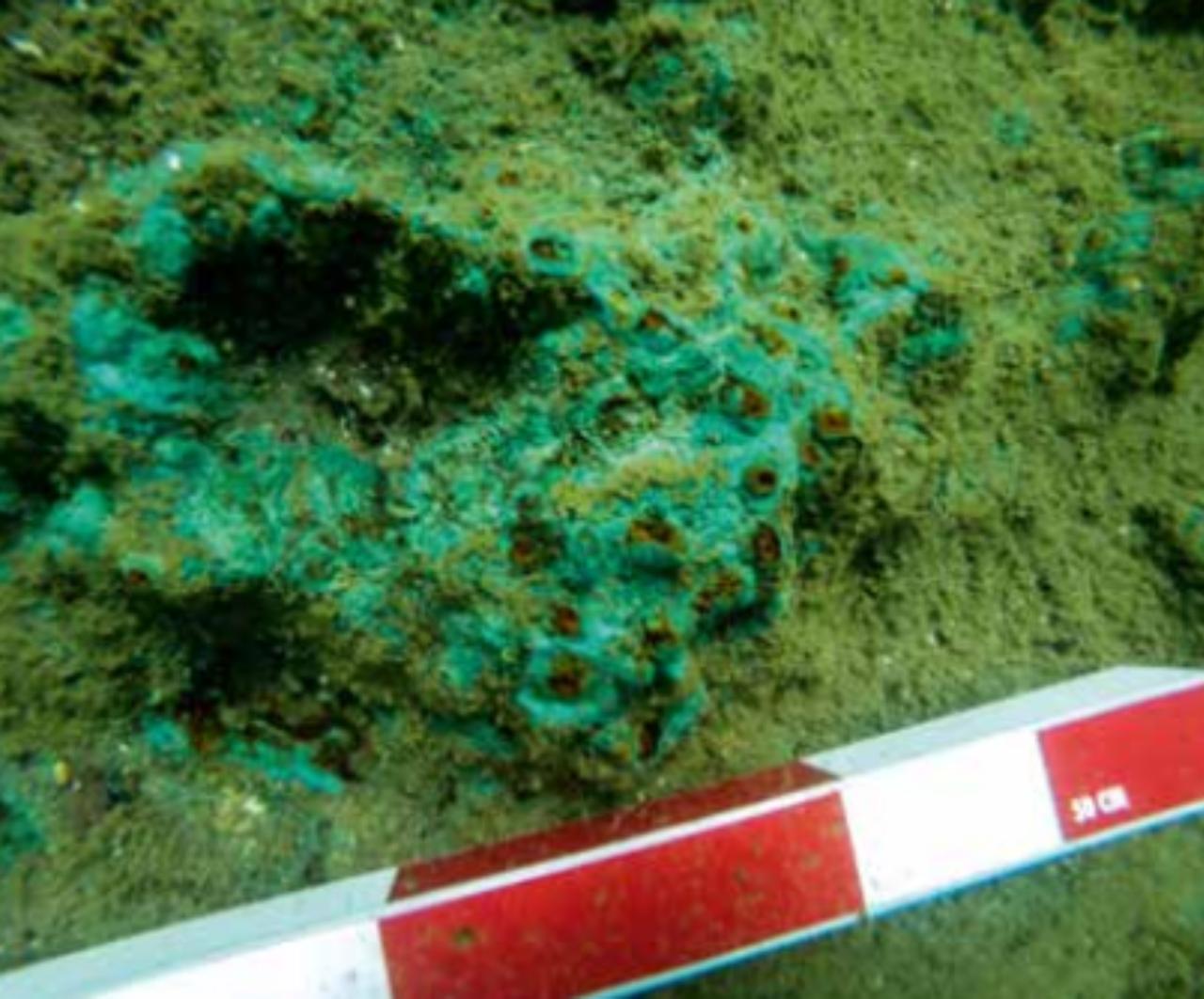

In 2018, as part of the Underwater Survey of Northeastern Marmara, archaeologist Bilir and his team carried out a 15-day underwater survey in Camlimani Bay, on the coast of Heybeliada. Because the water was relatively shallow in much of the bay, the team mainly relied on free-diving techniques and then switched to equipment-assisted dives as the depth increased toward the inner parts of the cove.

During this campaign, they identified a copper mine dated to the Late Classical Period of the ancient Greek world, directly matching Aristotle’s description of copper being brought up from underwater by divers.

Bilir says Aristotle also provided the name of this material as khalkon kolymbeten (Greek: chalkon kolymbeten), meaning “diver’s copper.” According to him, this copper had both artistic and economic value and was reportedly used in the Temple of Apollo in Sicyon, a Greek city known for its prestigious sculpture school. He adds that it was also mentioned in connection with Pheneus, where it was recognised as a type of yellow copper.

Bilir defines this material as a “niche market product,” meaning it was produced in limited quantities for a very selective clientele, likely members of artistic and religious circles, who valued its special origin and symbolic meaning.

According to Assoc. Prof. Ahmet Bilir from Duzce University, copper mining significantly contributed to Heybeliada’s local economy in antiquity. However, the underwater mine at Camlimani Bay appears to have held a unique status. He notes that Aristotle’s information suggests that this underwater copper was shipped to Sicyon, where a prominent sculpture school thrived and trained masters such as Lysippos.

Lysippos, who served at the court of Alexander the Great, is believed to have worked with high-quality copper and bronze. Bilir adds that it is possible that the copper extracted from Heybeliada’s seabed was among the valuable materials used in the statues linked to Lysippos’ artistic circle, especially those dedicated to the Temple of Apollo.

Bilir highlights that, in the religious culture of the time, communities sought to honor their gods with offerings that required exceptional effort. He explains that copper extracted from underwater required both diving skills and technical labor, making it symbolically valuable. Its extraction process itself may have enhanced its prestige, especially for statues meant for sacred settings.

He adds that, for this reason, diver’s copper was not only economically valuable but also spiritually and symbolically meaningful. This unique combination of purpose, artistry and difficulty explains why it occupied a special place in the ancient trade network.

Bilir also draws attention to the skills required to mine copper underwater in that period. He says ancient divers were experienced enough to work with simple breathing devices and stay submerged for extended periods. Their expertise made it possible to maintain an underwater mining operation, consistent with Aristotle’s description.

He concludes by suggesting that the underwater mine at Camlimani Bay, Aristotle’s written testimony and the artistic fame of Sicyon together indicate a trade route connecting Heybeliada’s divers to the sculptors of ancient Greece. In Bilir’s words, diver’s copper stood at the intersection of art, religion and commerce, becoming almost as valuable as gold in the niche markets of the ancient Mediterranean.