The Dutch city of Rotterdam, a “majority minority city” home to over 180 nationalities, is set to open its new art museum about migration. Fenix is located on a landmark site in Rotterdam’s historic docklands, where countless people once departed and arrived, all in search of a better future.

The museum explores the universal experience of migration, and Queen Máxima, who was born in Argentina, inaugurated Fenix today, on Thursday, May 15, and it will open to the public on May 16.

Fenix’s opening coincides with the rise of anti-immigration and far-right political rhetoric, which has deeply impacted minorities living in Europe and other Western countries, and increased hostility towards already marginalized people.

Although “Fenix is not a political museum”, as director Anne Kremers explained to Türkiye Today, its establishment and existence will aid the public in understanding what it means to be an immigrant.

She adds that "migration is an urgent topic and part of who we all are," and art is a powerful tool to tell personal stories, which can otherwise be hard to come across, digest, and understand.

Thus, Fenix aims to encourage everyone to reconsider migration as an experience that unites all humans instead of dividing them. Fenix presents migration as a common experience, as the only differences are the departure and arrival points.

It would be fair to say that non-Western cultures and histories have largely not been represented in museums, galleries, and other art venues. Their experiences have been explored through the Western lens and often romanticized or filtered to minimize the impact of colonization, imperialism, and exploitation in other forms.

Fenix is a museum where artists from diverse backgrounds have been encouraged to share personal experiences of migration and represent their communities.

I have had the privilege of visiting several world-renowned museums, and I could say that the representation of Turkish and Ottoman history in those exhibitions rarely made me feel seen. Neither the Ottoman Empire nor Türkiye’s history can be fairly reflected through carpets, ornaments, spices, and other objects. Turkish people have spread throughout the world, but their (hi)story has rarely been publicized.

Turkish migrants are part of the narrative at Fenix, where their personal stories and experiences help illuminate the impact of migration. The same is true for other communities that make up over half of Rotterdam’s population, including Moroccan, Surinamese, Indonesian, Cape Verdean, Dutch Caribbean, and other European and postcolonial groups.

Rather than offering a linear or nationalistic narrative of migration, the Fenix Museum presents movement as an emotional, spatial, and existential experience. Its exhibitions are structured as immersive installations rather than explanatory halls, using art, sensory architecture, and interactive storytelling to capture the complexity of migration not as a statistic, but as a human decision.

Visitors begin in the Suitcase Labyrinth, the emotional core of the museum. More than two thousand donated suitcases hold stories, letters, sounds, and objects from migrants across the world. These are not just symbolic props. They reflect the belief that personal memory, often dismissed as too subjective, is itself a valid historical source.

The visitors can listen to the personal stories of migrants from different historical and geographic contexts by using a little remote control to scan the label.

Many historians have proposed that oral accounts give voice to the silences in national archives and increase knowledge of marginalized communities' experiences. Personal (hi)stories, like the ones found in Fenix, reveal how cities like Rotterdam are remembered by those often excluded from dominant narratives.

Other exhibitions further cultivate this approach and make the experience of migration easier to understand and empathize with various means.

In the exhibition All Directions, visitors move through a maze-like space that reflects the fragmented and improvised routes migrants often take. With multiple pathways, dead ends, and no clear direction, the installation evokes the uncertainty and disorientation of real migration journeys.

The exhibition spans the first floor and features over 150 artworks and objects from the Fenix collection, alongside historical artifacts such as a UNHCR tent, a fragment of the Berlin Wall, and a 1923 Nansen passport for stateless people. Residents have also contributed personal items linked to their migration stories.

This installation also reflects what migration scholars describe as superdiversity, a condition shaped not only by ethnicity but also by class, gender, religion, education, and legal status.

As scholars Paul van de Laar and Peter Scholten proposed in 2023, Rotterdam no longer has a dominant majority. Instead, it is made up of many overlapping minorities, each with distinct journeys and reasons for arrival. The exhibitions do not try to flatten these stories into one voice. It presents their complexity as a lived urban reality.

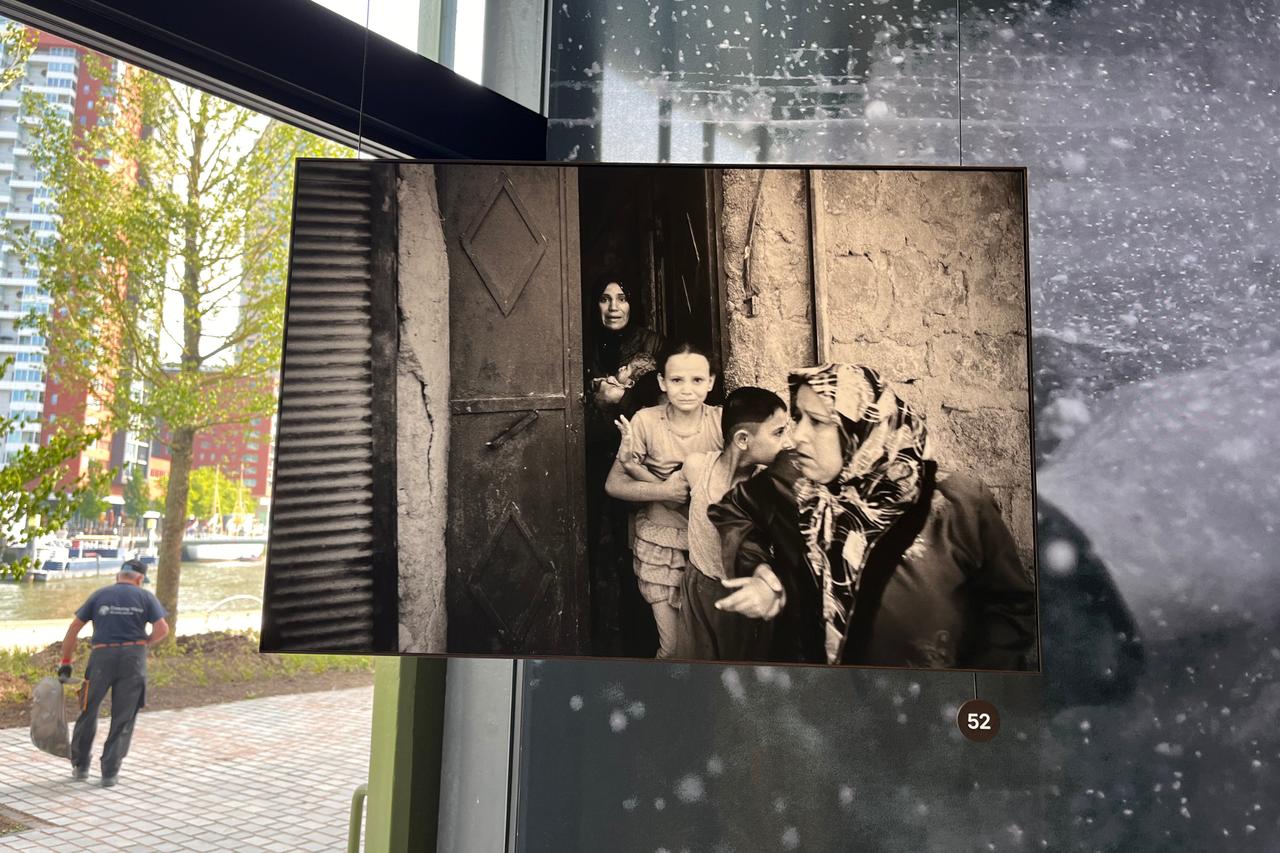

Perhaps the most politically charged space is the Family of Migrants, a room where visitors pass through enlarged family portraits from across decades and continents.

Unlike state museums, which often reduce migration to an abstract policy or national achievement, Fenix leans into the emotional weight of family separation, reunion, and memory. These images do not ask for pity or pride. They ask for recognition.

Many of the families shown in the exhibition reflect the people who live in Rotterdam today. Turkish and Moroccan workers arrived in the 1960s. Surinamese and Dutch Caribbean communities came after the end of colonial rule. Cape Verdean migrants found work through Rotterdam’s port.

These groups are not recent guests but part of the city’s foundation. Fenix makes clear that migration is not a crisis of the present, but a force that has shaped Rotterdam for generations.

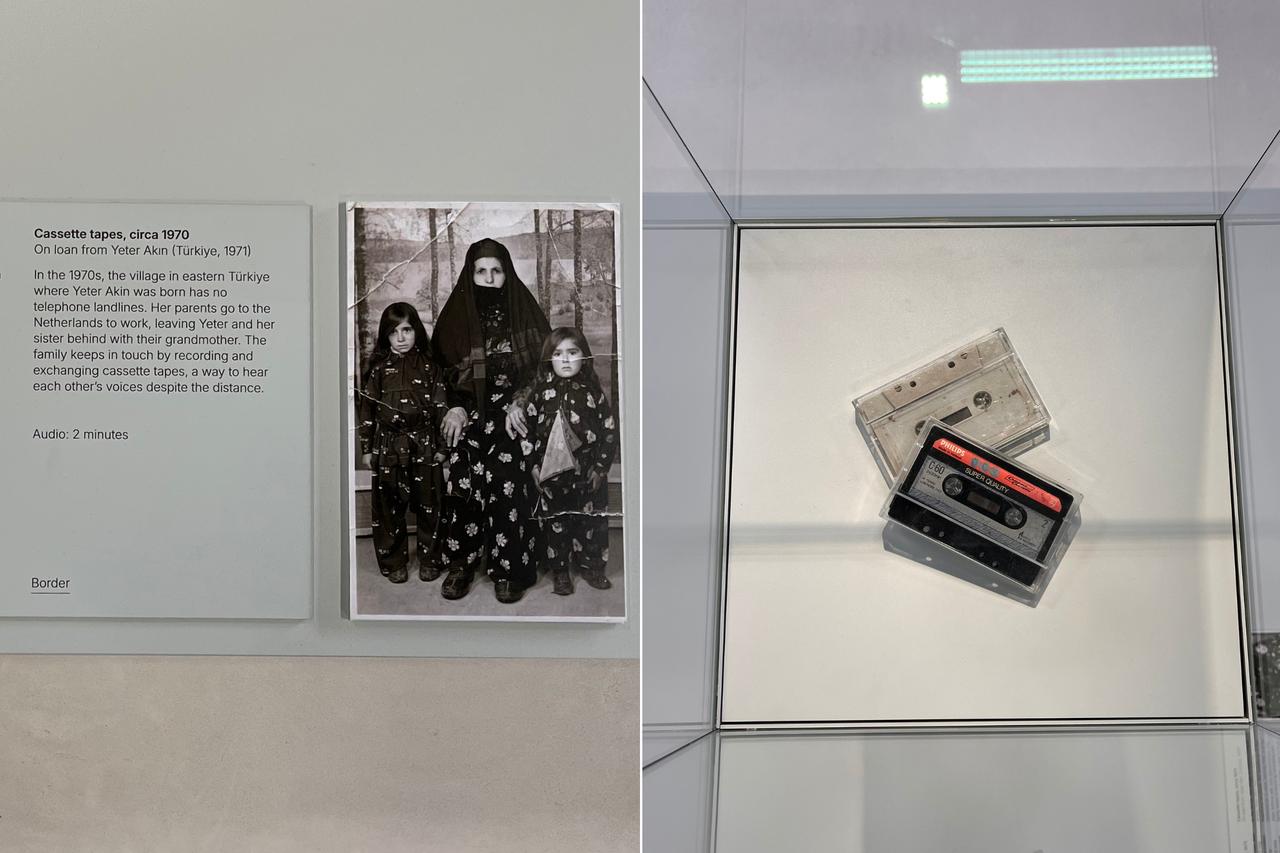

The arrival of Turkish workers in the Netherlands began with a bilateral labor agreement signed in 1964 between the Dutch and Turkish governments. As postwar reconstruction created major labor shortages, the Netherlands, like several Western European countries, turned to foreign workers to fill roles in low-wage, physically demanding sectors.

Turkish men, many from rural Anatolia, were recruited as "guest workers". The expectation was that their stay would be temporary. Most were single, living in boarding houses and working in factories, shipyards, or construction sites. Family reunification only began in the late 1970s and 1980s, when it became clear that many would not return.

Rotterdam became one of the main cities where Turkish migrants settled, due to its large port economy and constant demand for labor. In neighborhoods such as Charlois and Feijenoord, Turkish communities took root and began to shape local commerce, religious life, and education.

Over time, Turkish-owned shops, mosques, community centers, and associations helped establish strong social networks that continue to this day.

Despite their deep presence in the Netherlands, Turkish migrants have rarely been included in national history. The children of guest workers, born and raised in Dutch cities, often grew up in silence about their parents’ early years. Their stories were missing from schoolbooks and absent from public memory.

Many second-generation migrants did not learn about their family’s past due to the shame and anxiety tied to the condition of being an immigrant. Most discovered their roots only through informal conversations and shared memories within their families.

In my conversation with Fenix exhibition curator Selinay Sucu, she described the emotional complexity of collecting personal items from donors with migration backgrounds. She recalled visiting first- and second-generation immigrants who had long refused to speak about their past—but who opened up once they saw her.

Perhaps, she said, it was because they felt safe sharing their story with someone who understood and was there to listen. Their stories are now at the heart of Fenix.

Selinay’s own grandfather left Türkiye in the 1960s to work as a migrant laborer in the Netherlands, placing her within these histories. That personal connection came with an emotional toll, as each story she encountered carried its own heartbreak. Migration is a shared reality, but the experiences are always personal.

O Cafe and Bakery, located inside Fenix, is led by Turkish chef Maksut Askar, best known for his Michelin-star restaurant in Istanbul. At Fenix, he shares the culinary traditions of Anatolia through dishes passed down in families and adapted to everyday life. His menu features lentil soup, smoky eggplant, simit, borek, ayran, and breads made with ancient grains.

“O is a tribute to the migrants who brought their flavors, culinary heritage, and kitchen craft wherever they went,” Askar says. The name “O” - meaning he, she, it, or that in Turkish - reflects this inclusive spirit. “O speaks for everyone. Every person, every story, every identity.”

Just beside the cafe is the Plein, an open indoor square measuring more than two thousand square meters. Free to enter and designed for public use, it hosts performances, community events, and casual gatherings throughout the year.

“Migration stories are the heartbeat of Fenix,” museum director Anne Kremers says. “We have woven them into every element, whether it is the architecture, the artworks, the freely accessible Plein, or the gelateria by the Granucci family. We want everyone to feel welcome.”

Support for Palestinians is far from guaranteed in the Netherlands and other European countries. While activists, artists, and civil society organizations have long called attention to the violence and displacement caused by the Israeli occupation, public institutions have often remained silent or neutral. In this context, it is notable that Fenix includes a work by Palestinian photographer Rula Halawani in its permanent exhibition.

However, it is only one photograph. Taken at the Qalandia checkpoint in 2004, the image is part of Halawani’s series “Intimacy”, which documents the tension, repetition, and erasure involved in crossing the heavily controlled border between East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

The photo is powerful, but its solitary presence raises questions. In a country where Palestinian flags have been banned from some protests and where public language around the conflicts is carefully coded, including even one image can be considered an act of visibility. Yet in a museum that celebrates global migration stories, the fact that Palestine is represented by a single checkpoint photo from two decades ago is also a significant detail.

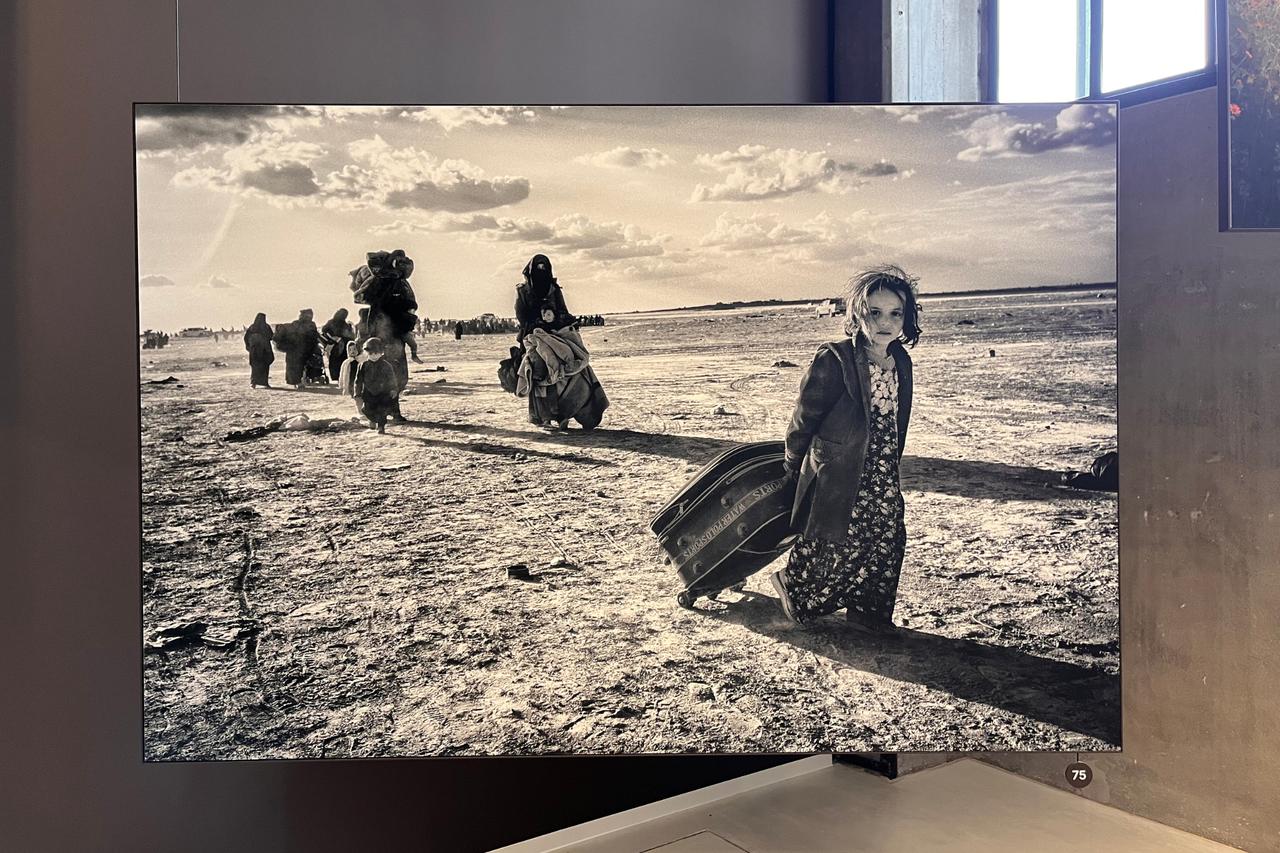

In contrast, Syrian experiences are more fully integrated into the Family of Migrants exhibition. Since the war began in 2011, the Syrian people have been widely associated with the term refugee.

At Fenix, they are shown not as a crisis but as part of a longer story of displacement. The exhibition includes photographs and stories that speak to loss, survival, and the rebuilding of life in unfamiliar places. These accounts sit alongside others, not separated by nationality but connected through shared vulnerability.

Visitors entering Fenix are immediately drawn upward. Rising through the heart of the museum is the Tornado, a twisting double staircase that climbs from the ground floor to a rooftop platform with sweeping views of the Maas River and the Rotterdam skyline. The structure does not follow traditional museum architecture. It evokes motion, tension, and transformation. The same forces that define migration itself.

Droom en Daad Foundation director Wim Pijbes recalled his conversation with MAD Architects founder Ma Yansong after giving him a tour of the warehouse and sharing his vision about making the Fenix museum.

Ma Yansong's immediate reaction was that what this museum needed was a structure that reflected "movement", which became its essence.

Designed by MAD Architects, a Beijing-based studio, the Tornado is both sculpture and structure. It is the first museum designed by a Chinese firm in Europe, an intentional choice in a neighborhood that was once home to mainland Europe’s earliest Chinatown.

The Tornado is built on top of a former shipping warehouse, a place where people and goods once departed by sea. Now, this swirling steel form invites visitors to look outward again, but from a new perspective.

Unlike grand staircases that convey power or stability, the Tornado moves. Its shape echoes rising air, but also uncertainty. There is no single path, only a spiral of steps that mirror the non-linear journeys taken by migrants, refugees, and travelers. It is not just a way to reach the roof.

Tornado facts

Andrea D’Antrassi, associate partner at MAD Architects and project lead for Fenix, spoke to Türkiye Today about the meaning behind the Tornado. When I shared my observation that the structure represents chaos within order, much like in nature, he agreed and explained that this was exactly the idea.

The inspiration comes from the natural tornado: a phenomenon that looks chaotic but follows an internal logic. The design of the Tornado is complex and chaotic, but the engineering of the structure had to be perfect to hold it up, which seems to be the perfect metaphor for Fenix.

Each of the twelve thousand five hundred unique wooden planks, each step in the spiral, leads the visitor into a tornado of memories, emotions, and lived experiences. It is a physical expression of the personal journeys the museum exists to honour.

Fenix owes its existence to the Droom en Daad Foundation, a Rotterdam-based cultural initiative founded in 2016. Led by art historian Wim Pijbes, the foundation focuses on creating cultural projects that enrich the city while remaining in the background.

Their aim is not to draw attention to themselves, but to let the art speak for itself. This philosophy is evident as the foundation will not take the stage at the opening of Fenix, just as they chose not to speak during the inauguration of Thomas J. Price's "Moments Contained" statue at Rotterdam Central Station in 2023.

As Wim explained, they intend to highlight the art, not the foundation behind it, which is why they prefer to follow the events as part of the crowd.

Although Droom en Daad's projects are deeply rooted in Rotterdam, the foundation’s goal is to create cultural venues that resonate both locally and internationally. They want Rotterdam to be a center of art that not only educates its residents but also attracts visitors from around the world.

This approach is exemplified by initiatives like the new photography gallery and plans for public dance venues. As Wim noted, art can address complex themes and communicate in ways that words cannot, making it a powerful medium for fostering understanding and empathy.

The foundation also embraces the role of philanthropy in societal development. Wim emphasized that their economic stability "allows them to take risks," explore innovative projects, and "make mistakes". They see this as a responsibility to push boundaries and create spaces where art can thrive and connect people in ways traditional methods cannot.

Fenix stands on the south bank of the River Maas, in Katendrecht, a district shaped by over a century of migration. The museum occupies part of the former San Francisco Warehouse, once the largest transshipment warehouse in the world.

From the late 19th century, millions of emigrants boarded ships from these quays, heading toward North America. Among them were figures like Albert Einstein and Willem de Kooning. Across the water stands Hotel New York, the former headquarters of the Holland America Line, visible from Fenix’s upper floors—a reminder of the journeys that shaped Rotterdam.

Katendrecht was also a place of arrival. Cape Verdean sailors, Surinamese musicians, and one of mainland Europe’s first Chinatowns made this peninsula home. The museum’s tornado-shaped tower, designed by Chinese studio MAD Architects, nods to that history while imagining new futures.

The area was not spared in World War II. After bombings and fire, the original warehouse was rebuilt in 1950 by many of the same migrant communities who had once worked there. It was split into Fenix I and Fenix II, the latter now home to the museum.

For decades, Katendrecht remained isolated from the city’s north, known as a rough working-class area. That began to change with the construction of a bridge connecting the peninsula to the center. Today, it is undergoing large-scale redevelopment, including a future city park in Rijnhaven and the upcoming National Museum of Photography.

Nonetheless, Fenix is rooted in a site of both departure and arrival, reminding visitors that this transformation is built on layers of memory, shaped by those who left and those who stayed.