The remains of people who lived nearly 12,000 years ago at Cayonu Hill in southeastern Türkiye are being studied to map one of the earliest known human communities, offering fresh insight into how agriculture, settlement, and long-distance social ties first took shape.

Located in the Ergani district of Diyarbakir province, near the Tigris River, Cayonu Hill is widely regarded as one of the key sites marking humanity’s shift from nomadic hunting and gathering to permanent village life and food production.

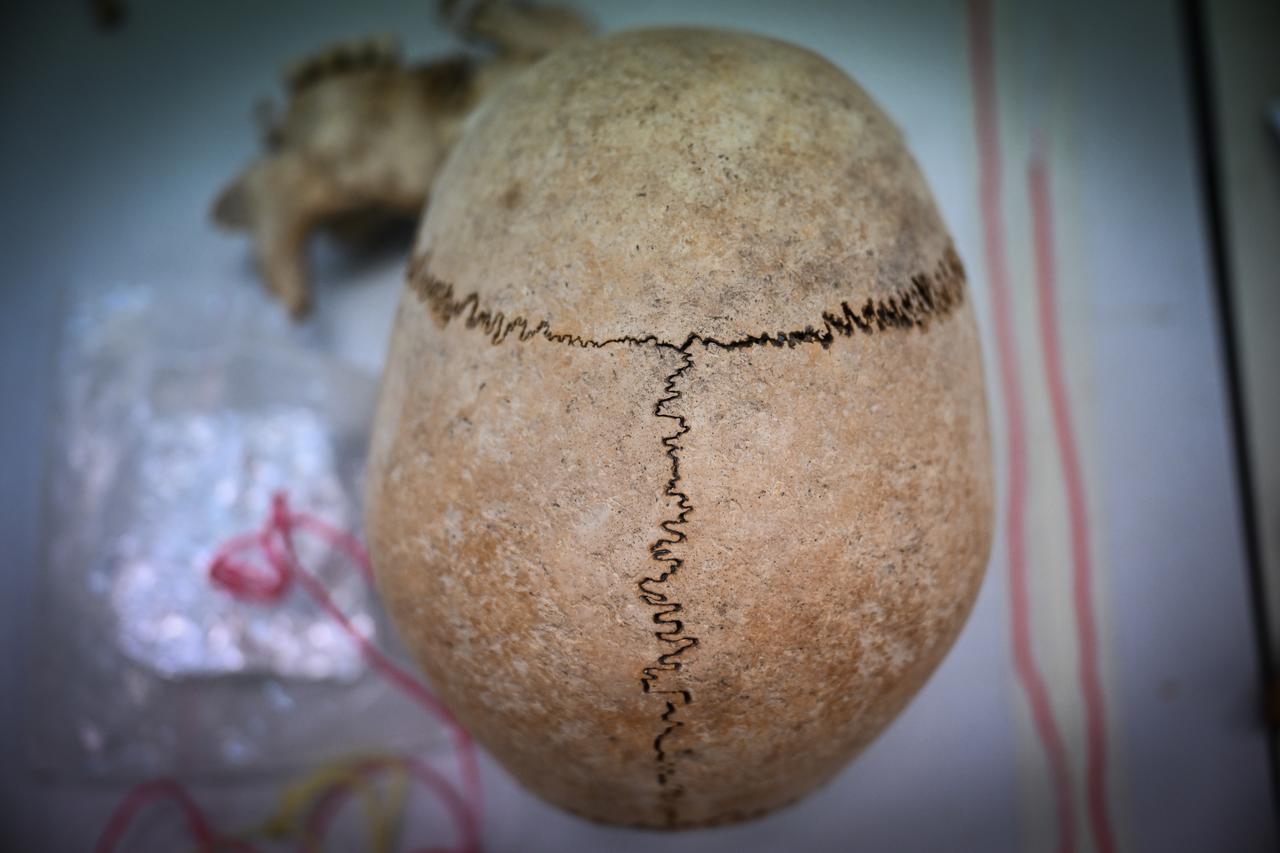

Bones uncovered during ongoing excavations are now being examined at Hacettepe University, where researchers are reconstructing the genetic and social profiles of the community that once lived there.

Cayonu Hill was first identified in the early 1960s and excavated shortly afterward by pioneering archaeologists Halet Cambel and Robert J. Braidwood. Since then, the site has become central to international research on the Neolithic period, a term used for the era when humans began farming and building permanent settlements.

After a long pause due to security concerns, excavations resumed about a decade ago under the authorization of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The current project is led by Assoc. Prof. Savas Sarialtun of Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, with Prof. Omur Dilek Erdal from Hacettepe University, coordinating the anthropological research.

Recent fieldwork has uncovered architectural layers spanning several thousand years, including grid-planned buildings from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, a phase when communities built permanent houses before the widespread use of pottery.

Archaeologists have also identified a public building thought to have hosted gatherings or communal activities.

Later layers reveal dense architectural remains from the Pottery Neolithic era, as well as a water channel and burial areas dating to the Early Bronze Age. According to the excavation team, these findings point to uninterrupted occupation and a highly organized settlement structure.

Eight graves excavated during the most recent season have added depth to the picture of daily life and social organization. Most of the burials date back to around 3,000 B.C., while one belongs to the much earlier Neolithic period.

Grave goods such as pottery, copper and bronze objects, tools, and daggers were found alongside the deceased. Seals discovered near the burial area suggest that trade networks and forms of social distinction were already taking shape, indicating links between Cayonu Hill and surrounding regions.

Beyond archaeology, genetic analysis is playing a key role in the research. Sarialtun explained that DNA data are being used to map how the community connected with regions such as Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, and Anatolia, revealing long-distance interaction networks that existed thousands of years ago.

These studies, which began intensively in 2024, are expected to take several years, with researchers planning to share comprehensive results with the public in the coming period.

At Hacettepe University, Prof. Erdal and her team have so far analyzed the remains of around 255 individuals from Cayonu Hill. She described the population as highly diverse, with clear evidence of cultural variation and interaction with neighboring groups.

Despite this diversity, skeletal evidence suggests a largely peaceful community with shared workloads. Men and women appear to have taken on different but complementary roles, while even children show signs of early involvement in agricultural and daily tasks.

The uniform design of houses across generations also points to some form of collective planning or governance, even though sharp social hierarchies are not clearly visible in the remains.

Taken together, the archaeological and genetic findings from Cayonu Hill are helping scholars piece together how some of the world’s first settled communities lived, worked, and connected with others.

As analysis continues, the site is expected to remain a cornerstone for understanding the deep roots of modern society.