Dramatic and sensational claims about archaeological sites in Türkiye—ranging from secret ancient gospels and vanished workers in Tarsus to alien portals at Gobeklitepe and the infamous “Gate of Hell or Pluto's Gate” at Hierapolis—have captured global attention. Yet, careful scientific study and meticulous excavations reveal that many of these stories either lack solid evidence or have natural explanations, demonstrating the importance of rigorous research in distinguishing myth from reality.

As an archaeologist who has worked extensively in Türkiye for many years, I approach these sensational claims with a critical and informed perspective. Drawing on firsthand experience and scientific methods, I aim to separate fact from fiction and shed light on what the evidence truly reveals about these fascinating archaeological sites.

A period of intense media attention centered on an excavation under a modest house in Tarsus, a coastal town in Mersin province that is historically linked to St. Paulus (Paul the Apostle). Sensational reports claimed an untouched gospel, a vast hoard of gold, secret tunnels and even the disappearance of workers, and these stories quickly took on a life of their own.

According to one dramatic account that circulated in the press, anonymous participants claimed that “phones cut out there” and recounted a story of a 15-person dig team that entered and never reappeared. That account was presented as a first-hand witness claim, but later checks did not substantiate the most extreme allegations.

In fact, the excavation on a shanty in the 82 Evler neighbourhood was carried out under high-level oversight and concluded without producing evidence for those grand claims. State security units supervised the operation, which began on Nov. 13, 2016, and ended on Nov. 3, 2017.

An expert report dated Nov. 2, 2017, recorded only a modest set of finds: one bronze coin, a broken column fragment and ceramic pieces that were evaluated for study, and did not list any inventory-level movable or immovable cultural property beyond these items. The homeowner denied that anything extraordinary had happened at the property, and there was no official missing-persons report to back the tales of disappeared workers.

By the way, the dig took place in a third-degree protected archaeological zone—a legal designation in Türkiye that restricts construction and protects heritage—and the formal documentation and handover followed accepted procedures.

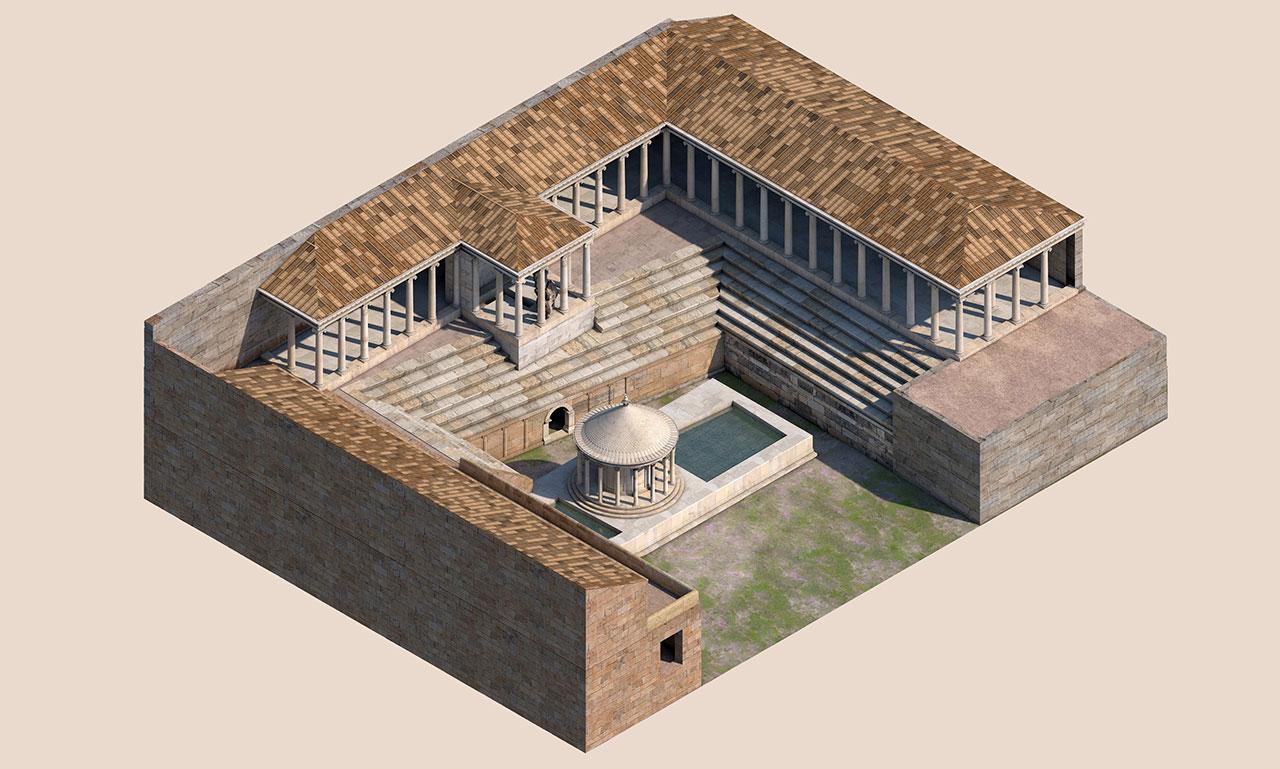

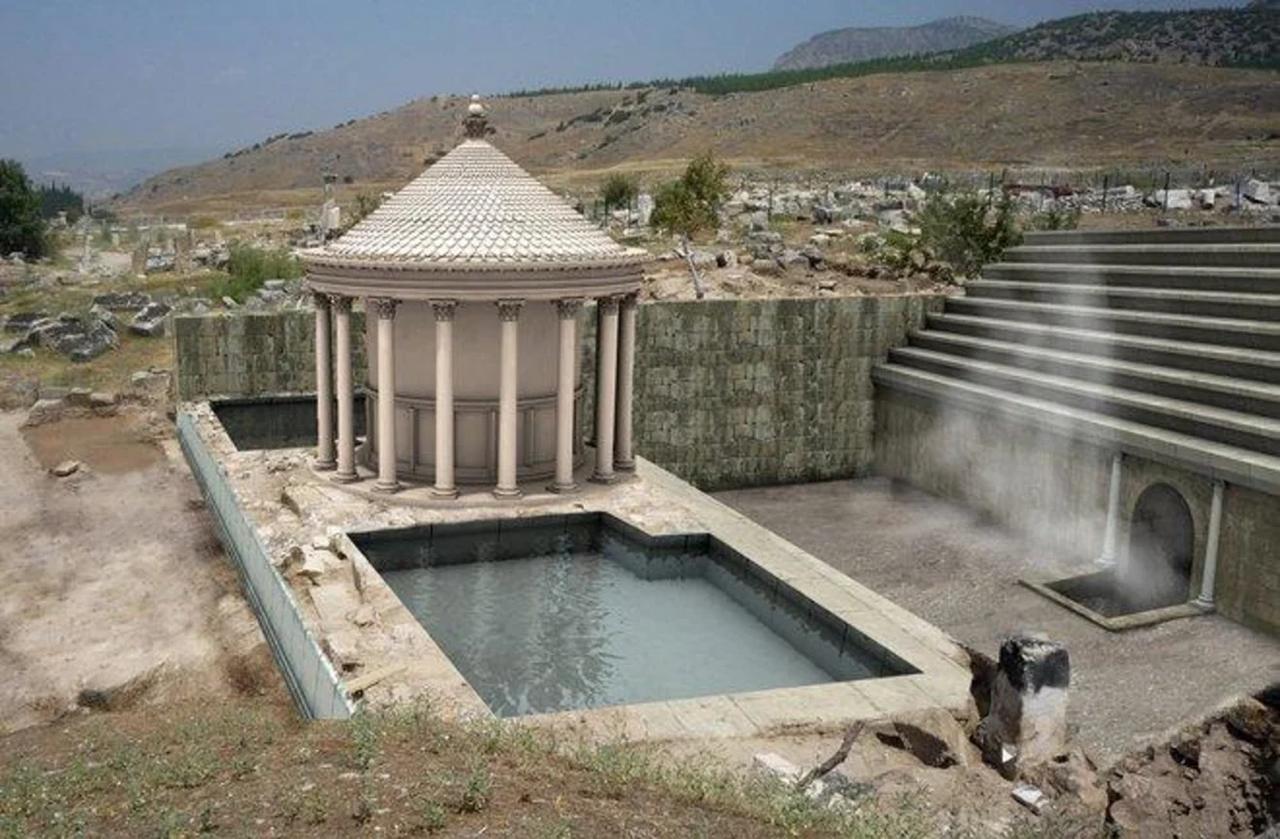

Hierapolis, the Roman spa city that sits above Pamukkale’s white travertine terraces, supplied some of the region’s most enduring stories. Ancient writers described a ritual theatre in which animals introduced into a certain pit died instantly, while priests apparently left unharmed, a spectacle chronicled by observers like the Roman author Pliny and the geographer Strabon.

Strabon conveyed his astonishment in vivid terms: “I threw sparrows into it; they immediately gave their last breaths and fell to the ground.” That dramatic image carried through the ages and became the basis for the site’s popular label, the “Gate of Hell or Pluto's Gate.”

Modern scientists set out to test whether a natural cause could explain the phenomenon. Volcanic and tectonic processes in the region release gases from deep underground, and a geobiologist, Hardy Pfanz, measured the air around the so-called Ploutonion or Plutonium (the ancient pit associated with Hades) with portable equipment. He reported levels of carbon dioxide that were strikingly high compared with normal air—where carbon dioxide stands at about 0.04% by volume. Pfanz noted readings that approached the order of magnitude of tens of percent, and he warned that “just a few minutes of exposure to 10 percent carbon dioxide can create a life-threatening situation. The levels here were truly lethal.”

Those measurements provide a direct, natural explanation for why small animals would quickly die at ground level while taller humans, breathing higher in the air column, could survive and reappear, which in turn helps explain the ancient eyewitness reports and ritual practice.

Scientists also found that gas concentrations shift with temperature and atmospheric conditions. During warm, sunny hours, carbon dioxide disperses more readily; during cooler nights, it settles toward the ground, forming a dense layer that can act like a dangerous, localized “gas lake.” That pattern helps account for why the phenomenon might have been observed episodically and why priests of the ancient cult might have been able to survive while animals did not.

Today, the affected area is fenced and bricked, with viewing platforms and walkways that let visitors look down on the small rectangular pool without entering the hazardous zone.

Gobeklitepe in the Sanliurfa region has become a focal point for both mainstream archaeology and speculative theories. The site draws large numbers of visitors and has become a magnet for alternative narratives, with some visitors or authors proposing ideas ranging from alien builders to ancient observatories or portals.

Graham Hancock, who promotes controversial reconstructions of prehistory, has connected Gobeklitepe to early astronomical knowledge and apocalyptic scenarios, and other researchers have advanced astronomical interpretations of particular carvings and pillars.

A study by two University of Edinburgh researchers suggested that carvings, notably on a T-shaped Pillar 43, could depict a catastrophic meteor event some 12,000 years ago, tying the imagery to the so-called Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis.

That claim sparked debate. Some excavators, including Jens Notroff and colleagues, cautioned that such readings oversimplify the material and that recent work points toward more nuanced functions for those elements. Notroff and others have argued that the round structures in Gobeklitepe’s third layer were very likely roofed and then deliberately buried, a sequence that makes it unlikely they served as open-air observatories for star-watching.

Local site directors underline a social and cultural reading of the imagery. Professor Necmi Karul, head of excavations at Gobeklitepe and Karahantepe, framed the carved scenes as “expressions of known stories from the past, which hold an important place in the construction of a new social order.”

His view is that the monumental pillars and their decoration were part of a symbolic program of memory and identity-making rather than a technical astronomical installation. In short, while Gobeklitepe clearly stands out as a place of complex meaning and extraordinary workmanship, the assertion that it functioned primarily as an observatory or as a portal is not supported by the full range of archaeological evidence to date.