An eye-opening academic study sheds light on how archaeology was systematically employed in Nazi Germany to reinforce ideology, racial theory, and militarism. Drawing on 19th-century German thought and philosophies of national identity, the regime used archaeological findings to fabricate narratives of ethnic purity and justify the occupation of foreign lands.

The scholarly analysis published in the Journal of Archaeological Research on January 2025, highlights the sinister relationship between archaeology and Nazi ideology.

The research examines how the Nazi regime strategically manipulated archaeological findings to justify its brutal expansionism and racist worldview. This misuse of science not only reinforced the myth of Aryan supremacy but also laid intellectual groundwork for crimes against humanity.

At the heart of Nazi archaeological thought was the concept of Nordicism — the belief in the inherent superiority of the so-called Nordic race. Influenced by 19th-century pan-Germanism and the romantic writings of thinkers like Johann Gottfried Herder, Nazi ideologues used archaeology to promote an imagined pure lineage stretching back to mythical Germanic ancestors.

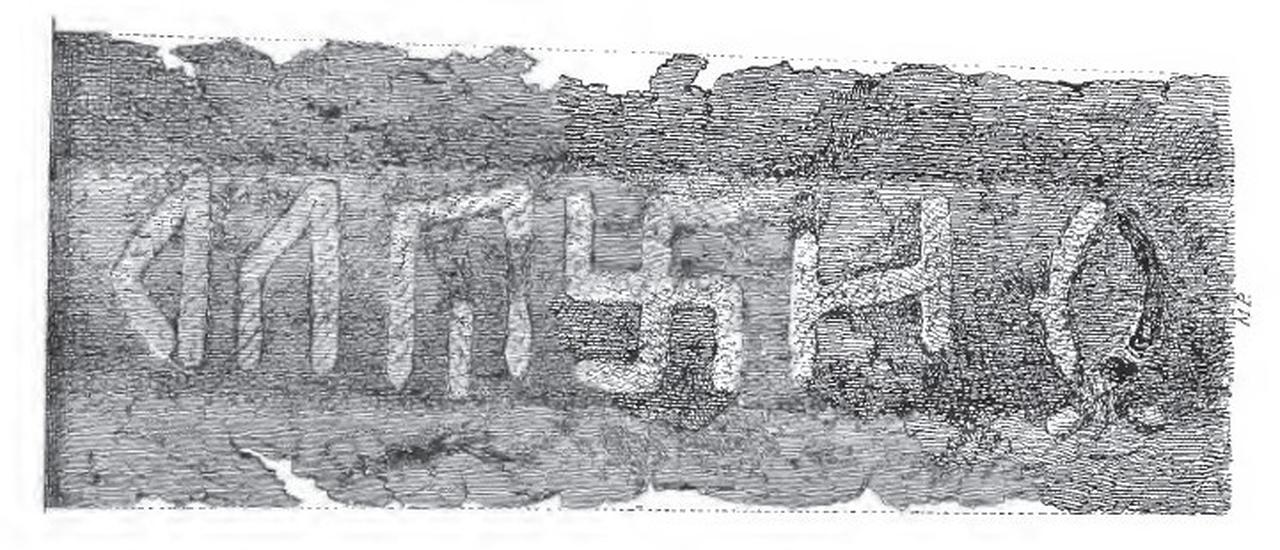

Key scholars such as Gustaf Kossinna and Oswald Menghin claimed they could trace German roots through ceramic fragments and burial sites. Their work fuelled a narrative that present-day Germans were direct descendants of a noble prehistoric Nordic people — and that these ancestors once ruled vast territories from Scandinavia to Eastern Europe.

This constructed heritage was not just academic fantasy; it served practical political ends. For instance, when Nazi forces invaded Poland in 1939, leading archaeologists like Hans Reinerth published articles arguing that regions like the Vistula River basin were ancient German homelands.

Ceramic artefacts and settlement traces were twisted into “evidence” that Germanic tribes had always inhabited these lands — thus, modern military conquest was framed as a patriotic act of reclamation.

Such pseudo-historical arguments legitimised the violent displacement of millions and the destruction of entire communities, as archaeological rhetoric blurred into aggressive propaganda.

Under the Third Reich, institutions such as the notorious Ahnenerbe and the Nazi Party’s archaeological department flourished. Funded by the state and protected by high-ranking Nazis like Heinrich Himmler, these organisations conducted excavations across occupied Europe.

In France, Poland and other occupied territories, archaeologists supported by soldiers and forced labour dug up graves, temples and settlements — always looking to prove Germanic or Nordic primacy. Even sacred sites were repurposed into nationalistic exhibits to shape public sentiment and recruit support for Nazi goals.

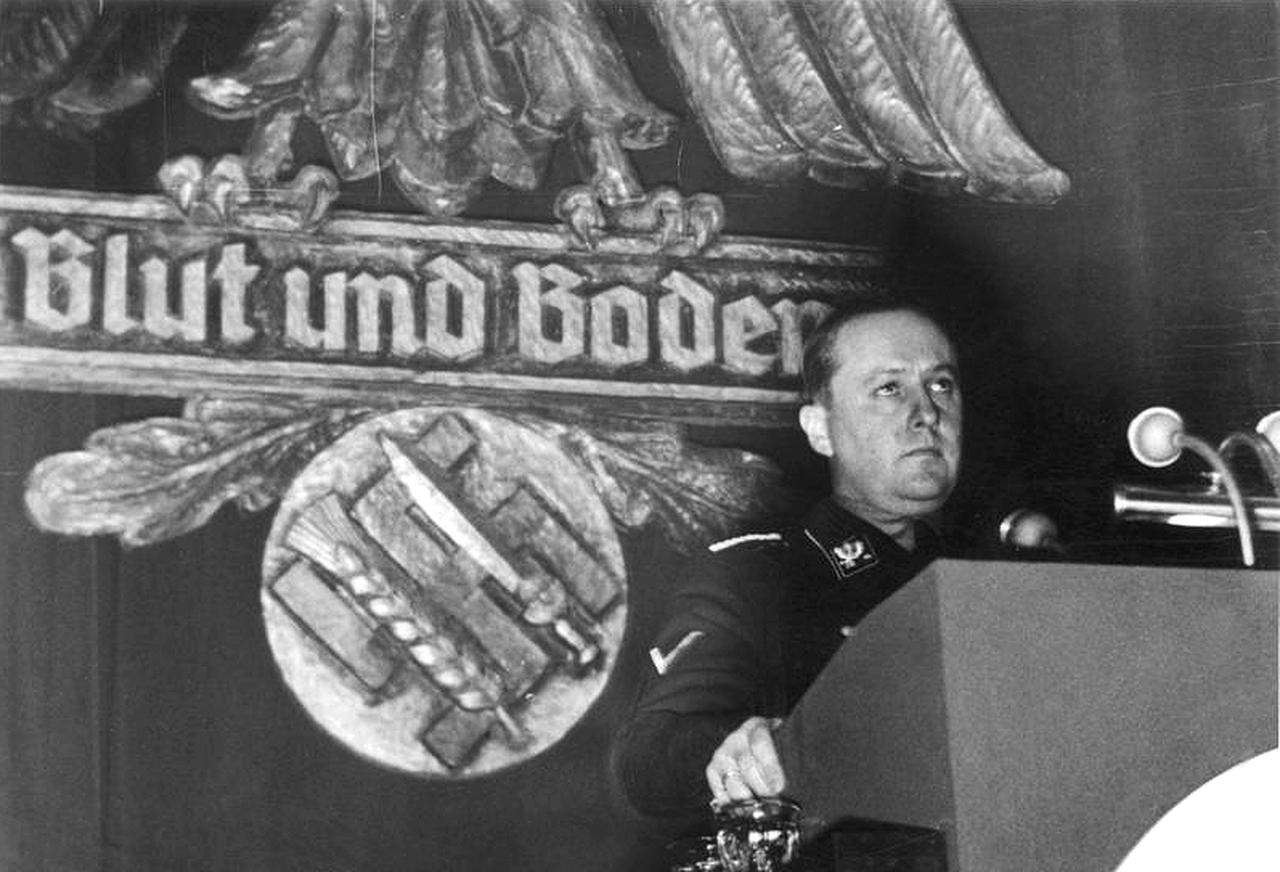

One of the most insidious outcomes of Nazi archaeology was the popularisation of the Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil) doctrine. This ideology fused ethnicity with territory: it claimed that a true German could only flourish in the ancestral homeland and that racial purity must be preserved through strict social policies.

Under this myth, foreign populations and minorities — especially Jews and Roma — were demonised as pollutants of both blood and soil. This provided pseudo-scientific backing for anti-Semitic laws, forced sterilisation and ultimately genocide.

Although not central to Nazi ideology, archaeology played a vital supporting role. The study warns of the dangers of allowing ideology to distort scholarly research, especially in an age where archaeogenetics and migration studies can be misused for political agendas.

The Nazi case illustrates how a blend of intellectual traditions, selective science, and authoritarian power can produce a deeply damaging misuse of the past.