Archaeological excavations in Demre, Antalya, are steadily closing in on the long-debated burial place of Saint Nicholas of Myra, the fourth-century bishop who inspired the modern-day figure of Santa Claus, as researchers link an ancient floor and a buried limestone sarcophagus to the same sacred landscape.

In the coastal district of Demre in Antalya, the St. Nicholas Church stands over the remains of an earlier, fourth-century church where the bishop served and died. The current building, constructed around 520 on top of this older structure, turned the small town of Myra into a major Christian pilgrimage center after the bishop’s death in the mid-fourth century, and it has carried that role into the present.

Archaeological excavations that began in the late 20th century revealed the foundations and floor of the earliest church, which had been buried under layers of sand and silt. Spoke to Turkish media in 2022, the head of the Antalya Regional Board for the Protection of Cultural Assets, Osman Eravsar, said that recent work has exposed the level where Saint Nicholas would have walked and prayed, and he described this as “a very important discovery, the first find belonging to that period,” since it ties the living space of the bishop directly to the surviving architecture.

Researchers have focused on a domed, three-apsed section of the church, an area with three semicircular recesses at the eastern end, which has long been seen as the most prestigious part of a Byzantine sanctuary. During excavations here, they documented a fresco showing Christ holding a Gospel book in his left hand and making a gesture of blessing with his right, and Eravsar indicated that this image stands just above the place where the saint’s coffin was originally set down.

A marble floor tile bearing the Greek word charis, meaning “grace,” may indicate the exact spot of the original grave, and the overall design of the church appears to echo the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, which commemorates the crucifixion and resurrection of Prophet Jesus.

Just as the Jerusalem church has an unfinished dome over the central shrine, the dome of the St. Nicholas Church in Myra was never fully completed, even when it was restored in the 1860s on the orders of Russian Emperor Alexander II, and this unfinished feature has been interpreted as a deliberate way to link the Anatolian site to the story told in Jerusalem.

In 2022, William Caraher, an archaeologist of early Christian architecture who was not involved in the excavations, noted that it is common for churches to be built on top of earlier sanctuaries and that the presence of an older structure underneath often encouraged later construction. At the same time, he pointed out that the marble tile with the Greek inscription may have been reused from another context, since the word charis was widely employed in antiquity, and he therefore treated the tile as a suggestive but not decisive clue.

The life of Saint Nicholas remains only partly known, yet legends have grown up around him. Medieval stories say that he rescued three daughters from forced prostitution, cut down a tree believed to be possessed by the devil, brought three children back to life and even exchanged blows during the First Council of Nicaea in 325, while also giving away his inherited wealth anonymously to people in need, which later fed into the Santa Claus tradition.

Over time his burial place became a target. A Latin manuscript translated by late medieval specialist Charles W. Jones describes how, in 1087/1089, a group of “wise and famous men” from Bari in Southern Italy discussed how they might remove Santa’s body from the city of Myra. According to this account, they planned to break through the church floor, succeeded in taking most of the skeletal remains and carried them off to Bari, leaving only a few bones and a damaged stone coffin, or sarcophagus, behind in Demre.

In the annexes of the same church complex, a separate excavation has opened up a new line of inquiry. Since 1989, archaeologists have been digging in a two-storey extension of the St. Nicholas Church, and within this structure they have uncovered a limestone sarcophagus, which is a stone coffin commonly used in antiquity.

The work forms part of the “Heritage for the Future" project run by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, and is led by Associate Professor Ebru Fatma Findik of Hatay Mustafa Kemal University. She has explained that the sarcophagus is made from local limestone, measures about two meters in length and has a pitched, roof-like lid that fits the patterns seen in other examples from the region. Before they identified the coffin itself, the team found animal bones and many broken clay lamps, which encouraged them to see the space as a burial area linked to rituals of commemoration.

For Findik and her colleagues, the most urgent task now is to uncover any inscriptions on or around the coffin that might reveal when it was made and who was placed inside it. She said that “our biggest hope is to find an inscription on the sarcophagus,” because such a text could clarify the contents of the burial and help the team date it more precisely. At present only part of the burial chamber has been opened, and the archaeologists plan to continue to dig down in order to expose more of the structure.

Birol Incecikoz, Director General of Cultural Assets and Museums in Türkiye, told the daily Hurriyet in 2024 that scientific analysis will play a decisive role in determining whether the sarcophagus could belong to Saint Nicholas himself. He said that the location fits historical descriptions and that the team is “not yet at the point of declaring this as the tomb of Saint Nicholas, but we are getting closer,” adding that carbon testing and other laboratory procedures are under way to test the authenticity of the find. The lid of the coffin matches the period in question, although only detailed study of the bones inside can show whether they come from the bishop who lived during the Roman Empire.

A fragment of his bones is already preserved in the Antalya Museum, and some historical sources have suggested that not all of his remains travelled to Bari, leaving open the possibility that a portion stayed in what is now southern Türkiye.

According to accounts from late antiquity and the Middle Ages, Nicholas was born in the late third century in Patara, a thriving city of the Lycian civilization, and later became bishop of Myra, corresponding to modern Demre. He gained a reputation for helping the poor, especially girls who were unable to marry because their families could not provide a dowry, and he was said to leave money secretly in their homes at night so that they would not be shamed.

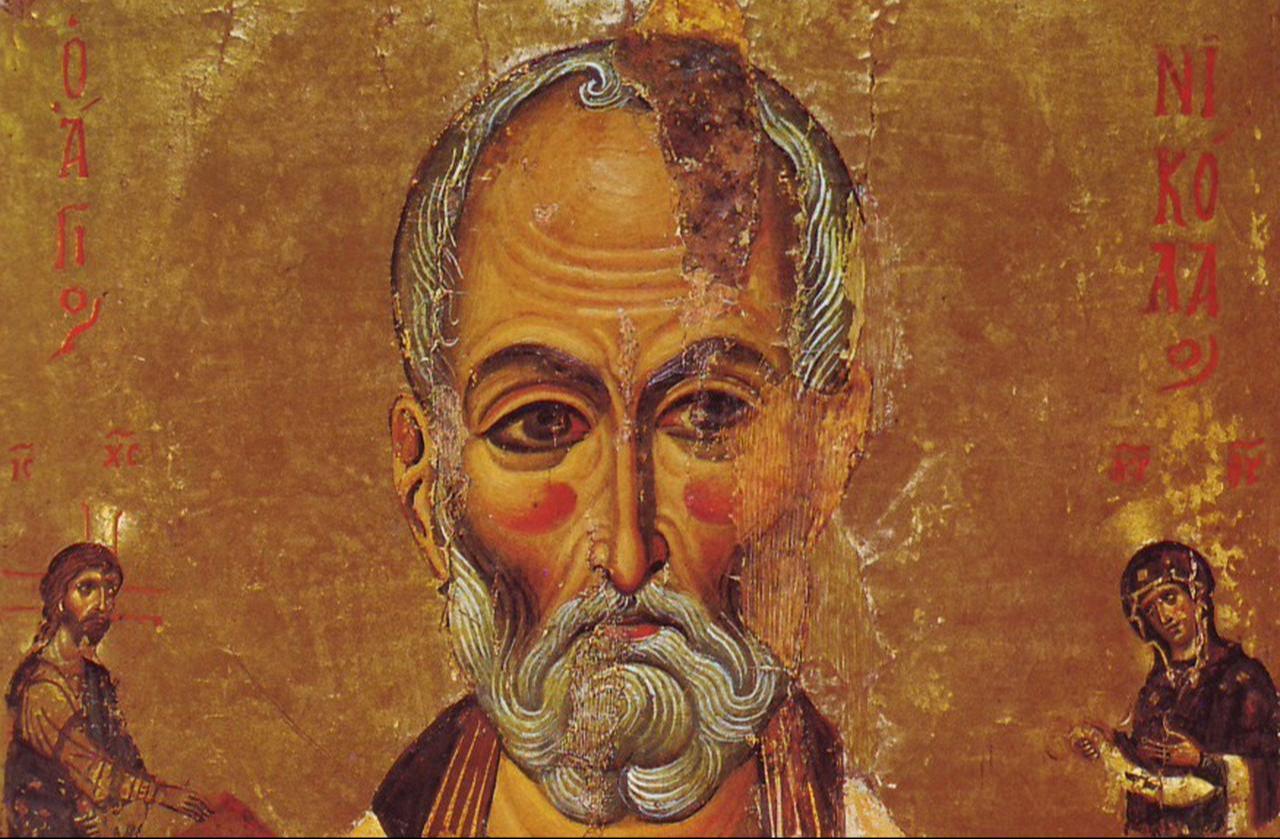

Professor Ekrem Bugra Ekinci has noted that icons often show Nicholas holding three golden balls, and that the custom of hanging stockings by the fireplace so that Santa can drop in gifts goes back to this part of the story. Other traditions say that he calmed a storm on a voyage to Jerusalem, which led sailors to adopt him as a protector, and that he was imprisoned for spreading the teachings of Jesus before dying in 342.

The saint’s reputation spread widely. He became one of the most popular holy figures in Europe and in the former Russian Empire, and he was venerated in places such as Freiburg in Germany, Bari and Naples in Italy and across the island of Sicily. In Dutch and English his name turned into “Santa Claus,” and in this form he eventually came to be seen as one of the protecting figures of New York.

He was regarded as a righteous believer by Muslims because he lived before the time of Prophet Muhammad.

Over the centuries, the figure of Saint Nicholas gradually merged with local customs and myths in northern Europe. The Dutch called him “Sint-Nicolaas,” a name that evolved into “Sinterklass” and eventually “Santa Claus,” and Dutch migrants carried this tradition with them when they sailed to America, even placing a bust of the Nicholas on the prow of one of the first ships. One of the earliest churches in the United States was also dedicated to him, which helped to fix his image in the new world.

Writers and artists then built up the modern picture of Santa. In a children’s poem, William Gilley portrayed St. Nicholas as Santa Claus riding in a flying sleigh drawn by eight reindeer, a scene that echoes Norse tales in which the Odin comes down to earth each December on an eight-legged horse named Sleipnir to help the poor, and similar patterns appear in Roman and German legends. In 1837, the book The Book of Christmas by Hervey helped to spread the story, and between 1863 and 1866, the illustrator Thomas Nast drew images of Santa for Harper’s Weekly, dressing him in a red suit with a white beard and a sleigh pulled by reindeer. These drawings were requested by President Abraham Lincoln in order to boost the morale of soldiers during the American Civil War.

In the 20th century, commercial art fixed the image further. In 1924, Swedish-American artist Haddon Sundblom adapted Nast’s caricature for a Coca-Cola advertising campaign, which, according to Ekinci, allowed the drink, once banned from advertising to children because of its early ingredients, to appeal to younger audiences. In 1939, a department store in Chicago circulated 2.5 million copies of a promotional booklet that portrayed Santa in a similar outfit, and this visual model spread quickly through mass media.

The St. Nicholas Church in Demre was placed on UNESCO’s Tentative Heritage List in 2000, which underlined its status as a significant historical and cultural monument. The building, with its Middle Byzantine architectural style and rich decoration, has often been described as one of the most distinguished examples of its period, and it continues to draw large numbers of visitors every year, especially from Russia.

Across the wider Mediterranean, churches and chapels dedicated to St. Nicholas can still be found in both Orthodox and Catholic traditions, and the Demre church remains central to that network. As excavations continue around its foundations and annexes, and as carbon tests proceed on the newly uncovered coffin, archaeologists alike are watching to see whether the soil of southern Türkiye will finally yield firm evidence for the last resting place of the man behind Santa Claus.