The documentary One More Show premiered on Thursday within the Gala section of the 46th Cairo International Film Festival, documenting how the “Free Gaza Circus” continued performing for children during the war and offering a look at daily survival and the persistence of joy amid destruction—a portrayal that echoes Albert Camus’ idea of resisting absurdity through human action.

The film, directed by Mai Saad and Ahmed al-Danaf, follows a group of young Palestinians who refused to surrender to the reality of war and decided to keep the circus alive as a space for joy and rescuing what remains of childhood in shelters and displacement schools.

The film follows five young Palestinians who lost their homes and training center after an airstrike targeted the “Free Gaza Circus,” which was founded in 2018.

Despite that, they refused to stop and continued delivering mobile performances in displacement shelters and schools while the sound of the drone—an Israeli reconnaissance aircraft—hummed in the background as if it were a fixed part of the air.

Alongside its human significance, One More Show offers a philosophical reading of what it means to hold on to life in a reality that lacks logic.

The scene depicting children laughing and interacting with the performances of the “Free Gaza Circus” is not a temporary reclamation of a violated childhood; it represents—at its core—what Albert Camus described as “rebellion against absurdity.”

Camus's concept refers to the insistence on human action despite the absence of meaning in an environment where death dominates the horizon.

According to Camus, absurdity arises from the collision between the human desire for a meaningful life and a reality that defies interpretation—a reality governed by violent force rather than logic.

In this clash, rebellion ceases to be only a political act and becomes an existential choice: to continue and to do something, no matter how small, in the face of a reality determined to prevent you from doing anything at all.

This philosophical framework also finds scientific support. According to a 2010 study published in the Journal of Ethics, titled “Art Therapy for Children Who Have Survived Disaster,” artistic activities—including creative play and movement—provide children in violent environments with a nonverbal way to express fear and help them regulate their emotions in situations where psychological safety is absent.

The study clearly indicates that creative activities help reduce acute stress and create a sense of control within an environment stripped of all normal elements.

Thus, the philosophical and psychological analyses converge. If Camus saw rebellion as creating meaning in a meaningless world, then the circus performances inside Gaza embody this creation.

They represent the moment when young performers—who lost their homes and training space—decide to offer a new show for children, not because the circumstances allow it, but because they do not.

Their act becomes a form of existential resistance before it is artistic or social resistance.

Accordingly, play—as shown in the film—is not only a means of easing the effects of trauma but also a philosophical stance that rejects surrender to the absurdity imposed by war.

It is an attempt to rebuild meaning, not through words but through action: a performance offered, a child laughing, a life that continues moving despite the massacre.

One More Show shows how daily life continued despite everything. The film follows a man making interrupted video calls with his wife and child, who left Gaza, a young man waiting for his brother to reach him under bombardment, and another who returned from Germany to marry the woman he loved before she was killed in the war.

In every scene, the drone is present, trailing people throughout the day. It falls silent only during bombing—when time stops, life freezes, and then resumes minutes later as residents look for bread or buy basic necessities.

The film offers an honest picture: life in Gaza did not stop—despite the massacre—but continued through solidarity, love, and holding on to life.

Through the story of the circus, the film proves that art is not a luxury in wartime but a means of survival and resistance. The young men who lost their homes, center, and equipment continued performing, believing that a child’s laughter in a moment of terror might be the only available lifeline.

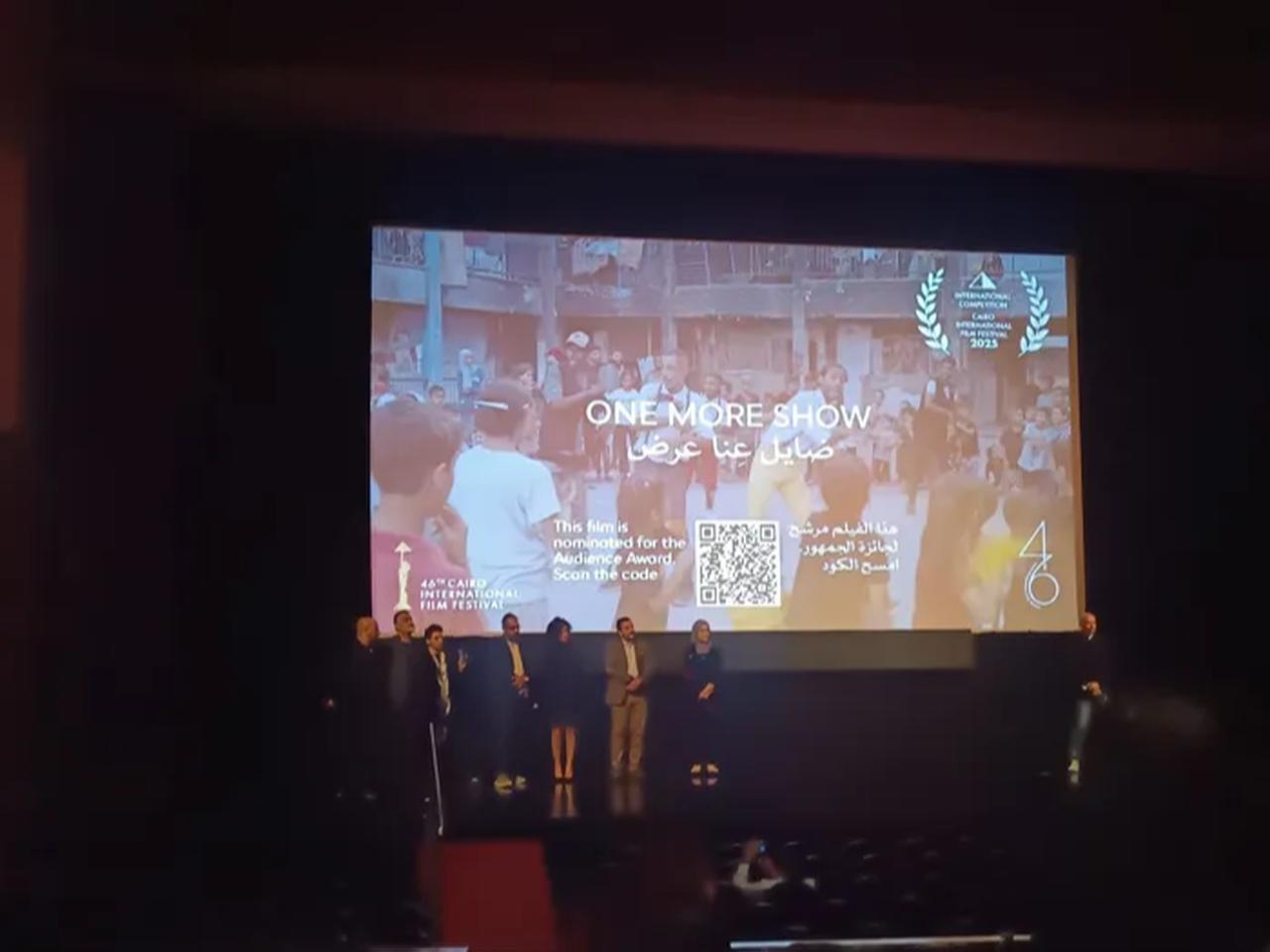

Director Saad attended the festival screening, while co-director Ahmed al-Danaf appeared via a video call from inside Gaza after refusing to leave the Strip despite the war.

The movie also highlights one of the most overlooked dimensions in covering armed conflicts: the therapeutic role of creative activities in protecting children’s mental health.

While fear and bombing dominate the scene, children in the film appear deeply engaged with the circus performances, as if they were reclaiming a brief moment of normal time within an inhumane context.

This directly reflects the findings of the Journal of Ethics study, which emphasizes that artistic practices provide traumatized children with a safe, nonverbal way to express fear and help improve their emotional response when safety collapses.

Accordingly, the film’s circus performances become more than mobile entertainment. They become a psychological coping mechanism in a community experiencing continuous collective trauma.

The young performers, despite losing their homes and training space, kept offering moments that echo structured therapeutic play—even with limited resources and difficult conditions.