The centuries-old Ottoman tradition of Arabic calligraphy, known as khatt, has taken root in modern-day Indonesia thanks to the work of Moroccan calligrapher Belaid Hamidi and his students.

Building on a scholarly chain of transmission (sanad) dating back to the Ottoman Empire, Hamidi’s teaching has sparked a revival of traditional calligraphy in Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) and universities across the Indonesian archipelago.

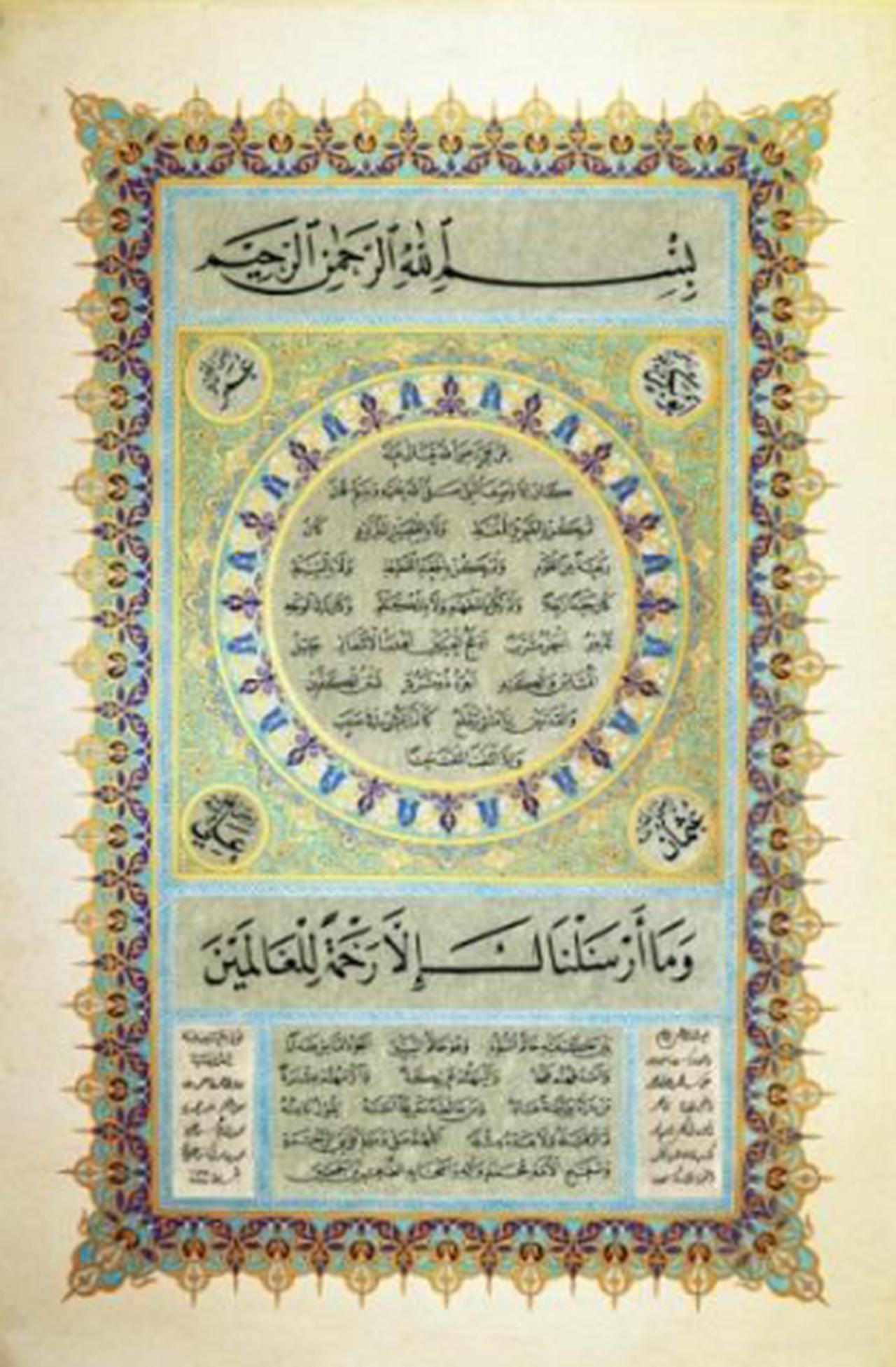

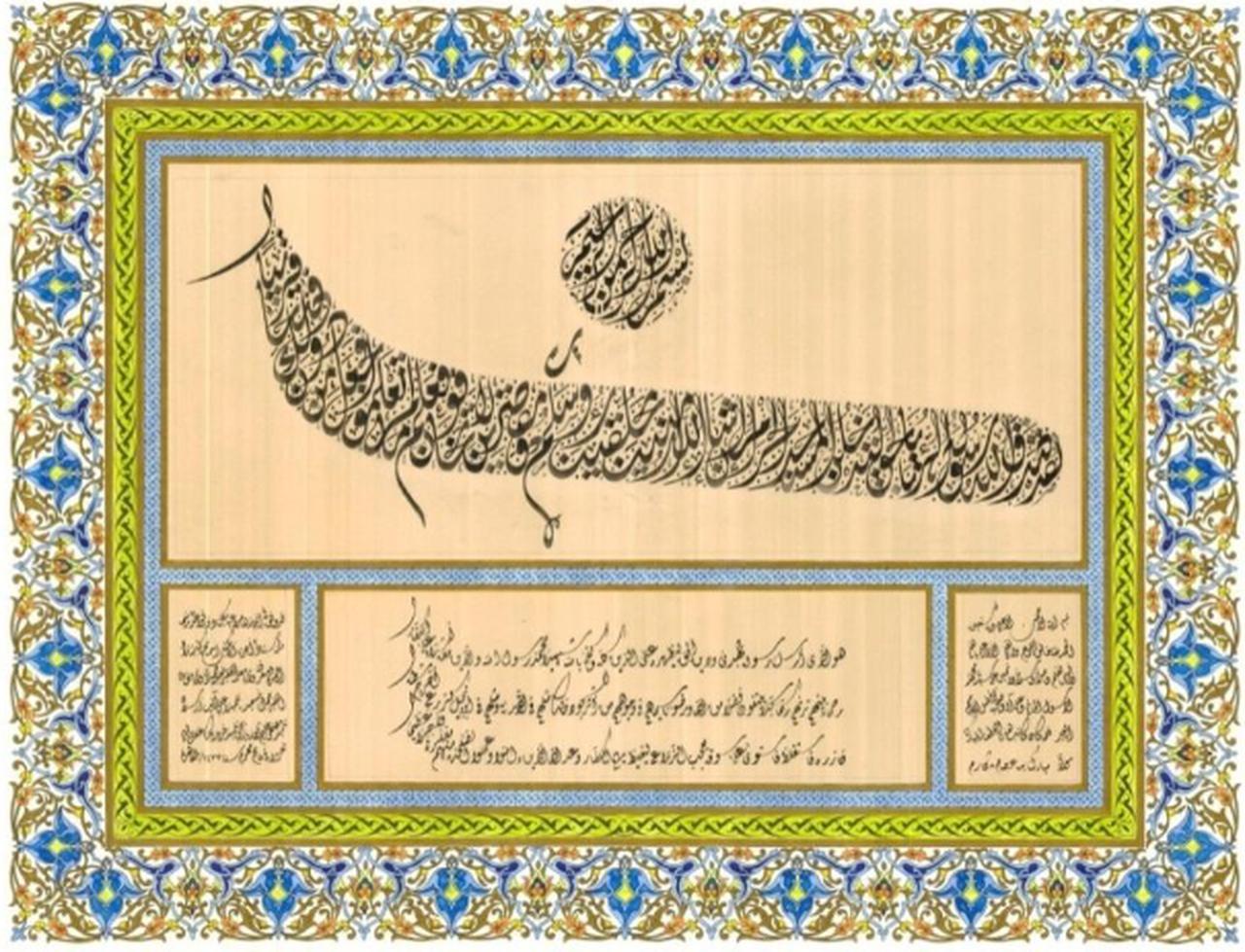

Ottoman calligraphy, once the official writing style of the empire's chancery and religious institutions, relied on a rigorous training system. Students received ijazah, or diplomas, only after mastering script forms under the close supervision of a certified teacher. These diplomas doubled as works of art and formal records of lineage, linking students to generations of calligraphers through an unbroken sanad.

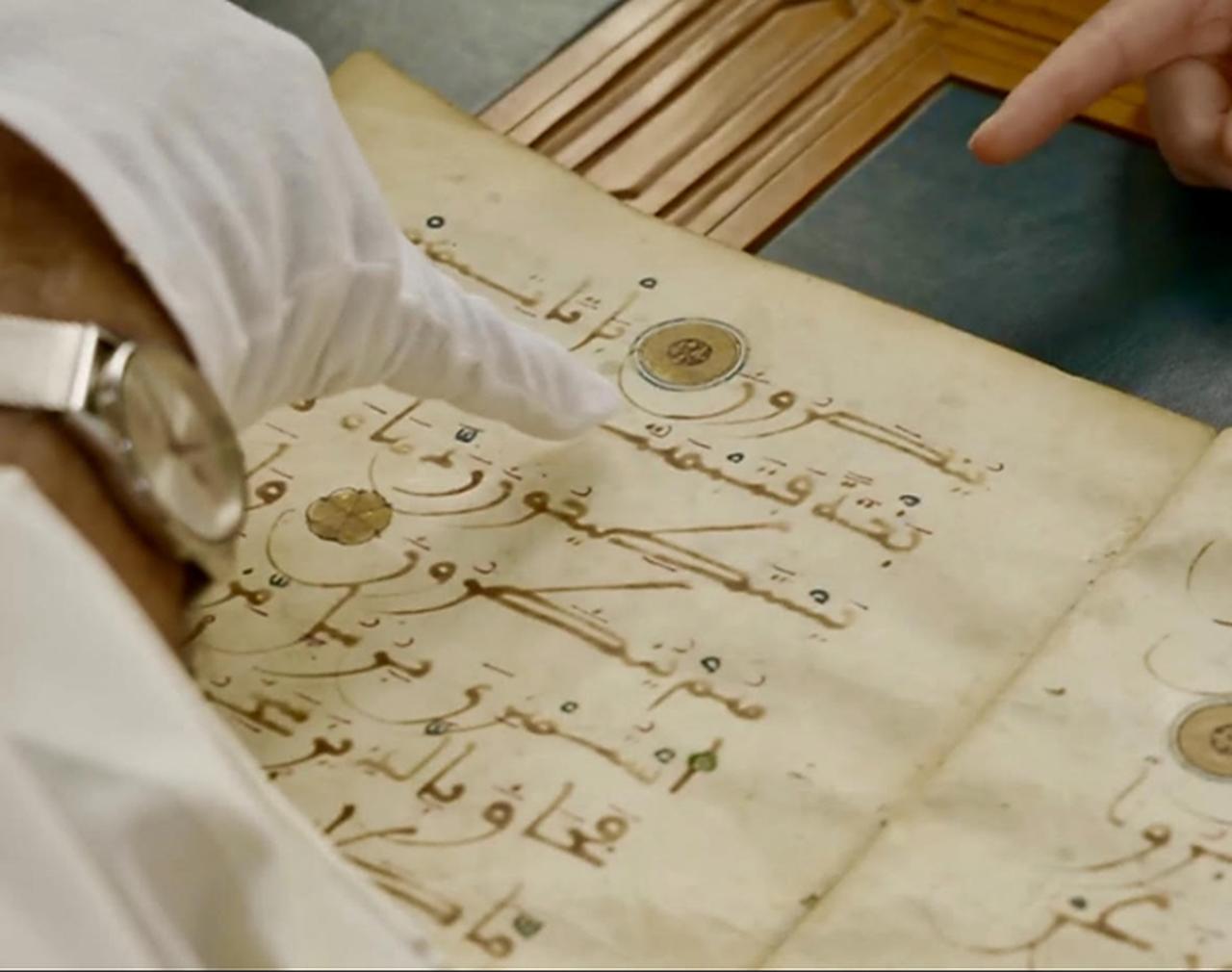

The Ottoman system emphasized mastery in six classical scripts (aqlam al-sittah), including Naskh, Thuluth, Taʿliq, Diwani, Diwani Jaly, and Riqʿah. Key figures such as Hamdullah al-Amasi and Sami Efendi codified these styles, while teaching methods centered on handwritten manuals (kurrasah) and spiritual invocations to instill discipline and reverence.

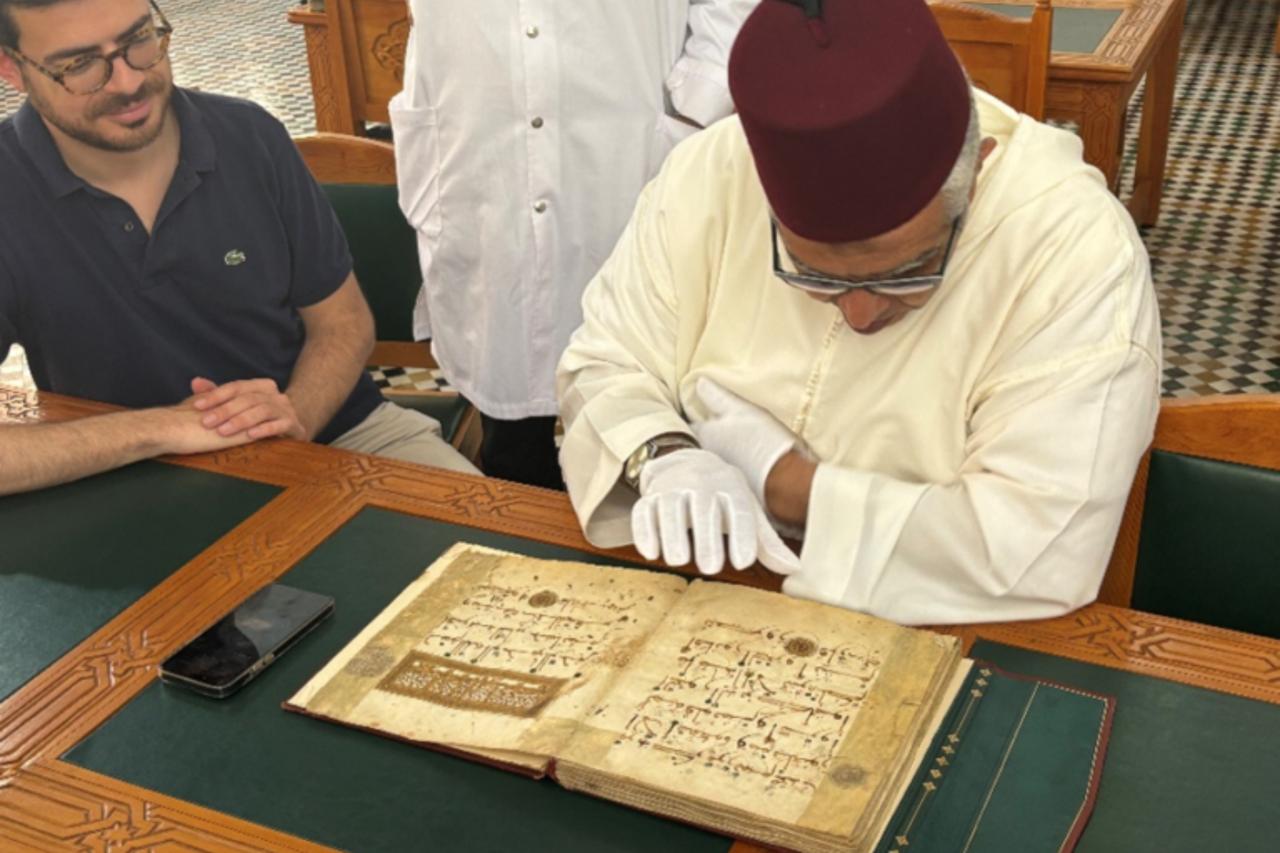

Belaid Hamidi, born in Morocco in 1959, began his formal calligraphy training under Yusuf Zannun in Riqʿah script and later sought out Turkish masters to deepen his knowledge. Between 1993 and 2005, he studied with notable Ottoman-style instructors including Hasan Celebi and Ali Alparslan in Istanbul. Over more than a decade, Hamidi received formal ijazah in five calligraphic styles, establishing his authority as a transmitter of the Ottoman tradition.

Hamidi’s sanad in scripts such as Naskh and Thuluth connects him directly to the legendary Ottoman calligrapher Hamid Aytac through Celebi. For Taʿliq and Diwani, his lineage traces back to 18th-century masters like Muhammad Asʿad al-Yasari and Farid Bik. Hamidi is also credited with adapting the Maghribi-Andalusian style for Ottoman compositions—an innovative fusion not seen before.

While teaching at al-Halaqah Institute in Egypt, Hamidi mentored numerous students from Indonesia, five of whom became pivotal figures in the revival of traditional calligraphy upon their return. These include Muhammad Nur (Ponorogo), Nur Hamidiyah (Ngawi), Alim Gema Alamsyah (Tangerang), Khoiru Rofiqi (Aceh), and Shahryanshah Sirojuddin (Kalimantan).

Through their efforts, Indonesian institutions now host ijazah ceremonies and teach Ottoman calligraphy in both religious and academic settings. Since 2018, Hamidi has also served as a resident instructor at Darul Quran in Tangerang, further solidifying his influence in Southeast Asia.

Notably, at Indonesia’s national Qur’an recitation competition (MTQ) in 2023, 60% of calligraphy entries in the “pure calligraphy” category adhered to Hamidi’s traditional methods, signaling a major shift away from the popular but less orthodox khatt lukis or contemporary artistic calligraphy.

In line with Ottoman tradition, students must learn calligraphy through close imitation, beginning with individual letters and moving on to complex compositions. Before receiving their diploma, students must create a final project—often a Hilyah Sharifah or Qitʿah—containing Quranic verses and hadith. Each diploma includes the sanad, listing all the teachers through whom the knowledge was transmitted.

Although modern technology has enabled remote learning via email and digital platforms, the core of the tradition remains unchanged: mastery through repetition, correction, and an enduring personal bond between teacher and student.