In the final years of the 18th century, as French troops under Napoleon Bonaparte swept through Egypt and disrupted centuries-old Islamic rituals, an unexpected spiritual and political response emerged from the heart of the Ottoman Empire. In the courtyard of Sultanahmet Mosque in Istanbul, the sacred Kaaba cover—known as the kisve-i sherife—was produced not once, but four times, between 1798 and 1801.

This remarkable episode is now being revisited in a recent study by Aysenur Erdogan of Istanbul University, shedding new light on a forgotten chapter in Ottoman religious diplomacy.

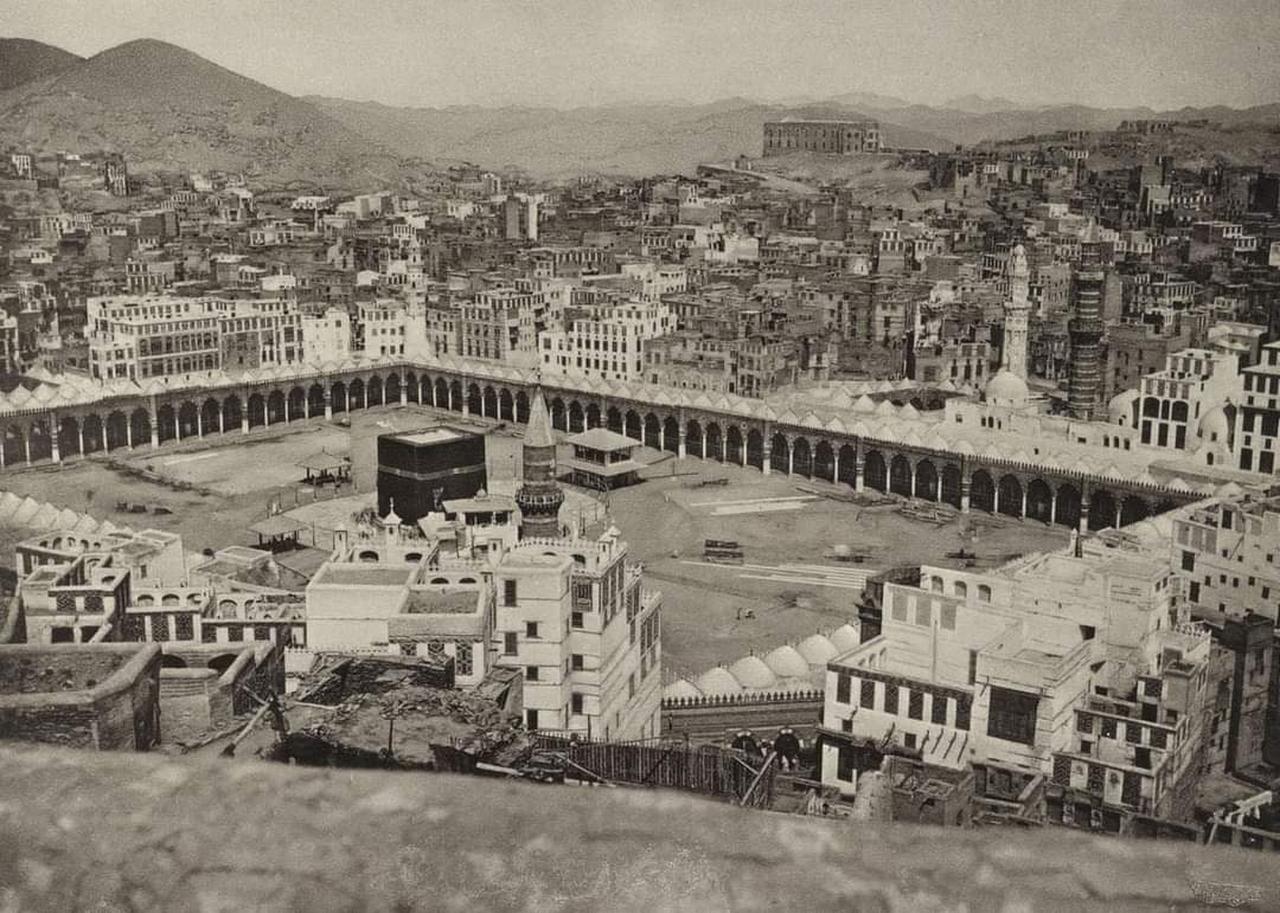

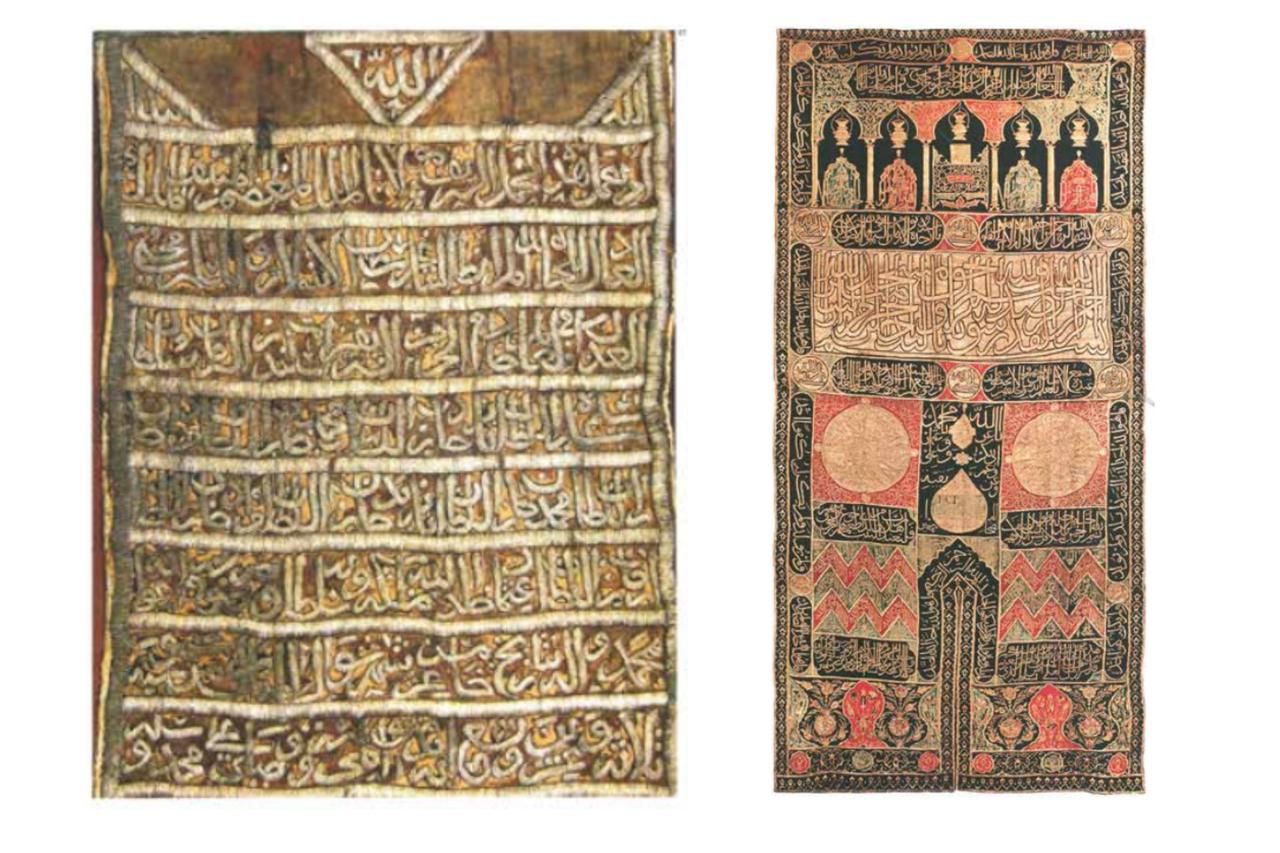

For centuries, the production of the Kaaba’s covering cloth had been an Egyptian prerogative. Starting with the caliphs of early Islam and later institutionalised by the Mamluks, the responsibility was passed to the Ottomans after Sultan Selim I’s conquest of Egypt in 1517. Traditionally produced in Cairo and dispatched with great ceremony to Mecca, the kiswa symbolized the unity of the Islamic world under the caliphate.

But when French forces occupied Cairo in 1798, that tradition was abruptly severed. With Egypt under siege and the pilgrimage route compromised, the Ottomans faced a spiritual and diplomatic crisis: the Kaaba could not be left bare, nor could the sacred tradition be allowed to lapse.

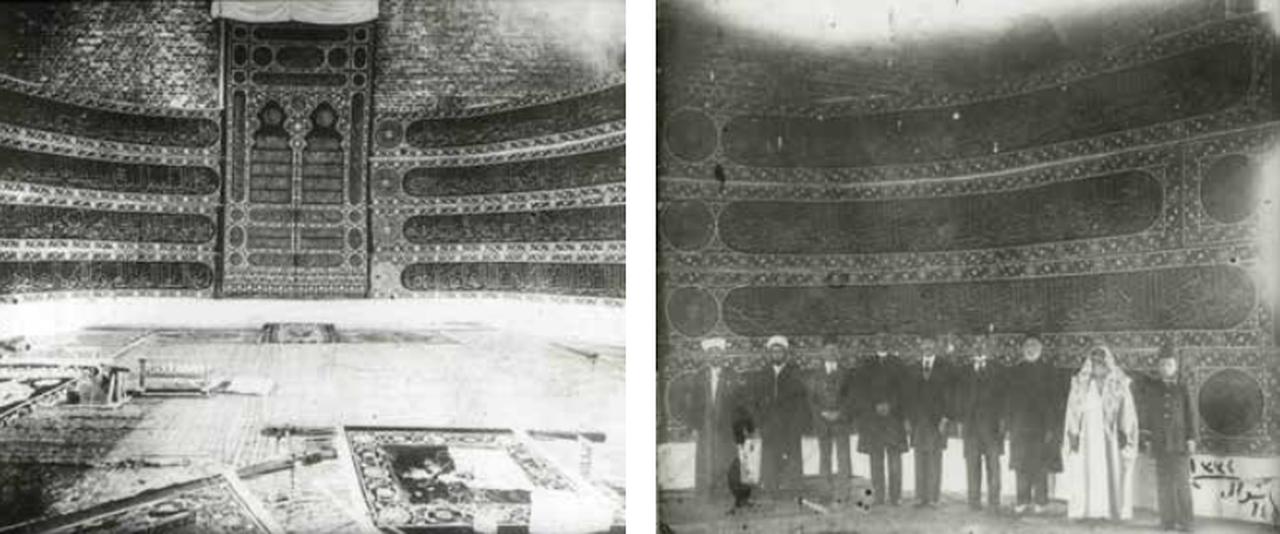

In a decision unprecedented in Islamic history, the Ottoman court transformed the colonnaded courtyard of Istanbul’s Sultanahmet Mosque into a textile workshop. Covered in fabrics sourced from the Mehterhane, the mosque’s arcades became the production centre for the most revered textile in the Muslim world.

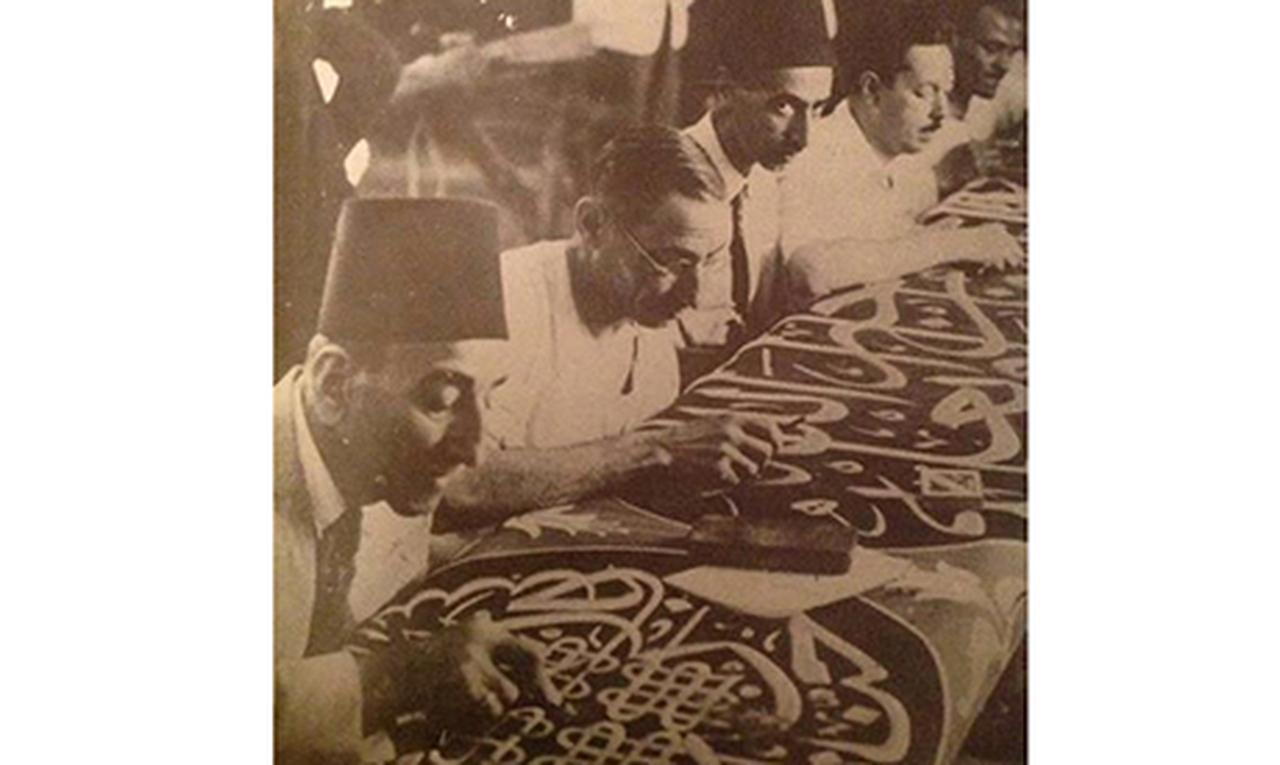

Erdogan’s research reveals the extent of the imperial effort: 32 looms were initially installed, although 10 were later dismantled for inactivity. Silk and gold threads were procured, artisans, including weavers, calligraphers, and embroiderers, were employed, and state archives recorded a staggering 31,469 gurus (old coin) in total expenses. The production extended beyond the Kaaba cover to include the curtain for its door, the key pouch, and the cover for the Maqam of Ibrahim.

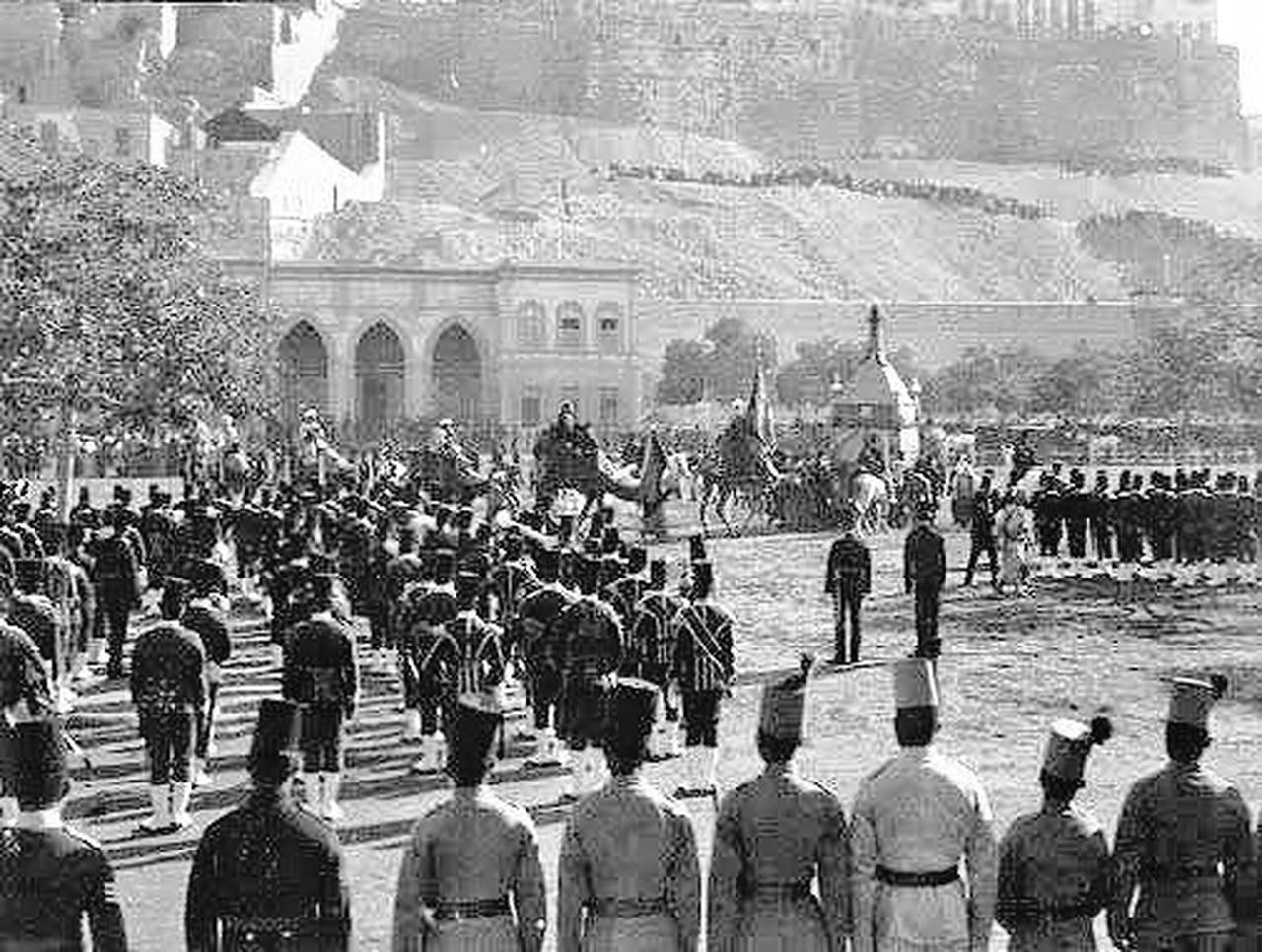

The completion of each cover was marked by an elaborate state ceremony. Ottoman court protocol was meticulously followed. On Dec. 19, 1798, high-ranking officials, religious leaders, and the palace elite gathered at Sultanahmet Mosque. Following prayers, the sacred textiles were placed in decorated crates and carried in a solemn procession to Topkapi Palace. The following day, in the presence of Sultan Selim III, the cover was handed over to the Surre Emini and escorted to Mecca.

This tradition continued for four consecutive years. Each procession became a public spectacle—muezzins and dervishes recited takbirs and tawhids as the cortege wove its way through the streets of Istanbul, passing landmarks such as the Valide Sultan Bath and the Nuruosmaniye Gate.

The production of the Kaaba cover in Istanbul was not only a logistical response but a powerful statement. In a time of geopolitical disruption, the Ottoman state reasserted its role as the guardian of the holy cities and custodian of Islamic tradition. The ceremonies were more than religious events—they were acts of imperial pageantry, demonstrating that even in the absence of Egypt, the Ottoman sultans could uphold sacred duties.

Erdogan’s study further reveals that this temporary shift also exposed practical challenges. In a letter dated 1801, Sharif Galib of Mecca warned that the covers made in Istanbul deteriorated more quickly than their Egyptian counterparts, urging a return to Cairo’s more durable methods.

Though Egypt was retaken in 1801, and the production of the Kaaba cover resumed in Cairo, the Istanbul episodes remain etched in Ottoman ceremonial records. Later, during periods of political disruption or transition—such as under Sultan Mahmud II and even Sultan Abdulhamid II—the tradition was briefly revived in Istanbul, with the Hereke Factory producing the last Ottoman-made kiswa in 1916.

However, due to the war, that final cover never reached Mecca, remaining stranded in Damascus—a haunting symbol of the empire’s decline and the end of an era.