In Türkiye, the act of naming has long reflected the country’s social structures and cultural transitions, much like other countries, but with a stronger resonance.

The names Turkish parents choose for their children have historically mirrored shifts in class identity, political ideology, and aspirations toward modernity. What was once a symbol of upper-class distinction can, within a generation, become a marker of popular taste.

Over the last decade, this transformation has accelerated. Parents today name their children with the same cultural logic they might use to buy property or choose a school—as a social investment signaling status, values, or modernity. Tracing these patterns offers an insider look into how Türkiye’s social fabric has changed from the Ottoman period to the digital age.

Two entire books written about the topic in Turkish, Gurpinar’s 2021 book "The History of Proper Names in Türkiye" and "Sevan Nisanyan’s Dictionary of Personal Names," explore the cultural currents, ideological affiliations, class rivalries, and, ultimately, the intimate dynamics of tesmiye—the tradition of naming a child—that have shaped the past 150 years of Turkish society.

Modern naming trends in Türkiye can be traced back to the mid-19th century, when the Ottoman Empire began integrating into global modernity. The Tanzimat period not only introduced administrative reforms but also birthed a new vocabulary of identity.

Names such as Namik, Kemal, and Resit became synonymous with educated, reform-minded Ottoman elites, signaling the rise of a modern individual identity beyond religious affiliation.

This tradition of “naming through ideology” carried into the early Republic. The state’s secular-nationalist agenda inspired a wave of mythological and pre-Islamic Turkish names like Alp, Tunga, and Yalin. Later, in the urbanizing decades of the 1960s and 1970s, names like Canan, Isil, and Gaye marked the emergence of a new, aspirational middle class seeking distance from rural and religious associations.

Names in Türkiye evolve much like fashion cycles; what once marked a distinction eventually becomes mainstream. Sociologists have long noted this pattern: upper classes set the trend, middle classes imitate it, and working classes normalize it. Once the elite move on, the cycle begins again.

The name Atlas captures this process vividly. It entered the public imagination in the early 2000s when a Turkish celebrity chose it for her son, signaling cosmopolitan sophistication and an affinity with Western aesthetics.

Two decades later, Atlas has become one of the most common male names in Tunceli, a province far from the urban elite circles where it originated.

This journey from the “collage generation” to Anatolian households reveals how the democratization of aspiration erases class distinctions in language, and how the elite continuously search for new linguistic markers of exclusivity.

Nowhere is the sociology of naming more visible than in sports. Football, the country’s working-class sport, offers a snapshot of Türkiye’s lower and middle-income culture.

The national team features players named Mert, Ugurcan, Altay, Berke, Merih, and Caglar, names that have remained socially stable and moderately modern, yet seldom carry an elitist tone.

Basketball, in contrast, has traditionally been a sport of the urban middle class. Names like Alperen, Furkan, Kerem, and Onur dominate its rosters—reflecting educated, metropolitan families with moderate, secular sensibilities.

Women’s volleyball, a sport deeply intertwined with Türkiye’s contemporary gender debates, offers an even sharper illustration. The rise of national player Ebrar Karakurt’s popularity transformed the meaning of her own name, once a conservative favorite derived from Islamic tradition, into a symbol of defiance and queer visibility. What was once a “pious” name became, almost overnight, a coded expression of rebellion matched with her characteristics.

While the private sphere has evolved rapidly, the state’s naming patterns remain frozen in time. Türkiye’s bureaucratic and security elite still reproduces the onomastic culture of the 1980s, the era of Turkish-Islamic synthesis.

Senior officials and intelligence chiefs often carry names like Ibrahim, Hakan, Emre, Teoman, Burhanettin, Nurettin, or Behcet—each echoing a period when nationalism and religious conservatism merged under state ideology. The judiciary, meanwhile, remains even more traditional, dominated by Hanefi, Abdurrahman, Mahmut, Hasan, Cevdet, Ilyas, and Ismail Hakki.

This continuity reflects not only institutional conservatism but also the limited social mobility within the upper echelons of the state. Even as generations change, the symbolic repertoire of power has not.

The contrast between Türkiye’s ruling cabinet and the opposition is equally telling.

Despite its younger average age, the current cabinet’s naming profile—Cevdet, Vedat, Murat, Hakan, Alparslan, Mehmet Nuri, Omer, Abdulkadir—could easily belong to a 1950s administration, as these are names that evoke continuity, hierarchy, and respectability.

The opposition’s “shadow cabinet,” however, tells another story. Ekrem, Ozgur, Selin, Aylin, Gamze, Gulsah, Gokhan, Namik, and Deniz represent a more urban, gender-balanced, and modernist milieu. The difference is not just generational but also representative of Türkiye’s competing moral geographies.

Names in Türkiye also carry ideological weight. Certain choices like Taha, Sumeyye, Bilal, and Meryem often signal conservative or religious backgrounds.

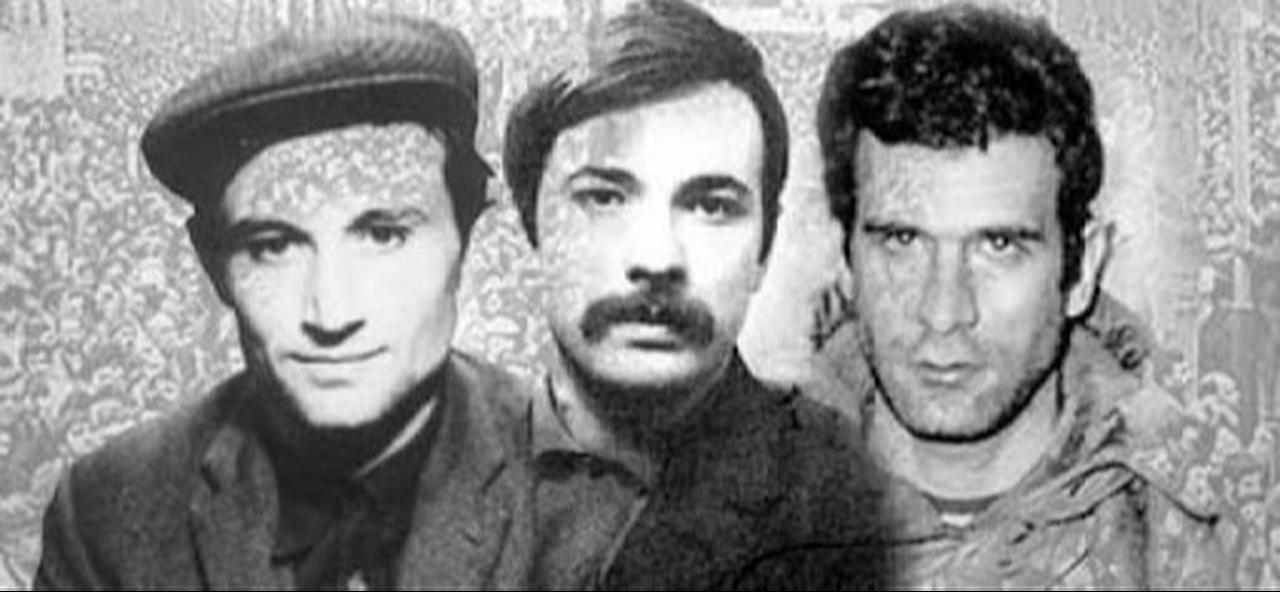

Others, such as Deniz, Baris, Ekin, and Devrim, are associated with leftist or secular families. Among Kurdish and Alevi communities, names preserve ethnic and sectarian identities otherwise marginalized in public life.

During the 1990s, a decade marked by intense political paranoia, this cultural semiotics even gave rise to “onomastic conspiracy theories.” Public debates and books fixated on identifying “crypto-identities” through names, turning a deeply personal choice into a tool of suspicion.

Today, naming patterns in Türkiye are shaped by globalization as much as ideology. Names like Ada, Arya, Ruzgar, and Lina—aesthetically neutral, easily pronounced in English—dominate urban birth registries.

The trend marks a shift toward individualism, cosmopolitan aspiration, and gender-neutrality, all resonant with global middle-class culture.

In this “aesthetic age of naming,” parents are not merely expressing heritage but crafting a brand signaling their education, adaptation of modernity, and detachment from both state and tradition.