On May 16, 1926, Sultan Mehmed VI Vahideddin, the last ruler of the Ottoman Empire, died in exile in San Remo, Italy. Born on Jan. 4, 1861, Vahideddin ascended the throne in July 1918 during one of the darkest periods in Ottoman history. His short reign was marked by war, occupation, revolution, and ultimately, exile.

As the youngest son of Sultan Abdulmecid, he was just three months old when he lost his mother and, shortly after, his father. Raised under special tutelage and educated at the Fatih Madrasa, he grew into a man of intellect, restraint, and deep religious knowledge. He lived a quiet life in the Cengelkoy palace, gifted by his brother, Sultan Abdulhamid II.

Sultan Vahideddin took the throne after the death of his brother, Sultan Mehmed V Reshad. He inherited not a legacy of glory but the ruins of an empire devastated by World War I. The Ottoman defeat led to the signing of the Armistice of Mudros in October 1918.

Fleeing leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) left behind a collapsing state. "I did not sit on a feathered throne but upon the ashes of fire," he famously said. Hoping to prevent further ruin, the sultan tried to cooperate with the British, believing it to be the only path to peace.

Amid this chaos, Mustafa Kemal Pasha was sent to Anatolia with full powers to restore order. Instead, he took charge of the nationalist movement, establishing a different government in Ankara. With support from the Soviets, Italians, and later the French, the Ankara-based forces began gaining strength.

Despite uprisings in favor of the sultan, the nationalist resistance grew. The sultan hoped that after the victory, Mustafa Kemal would return to pledge loyalty. But the opposite occurred.

On Nov. 1, 1922, the Grand National Assembly in Ankara officially abolished the sultanate. Vahideddin retained only the title of caliph. Isolated and under increasing political and personal threats—including instructions to have him lynched if he attempted to flee—he sought refuge.

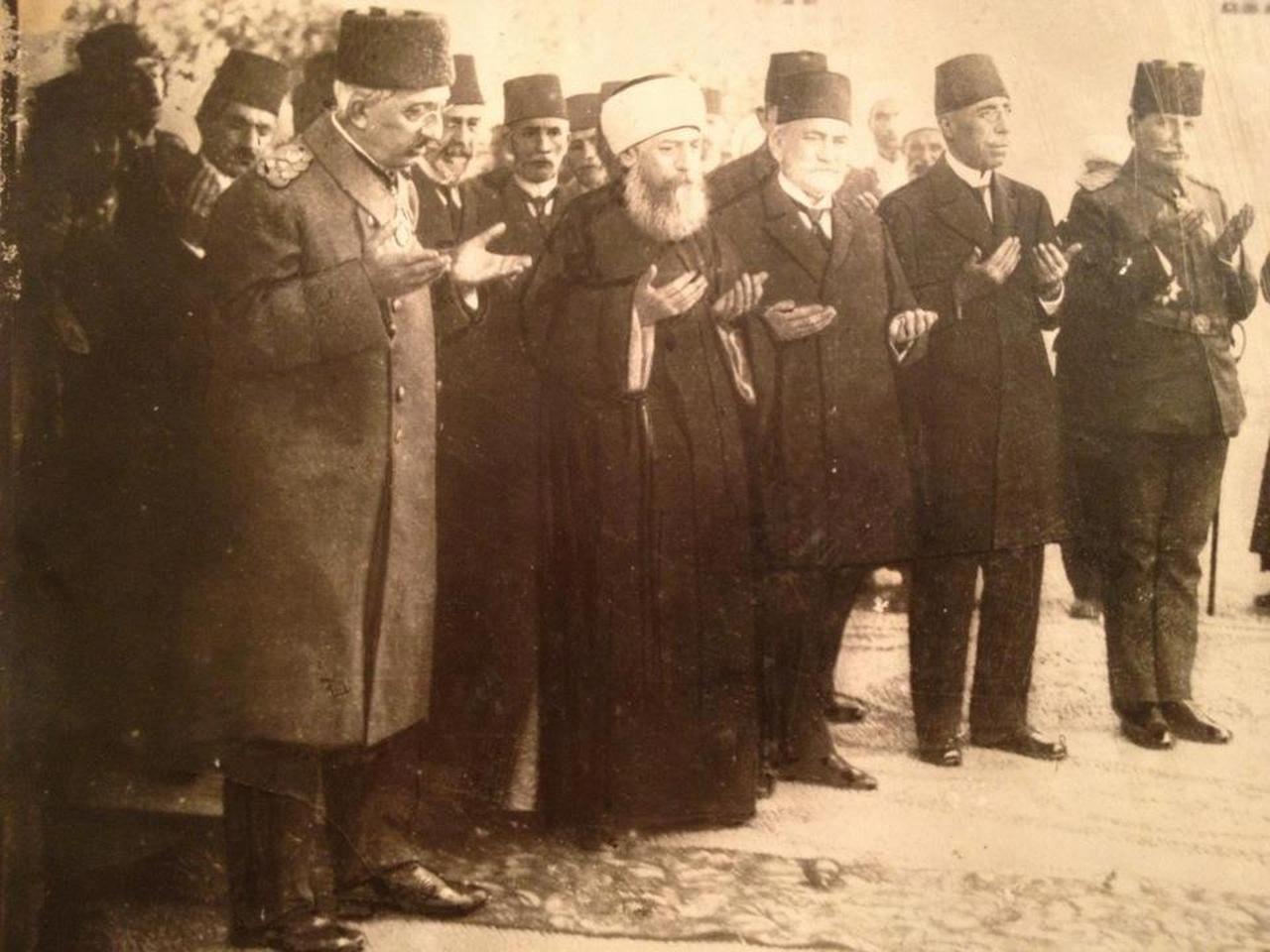

On Nov. 17, 1922, accompanied by his son and loyal staff, he boarded a British warship and left Istanbul. "Hijrah is the tradition of the Prophet," he declared, emphasizing that his departure was not cowardice but a last act of dignity.

The British refused his requests to live in any Muslim-majority region like Hejaz, Egypt, or Palestine. His bank accounts were frozen. Eventually, with the invitation of King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, he settled in San Remo.

Deprived of power and forgotten by the state he once ruled, he spent his last years writing memoirs and making failed attempts to reclaim his throne. When the caliphate was abolished and his entire dynasty exiled, he fell into deep despair.

On May 16, 1926, Sultan Vahideddin died of a heart condition. According to Professor Ekrem Bugra Ekinci, the sultan ran out of money; he even sold his medals. Under his pillow were prescriptions for medicines he couldn’t afford to buy.

His funeral was delayed due to unpaid debts, and creditors even placed a lien on his coffin. With the help of donations, he was finally laid to rest in the Sulaymaniyah complex in Damascus—a city that welcomed him when his own homeland would not.

According to Professor Ekinci, in reflection, the sultan once said, “I made three mistakes: ascending the throne, trusting those around me, and believing in the loyalty of the people.” Of his reign, he remarked, “To protect the nation, we served as a lightning rod. This was our fate.”

Once praised for his intelligence, humility, and administrative skill, Sultan Vahideddin’s life ended not with glory, but with a sorrowful silence—symbolic of the empire he represented.