The Asiret Mekteb-i Humayun, or Imperial School for Tribes, was a special institution established during the reign of Abdulhamid II in 1892, primarily for the children of Arab tribes.

Education at the school continued until February 1907, after which it was closed due to political and economic reasons.

As its name suggests, the school was designed as an institution where children from tribal backgrounds would receive education and upbringing.

However, the school's primary objective was not conventional education, but was driven more by political—administrative, religious, and ideological—motives than by purely educational goals.

An abandoned palace known as Saray Sultan Esma in the Kabatas district of Istanbul was chosen to serve as the school's main campus. Additionally, five adjacent houses in the same district were acquired to provide housing for the students.

The idea of establishing the Asiret Mektebi was part of Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s (1876-1908) efforts to consolidate state control and implement his Pan-Islamic policy, as the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula were among his greatest concerns.

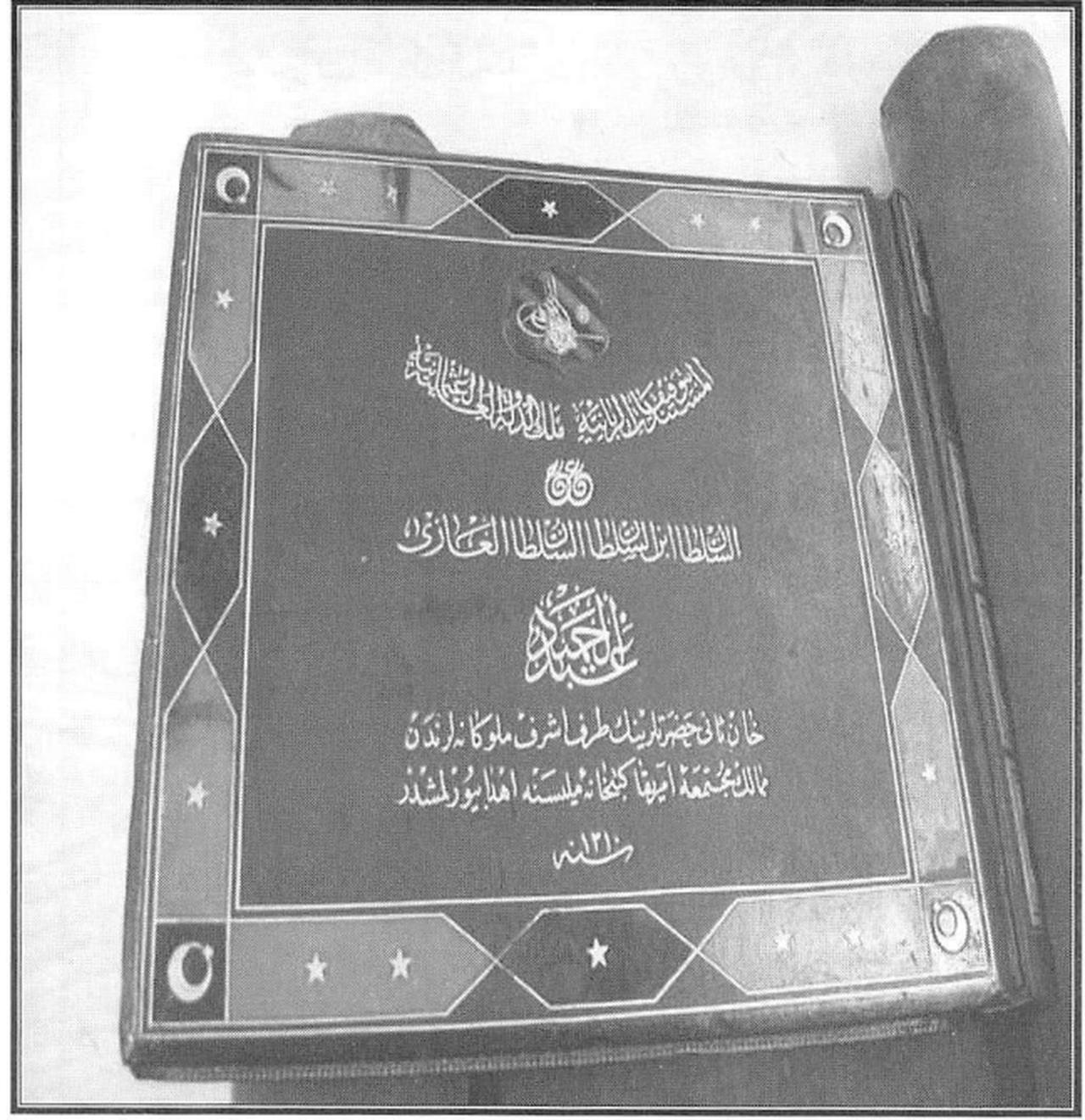

Documentary evidence shows that the sultan personally took the school’s affairs very seriously. Organizationally, he was titled the school’s "patron" and "honorary director."

The Ottoman state aimed to raise these children within the ideologies of Pan-Islamism and Ottomanism. Through this education, they would be taught Turkish and brought into closer contact with Ottoman culture. By instilling a sense of Islamic and Ottoman identity, the state sought to strengthen its loyalty to the sultanate and the caliphate.

Ottoman documents reveal that Sultan Abdul Hamid II personally oversaw the establishment of the Asiret Mektebi, taking a direct interest in its organization and curriculum. He drafted its internal regulations and planned for graduates to be appointed to both civil and military positions.

This approach set the school apart from other military institutions at the time, which typically restricted graduates to military roles only. It also explains how the school was founded and fully equipped in less than three months.

Sultan Abdulhamid II initially enrolled children of leading Arab tribal families in a state-run school. Later, Kurdish, Hamidiye, and Albanian tribal children were also admitted to fill quotas and expand the program.

The aim of the Asiret Mektebi was a strategic move to reassert central authority over tribes in remote areas where state control was weak.

Sultan Abdulhamid’s vision was to educate the children of leading tribal chiefs under state supervision, fostering their loyalty to the empire. This approach aimed to curb European influence over the tribes and strengthen Ottoman control in tribal regions.

This strategy proved effective. Amid increasing foreign influence throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the school functioned as a political tool: tribal leaders who sent their children demonstrated loyalty to the sultan, and graduates were directed toward state service rather than traditional tribal leadership—thereby reinforcing Ottoman control over distant regions.

After 15 years of operation, preparations were made in 1908 for the return of students from their usual summer break. However, the school never reopened that winter.

From that point on, no new students were admitted to the Asiret Mektebi, and it was eventually converted into a primary school.

According to Dr. Eugene Rogan in his book "Tribal School in Istanbul," the Ottomans viewed tribal communities with deep suspicion.

Officials in both the imperial capital and provincial administrations frequently used derogatory and dismissive language, depicting tribes as ignorant, uncivilized, and socially backward.

Cultural bias was evident in the terminology used—words like cehl (ignorance), which implied shortcomings in religious practice, and vahset (savagery), used to describe the perceived lack of urban development among Bedouin and nomadic communities.

In 1886, 48 students from marginalized Arab provinces such as Hejaz, Yemen, and Tripoli were sent to study at the Ottoman Military Academy.

After three years, they graduated and were assigned duties. Before returning to their home regions, a group of these young officers was received by Sultan Abdulhamid II following Friday prayers.

The sultan had prepared a draft message through his secretary, emphasizing the importance of their return to serve the state.

Students at the Asiret Mektebi studied both religious and modern sciences, alongside military training, eventually earning high ranks upon graduation.

The duration of study ranged from five years for boys aged 12 to 16. Each student received a monthly stipend of 30 kurus and was granted family leave once every two years, with travel expenses covered by the school.

Upon completion, graduates could continue at the Royal School (a civilian institution), after which they were awarded the rank of Kaymakam (district governor) and could return to their regions.

The curriculum also included instruction in Persian, Turkish, and French.

The duration of study at the school was five years. Each student was entitled to a home visit once every two years, with travel expenses covered by the state. Exam results were sent directly to the sultan for review.

The school conducted regular assessments and one final exam each academic year. At the end of the final exam, answer sheets were submitted to the school administration for grading.

These exams were held at the end of the Islamic month of Shaban each year, and classes were suspended during the month of Ramadan—except for Quran lessons.

The official summer break began each year on the fifth day of the Hijri month of Shawwal.

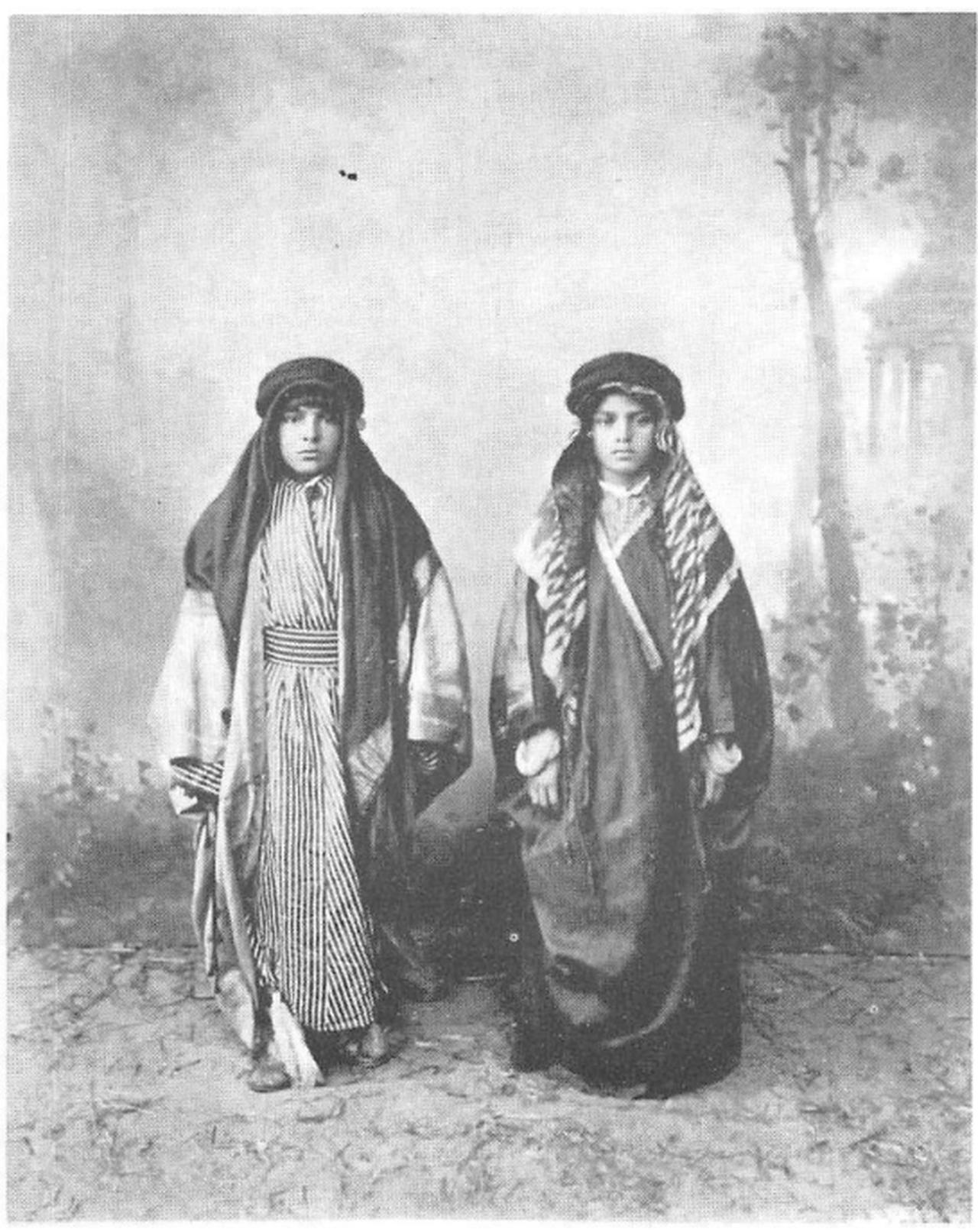

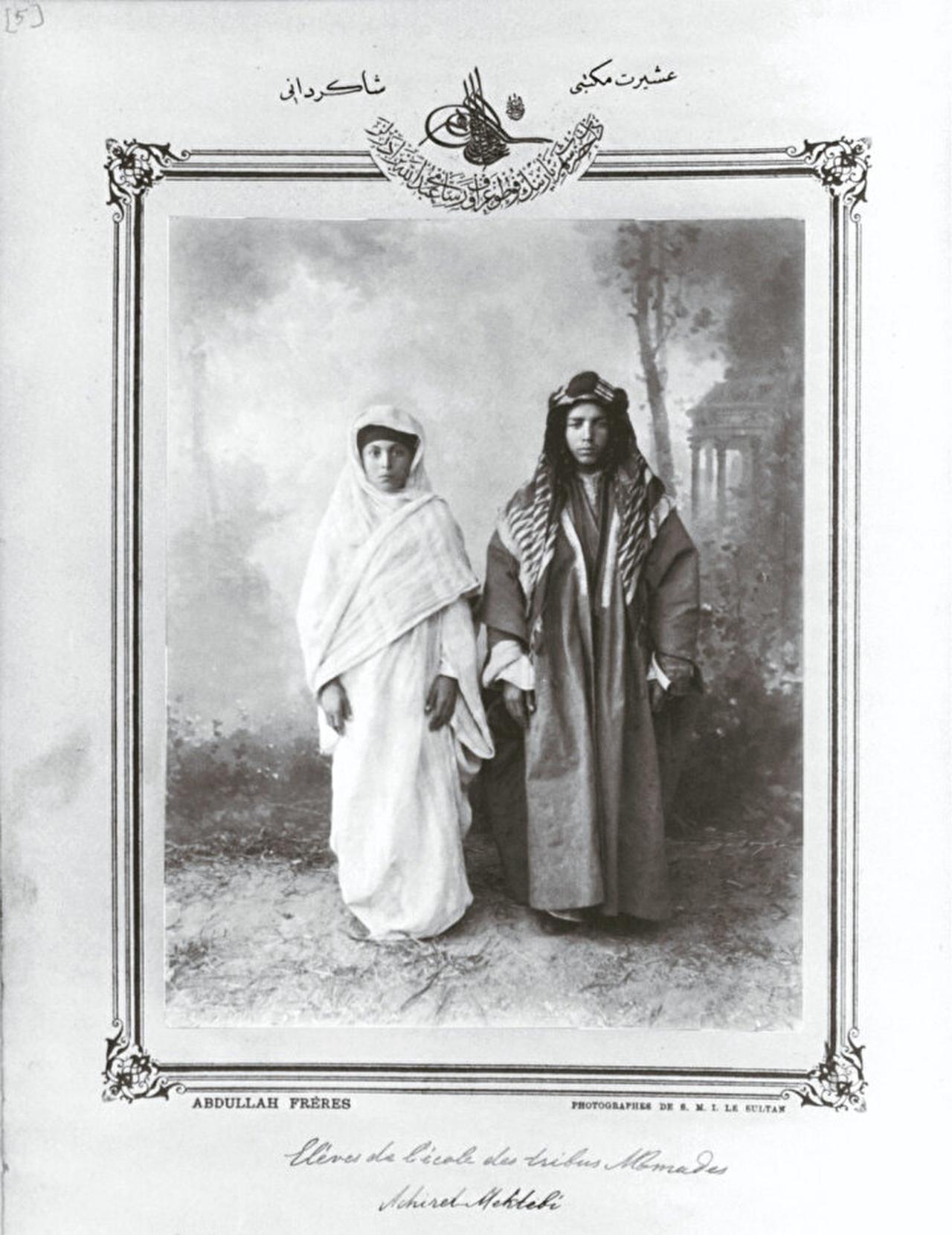

Eugene Rogan examines the clear contradiction in the daily life of the young Bedouin through a perceptive comparison of photographs taken by the sultan’s photographer, Abdullah Freres.

These photos, presented by Sultan Abdul Hamid as gifts to national libraries in France and the United States in 1893 and 1894, show the students dressed in their traditional local attire in a photography studio, standing rigidly with serious expressions facing the camera.

In contrast, other photos depict the same students in front of the school wearing a modest European-style school uniform, reflecting the state’s attempt to impose a different lifestyle on this group.

These images clearly document the tension between local identity and the modern experience imposed by the Ottoman regime, without passing judgment or expressing emotion.