Archaeologists report the earliest known cases of artificial mummification by smoke-drying.

The findings show that hunter-gatherer communities across southern China and Southeast Asia prepared bodies over low, smoky fires before burial—well before celebrated traditions in Chile and Egypt.

Published on Sept. 15, 2025, in PNAS, the study analyzes pre-Neolithic burials dating between roughly 12,000 and 4,000 years ago, concluding that many bodies were smoke-dried before interment and arranged in compact, tightly bound postures.

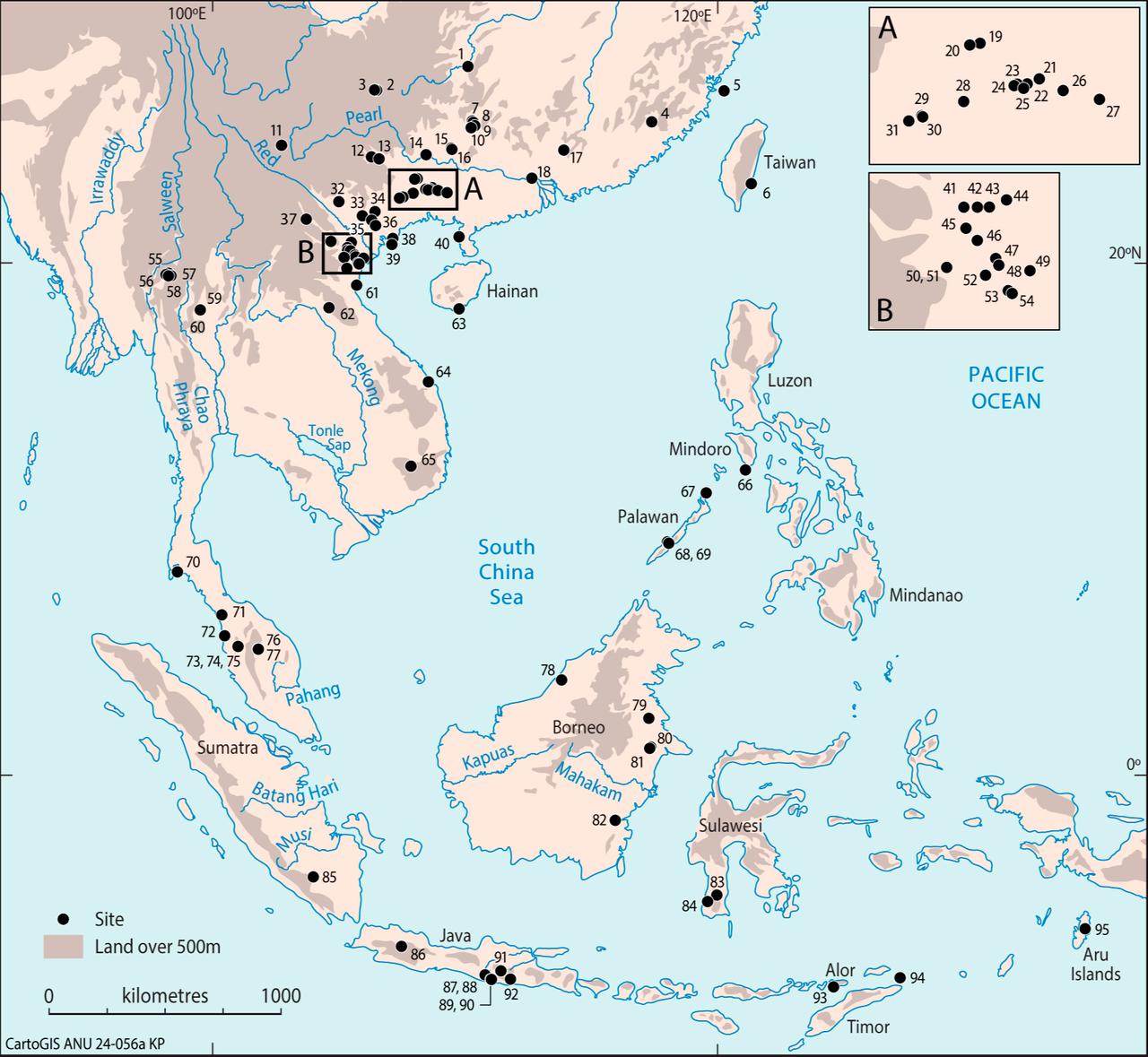

The team examined 54 burials from 11 archaeological sites across the wider region.

To check whether heat, smoke, or open flame played a role, the authors used X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)—lab techniques that probe bone microstructure for thermal alteration that might not show up on the surface.

Results across scores of samples indicate that heat exposure was common, supporting a deliberate, low-temperature smoking process rather than full cremation.

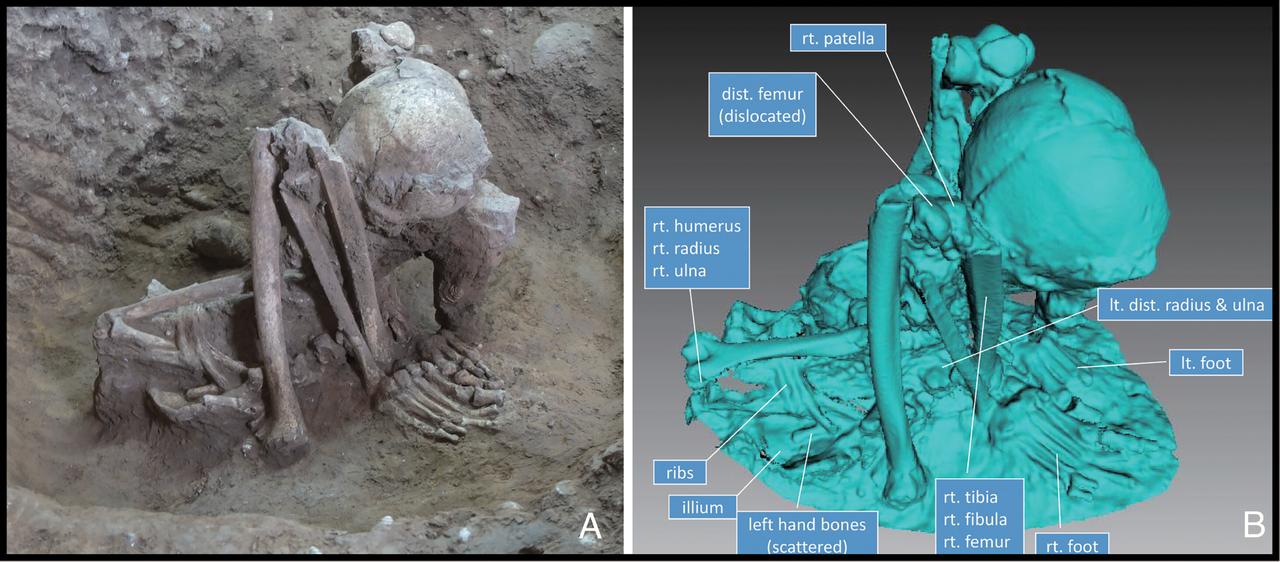

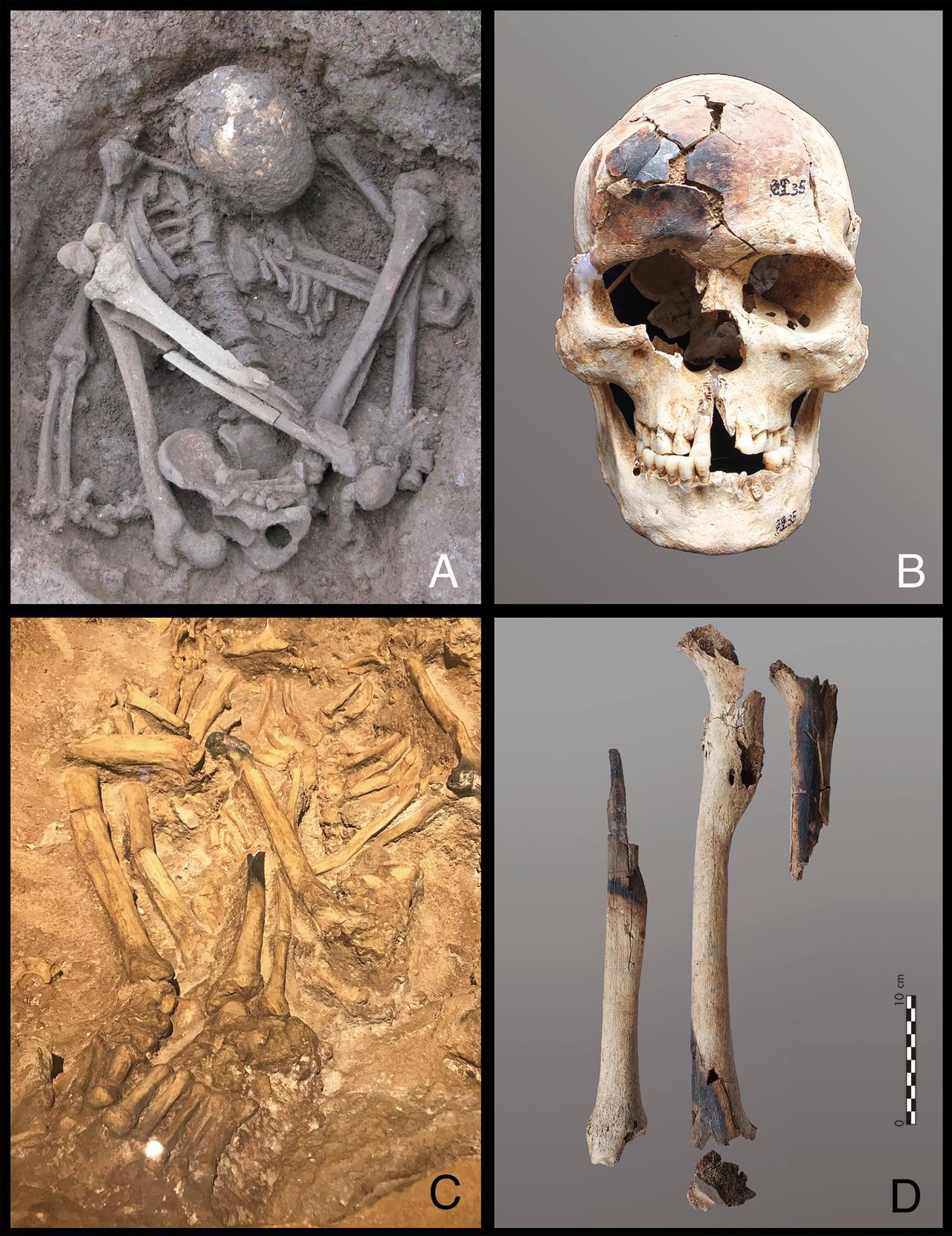

Many individuals were found in hyper-flexed or squatting positions so compact that no empty space remained between limbs and torso—an arrangement difficult to achieve with fresh bodies. T

This pattern, the authors argue, fits a scenario in which soft tissue had already dried down, with only skin remaining when the body was finally buried.

Charring turns up most often on the lower limbs, elbows, and the frontal area of the skull, while other parts show only smoke-induced blackening.

Such localized effects point to bodies set above controlled or semi-controlled fires for extended periods, rather than being burned throughout. FTIR measurements back this up, with most samples showing signatures of low-intensity heating.

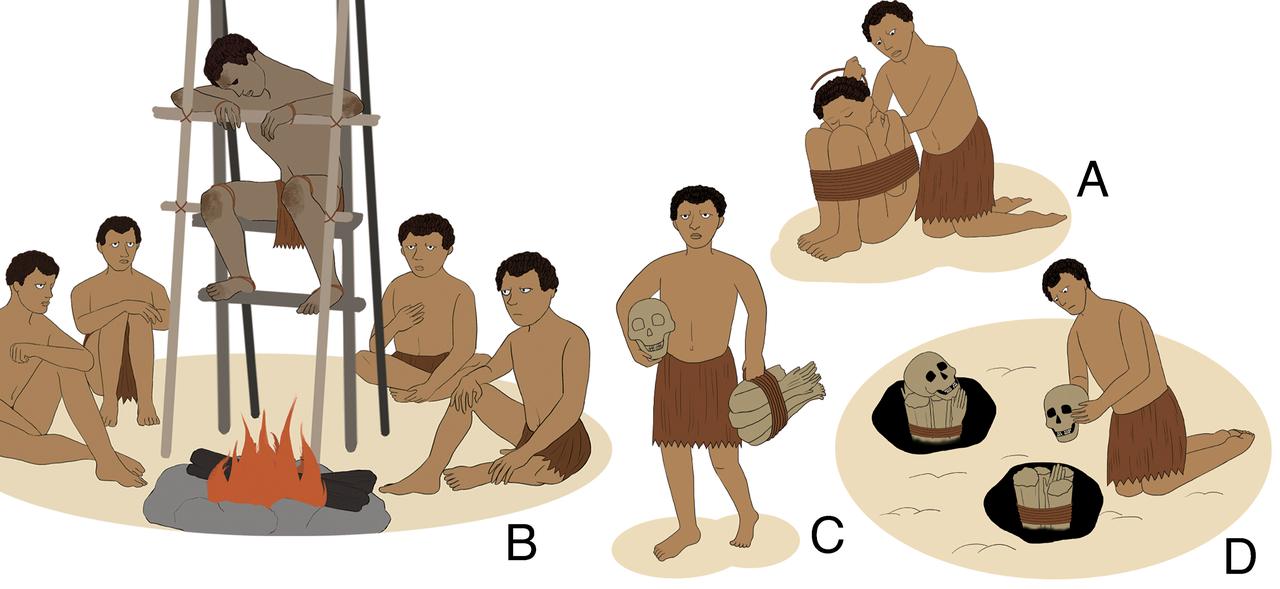

Modern accounts from Papua’s Highlands and parts of Australia describe mummification by smoking, with bodies tightly compressed soon after death and dried over a low fire—sometimes for months—before being kept indoors and brought out on special occasions. The new findings match those practices closely and help make sense of the archaeological pattern.

Based on combined field observations and lab results, the study identifies nine sites across southern China and northern Vietnam, plus one in Indonesia, as confirmed examples of smoke-dried mummification, with additional sites showing closely comparable traits.

Bones that appear out of place and cut marks around joint ends may reflect practical steps to bind limbs more tightly or to release joints once rigor mortis had set in, as well as post-mummification handling—rather than ritual mutilation.

Craniofacial and genomic links tie these pre-Neolithic people to the ancestors of Indigenous communities in New Guinea and Australia, suggesting long-term biological and cultural continuity.

The tradition of smoke-drying may therefore go back further and extend more widely than the present archaeological record captures.