History has a way of whispering its secrets—if you listen closely.

The night was thick with whispers, slithering through palace corridors and settling in the hearts of those who dared to listen. On June 4, 1876, Sultan Abdulaziz, the former sovereign of the Ottoman Empire, was found in a room in the Feriye Palace on the Bosphorus, his wrists slashed, a pool of blood staining the chaise beneath him. The official story? Suicide. The truth? Perhaps something far more sinister.

The Ottoman Empire in 1876 remained a formidable power. Its dominion stretched over 12 million square kilometres, across what are now 35 countries. Its capital, Istanbul, was the fifth-largest city in the world. The empire had a population of 64 million, commanding the world’s fourth-largest army and the third-largest navy.

Sultan Abdulaziz was a strong ruler, fiercely resistant to foreign encroachment, dismissing ministers he suspected of harboring Western sympathies. Yet while the empire projected strength under his rule, there were those in Europe who saw advantage in curbing Ottoman power—and disaffected men at court who sought the sultan’s removal.

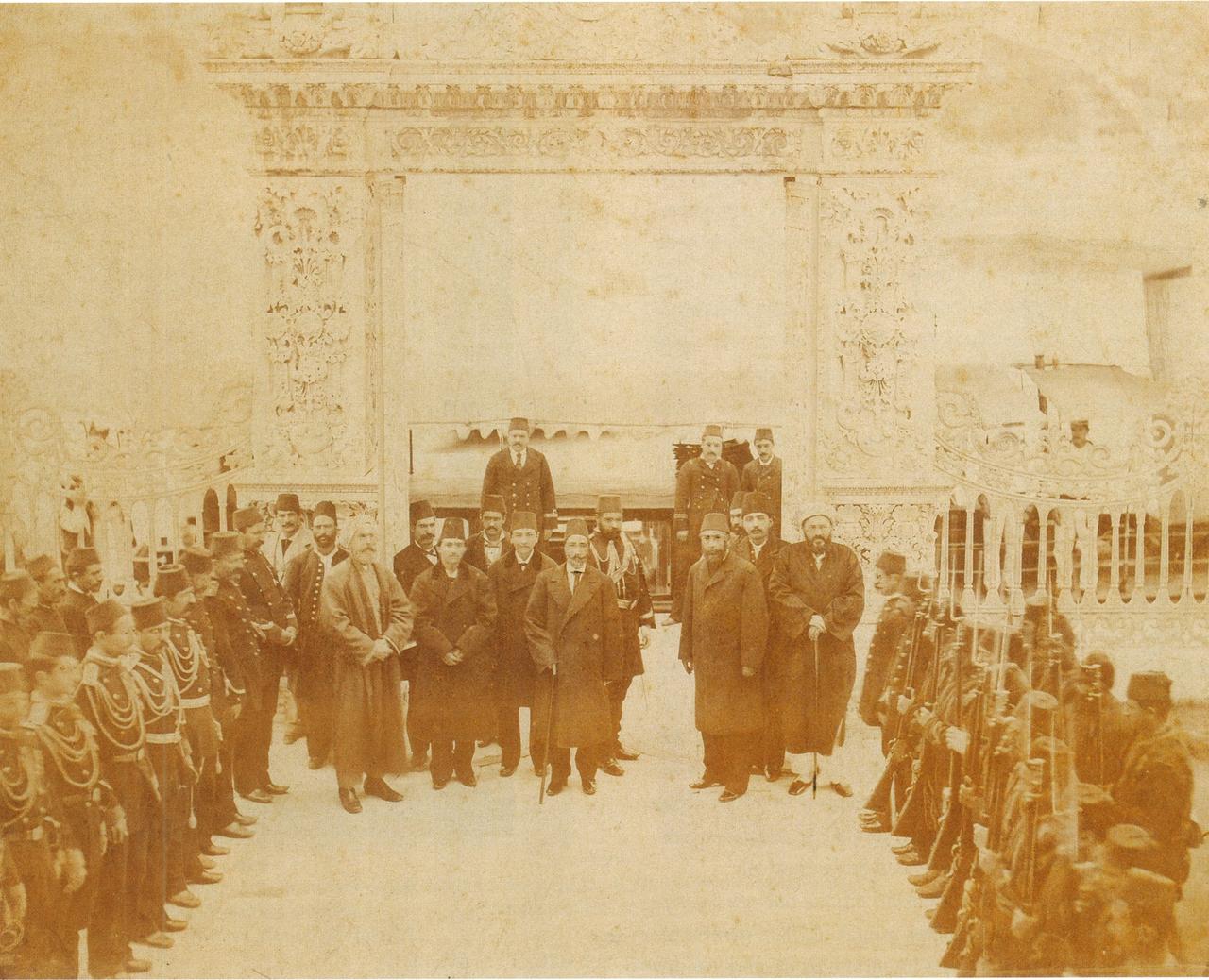

Only days before his death, Sultan Abdulaziz was deposed in a coup led by Midhat Pasha, the reformist grand vizier, and Huseyin Avni Pasha, the chief of staff. He was replaced by his nephew, Crown Prince Murad, a liberal prince the conspirators believed they could control. Sultan Abdulaziz, stripped of power, was confined under guard at the Feriye Palace. On the morning of his death, he performed his ablutions, prayed, and afterward requested a pair of scissors to trim his beard.

His mother, Pertevniyal Valide Sultan—the queen mother—sent him her embroidery scissors and a small hand mirror. Hours later, when no one had seen him and his door remained locked, alarm spread through the palace. The valide sultan ordered it broken down. Inside, Abdulaziz lay on his side, clothes drenched in blood. The women of the harem wailed, their cries echoing across the Bosphorus.

Huseyin Avni Pasha hurried to the scene. Abdulaziz was still alive, but barely—both wrists deeply slit, one side of his beard torn, his teeth broken, and a dark bruise marked his chest. The pasha did not summon medical help. Instead, he ordered the sultan to be carried to the kitchen of the palace police station—a calculated delay to ensure Abdulaziz bled to death. To conceal the violence, curtains were torn down and wrapped around the body, leaving only the arms exposed. The first doctors summoned refused to declare death by suicide. But others were persuaded.

The sultan’s daughter, Princess Nazime, claimed to have witnessed her father’s murder. Pertevniyal Valide Sultan never believed her son had committed suicide. She is said to have hidden his bloodied clothes in a chest, convinced he had been assassinated.

Her suspicions seemed confirmed in a chilling confession attributed to one of the alleged assailants: “Fahri Bey … held back his arms. Haji Mehmet and Algerian Mustafa sat on their knees. And I cut his veins in his left arm as deep as I could with a pocketknife. I pierced his right arm in several places with the knife.” Whether apocryphal or genuine, the words capture the horror of that day.

Tragedy compounded. Sultan Abdulaziz’s third consort, Nederek Kadinefendi, died seven days later. Some accounts suggest childbirth, while others cite grief. Her brother, Captain Cerkes Hasan, sought vengeance. He stormed a cabinet meeting at Midhat Pasha’s house, killing Huseyin Avni Pasha and the Foreign Minister Mehmed Rashid Pasha, and wounding others, before being captured and executed.

For a time, Midhat Pasha prospered under Sultan Murad V and later Sultan Abdulhamid II. But in 1881, he was arrested for his role in Sultan Abdulaziz’s death. His death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and he was exiled to Ta'if, Hejaz, where he was strangled in 1883.

Sultan Murad V was deeply traumatized by his uncle’s violent death and grew increasingly suspicious of Midhat Pasha. He suffered a nervous breakdown, and after just 93 days on the throne, his reign ended. Realizing he would never regain Murad’s trust, Midhat Pasha orchestrated another coup, deposing him in favor of his younger brother, Abdulhamid. Though Sultan Abdulhamid promised constitutional reform, within two years, he abolished the constitution and restored autocracy. Murad spent the rest of his life in confinement at the Ciragan Palace.

For more than a century, the circumstances of Sultan Abdulaziz’s death remained shrouded in mystery. Then in 2007, a discovery in the Topkapi Palace archives revived the debate. A bloodied nightshirt and undergarments, believed to belong to the slain sultan, were found.

Perhaps preserved in secret by the distraught valide sultan, they bore witness to violence. Experts concluded that the official verdict of suicide was improbable. Sultan Abdulaziz had almost certainly been murdered.

What is your verdict on what happened on that fateful morning in June? Perhaps we will never know, but the truth of the case echoes through the corridors of the Feriye Palace, lingering on the blood-stained clothes kept hidden for so long.

About the author and 'The Sultan’s Salon'

They say history is learnt from books and dusty archives. But what if I told you, it also seeps from every stone and whispers through every silk thread? Welcome to “The Sultan’s Salon,” where twice a month I’ll lift the veil on an Ottoman treasure—and the very personal story it holds.

Because behind the throne and all the political intrigue, the House of Osman was, first and foremost, a family. Like every family, they laughed and cried, loved and feared, dreamt and despaired, suffered and survived. And like every family, we had our secrets.

I am Ayşe Osmanoğlu: descendant of Sultan Murad V and Sultan Mehmed V Resad; graduate in History and Politics from the University of Exeter, with an M.A. in Turkish Studies from SOAS, University of London; and author of “The Gilded Cage on the Bosphorus” and “A Farewell to Imperial Istanbul.” In this column, I will uncover the past through the lens of a particular place or a tangible object—somewhere you can visit, something you can almost touch: a palace hammam, the silk hem of a Sultan’s kaftan, a piano played by an enlightened prince. Through these witnesses to history, the past comes alive, and we catch a fleeting glimpse of a lost world.

Think of this column as your invitation to a private salon—where we meet after wandering Istanbul’s palaces and museums together, peeking into forgotten rooms and glass display cases, and discovering that Ottoman history, at its heart, is not just about conquest and empire. It’s about people. It’s about family. It’s about my family.

Until we meet again in the next “Sultan’s Salon.”