In the heart of old Istanbul, the garden of Hagia Sophia—one of humanity's most enduring architectural marvels—hid secrets long buried beneath its soil. Between 1935 and 1939, the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), under the leadership of Alfons Maria Schneider, conducted a series of archaeological excavations that revealed previously unknown architectural remains and artifacts dating back to the time of Emperor Theodosius.

These excavations, carried out during a pivotal moment when Hagia Sophia was transitioning from mosque to museum, brought to light ancient columns, intricate mosaics, and even traces of earlier church structures that predated the famed 6th-century building commissioned by Emperor Justinianus.

The project was the result of an intensified interest in Byzantine history, particularly in Istanbul, where European powers had long competed for cultural and archaeological dominance. The German and American-led Byzantine Institutes were instrumental in drawing attention to Eastern Roman (Byzantine) heritage.

While the American-led team focused on uncovering mosaics inside the Hagia Sophia, the German team concentrated on the external garden area. According to an academic study, with approval from Türkiye’s Ministry of Education, the archaeological digs were launched shortly after Hagia Sophia’s formal conversion into a museum in December 1934.

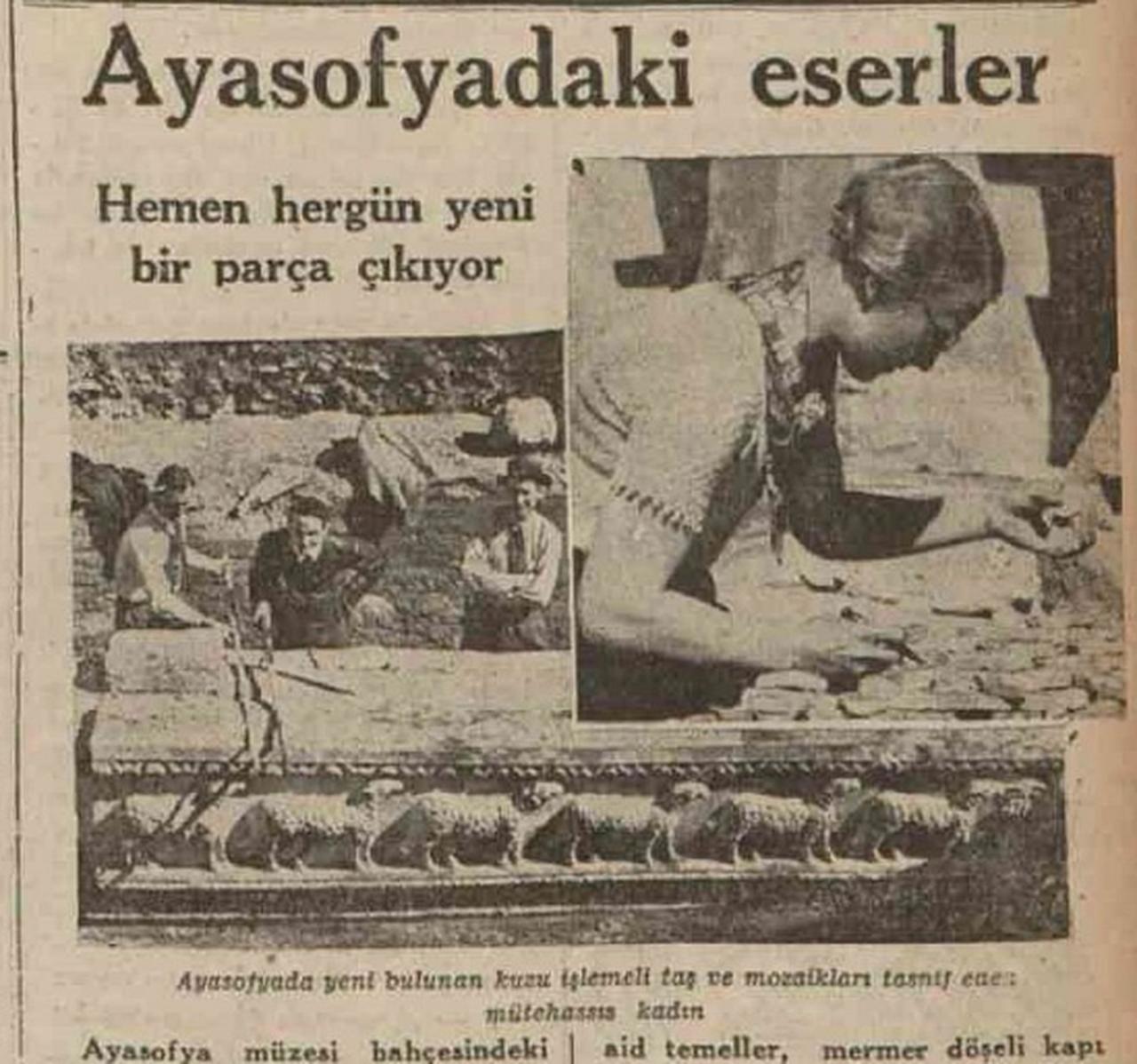

Beginning on January 27, 1935, the excavation rapidly revealed impressive results. Within two weeks, newspapers reported the unearthing of ancient marble columns, foundations, and decorative features believed to date back to the Theodosius-era church—nearly 150 years older than the current structure. Schneider later confirmed in his 1941 Berlin publication, “Die Grabung Im Westhof Der Sophienkirche zu Istanbul,” that significant architectural remnants were linked to the earlier church.

Findings included arched cornices adorned with lotus and palmette motifs, sculpted lambs believed to represent the twelve apostles, richly decorated soffits with doves and fish, and the foundations of what may have been the original propylon (entrance gate) of the Theodosian church.

The Turkish press covered the excavations with fascination, publishing daily updates from the garden of Hagia Sophia. Türkiye's newspapers like Milliyet, Cumhuriyet, and Aksam followed every significant find—from mosaic floors in geometrical patterns to ancient ceramic fragments and Ottoman-period coins.

Even a 19th-century Turkish fountain was unearthed and documented, though left buried again due to structural concerns. Schneider noted that its construction had damaged parts of the earlier Byzantine propylon.

The project transformed Hagia Sophia’s garden into an open-air museum. Artifacts including columns, capitals, and architectural blocks were displayed in the courtyard. Later, many of the smaller items—such as terracotta bowls, glass goblets, and intricately inscribed plaques—were transferred to the Istanbul Archaeological Museum and later to Hagia Sophia Museum’s own collections.

These finds formed the foundation of the current museum layout surrounding the monument, giving visitors today a glimpse of the complex, layered history beneath their feet.

Although the dig concluded in 1939, Schneider’s detailed reports and the remaining artifacts continue to inspire new research and public fascination—offering timeless testimony to the imperial, religious, and architectural layers buried beneath Hagia Sophia.