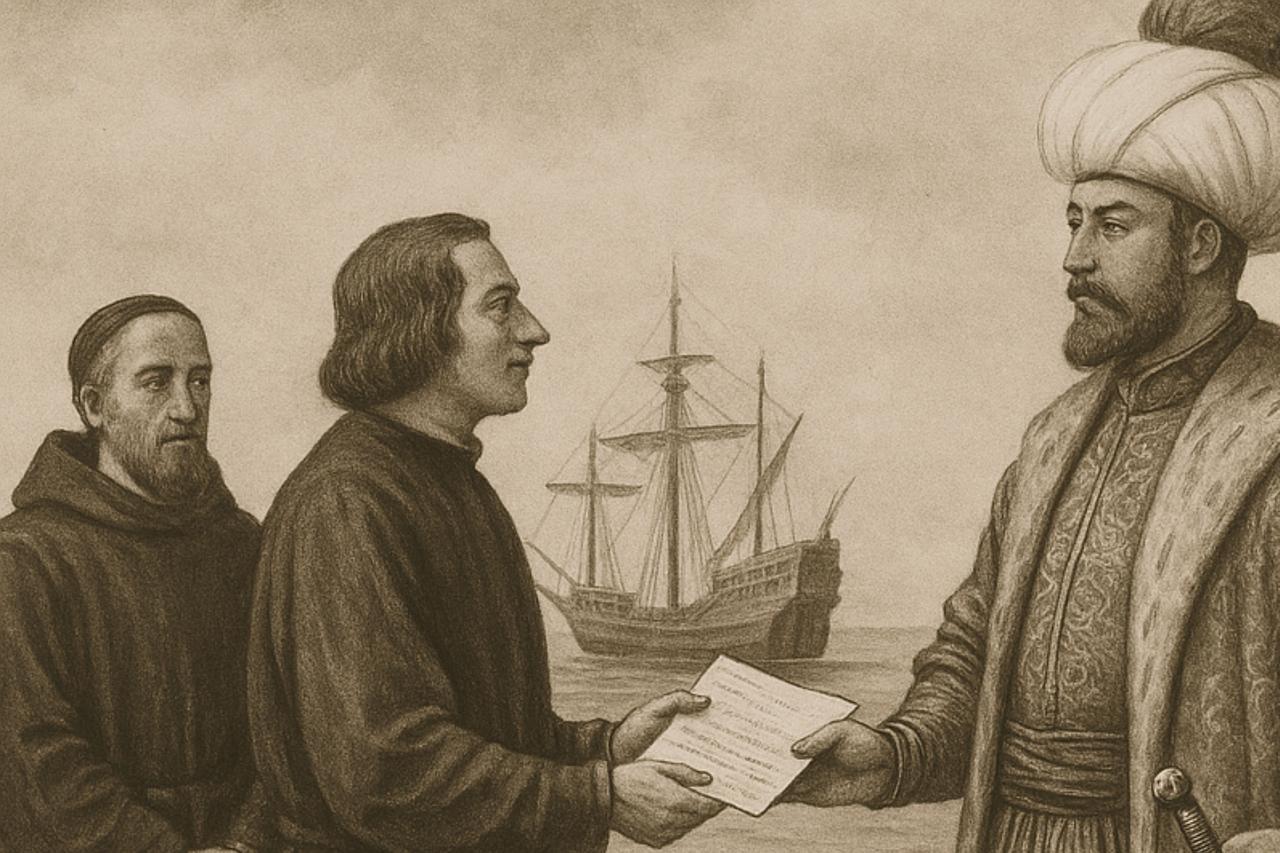

Long before Christopher Columbus sailed under the Spanish crown, he reportedly turned to Sultan Bayezid II of the Ottoman Empire to seek support for his westward voyage.

According to research by Zeynep Dramali and Hans Joachim Kissling, this request—largely forgotten in mainstream narratives—might have altered global history had it been accepted.

The story begins in 1484, a few years before Columbus's famous journey in 1492. After being turned down by the Portuguese crown, Columbus, then a struggling mariner, approached the Ottoman court.

At the time, Sultan Bayezid II was engaged in various internal and external conflicts, including tensions involving his brother, Cem Sultan.

A European priest reportedly accompanied Columbus to present his petition to the sultan, asking for ships to sail westward and discover new lands in the sultan's name.

However, historical accounts suggest the Ottoman court either declined or ignored the request, although the exact response remains unknown.

Born in 1451 in Genoa, Italy, Columbus was influenced by various seafaring traditions across Europe. After settling in Portugal, a dominant naval power in the 15th century, he traveled to Iceland in the late 1470s. There, he encountered tales of Viking explorer Leif Eriksson, who is believed to have reached the American continent in the 11th century.

Inspired by the idea of sailing west to reach the East, Columbus returned to Lisbon and began studying medieval travel accounts, including the memoirs of Marco Polo and stories of Saint Brendan’s legendary Atlantic voyage from Ireland.

Despite years of lobbying, Columbus's attempts to gain royal sponsorship failed throughout Europe. His 1484 petition to the Portuguese king was declined. After the presumed refusal from Sultan Bayezid II, Columbus briefly entered the resin trade to make ends meet. Even the Spanish monarchs initially rejected his proposal in 1486, after a special committee deemed his plan unfeasible.

Still undeterred, Columbus prepared to appeal to the monarchs of England and France. Just as he was about to leave Spain in early 1492, his supporters managed to convince the Spanish crown to reconsider. In August of that year, Columbus departed with three ships and landed in the Bahamas two months later, though he believed he had reached the eastern fringes of Asia.

Columbus never realized he had discovered a new continent. Believing he had reached Asia, he envisioned his mission as part of a larger goal to reclaim Jerusalem from Muslim control. Even after multiple voyages, ending in 1502, he died in 1506, unaware of the true scale of his achievement.

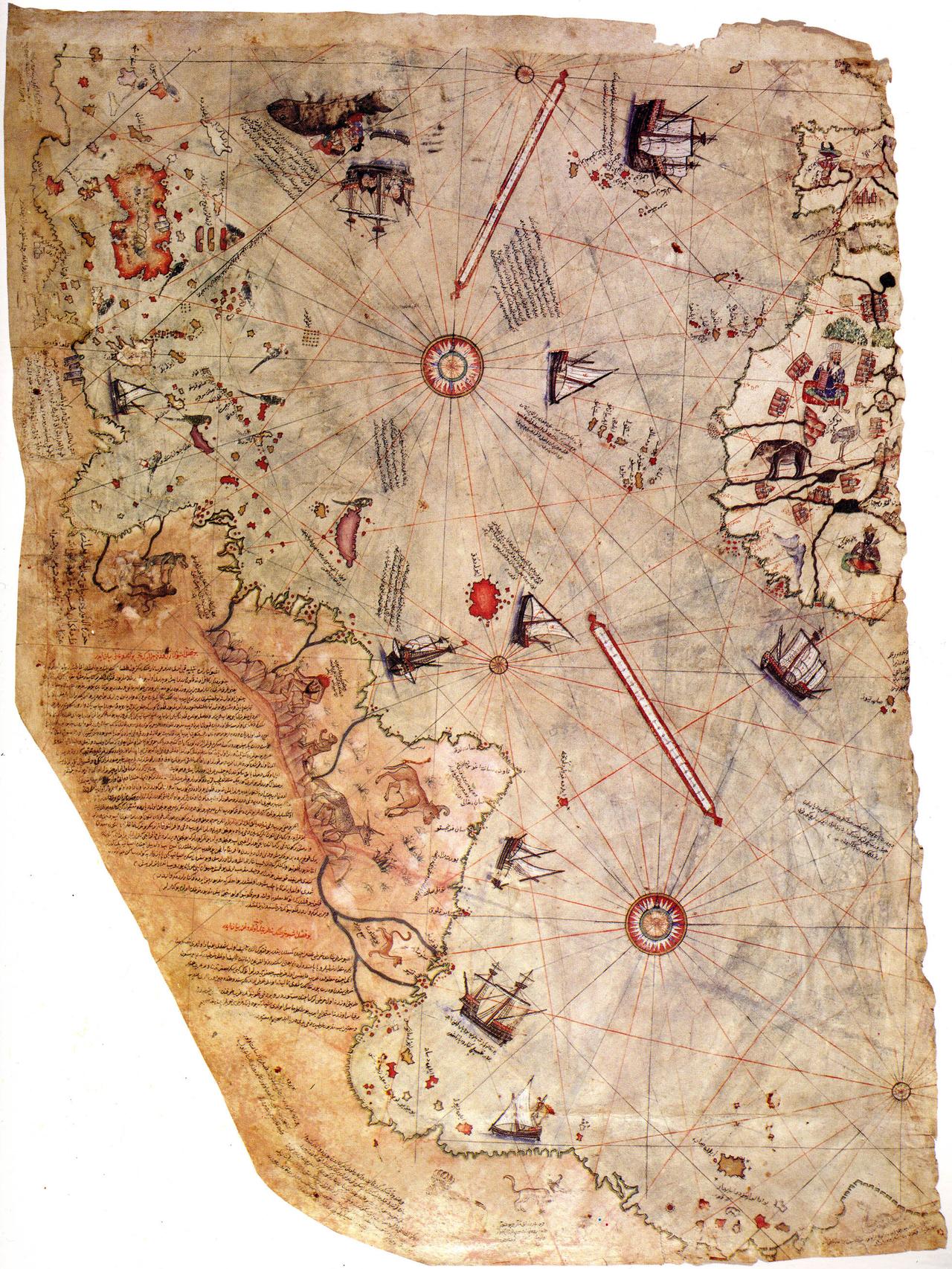

The Ottoman Empire, however, did not remain uninformed about the discovery of the Americas. The renowned Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis learned of Columbus’s findings from a Spanish sailor captured by his uncle, Kemal Reis. This sailor had reportedly accompanied Columbus on three of his journeys.

In 1513, Piri Reis included these accounts in his famous world map, inscribing on the chart, “In the year 1492, a Genoese infidel named Kolonbo discovered these lands. He had found a book saying there were islands and mines at the edge of the Western Sea...”

This map became one of the earliest depictions of the New World from an Islamic perspective, reflecting how the Ottomans slowly began to absorb knowledge of global exploration into their own cartographic and scholarly traditions.

![Western and Eastern hemispheres from Tarih ul-Hind il-Garbi (The History of the Western Indies), Constantinople: Ibrahim Muteferrika, [1730]. Spread [94], rebound in blind-tooled morocco, likely 20th-century American. (Photo via princeton.edu)](https://img.turkiyetoday.com/images/2025/6/24/what-if-america-had-been-ottoman-forgotten-proposal-from-columbus-to-sultan-bayezid-i-3203362_202506241521_4.webp)

The Ottomans eventually compiled more detailed works on the New World. In the late 16th century, an anonymous author penned Tarih ul-Hind il-Garbi (The History of the Western Indies), offering a comprehensive account of the European conquest of the Americas from Columbus to Pizarro.

Though mostly adapted from Italian sources, it marked the first significant attempt in Ottoman literature to chronicle the age of discovery in the Western Hemisphere.