Speaking to Izmir Art, Ridvan Golcuk, Director of Yasar Museum, said the theft of French Royal jewels from the Louvre in broad daylight revealed deeper vulnerabilities.

On Sunday, Oct. 19, intruders reportedly broke a window and entered the Apollo Gallery around 9:30 a.m.

The hall—home to the French Crown Jewels—was the specific target. Golcuk argues that the incident points less to a cinematic, high-tech plan and more to basic, human, and systemic failures inside institutions that should be the most secure.

Golcuk recalled the April 15, 2019, Notre Dame fire, where the alarm system produced a code that staff could not interpret. A guard checked the wrong place, and precious minutes were lost.

For him, this illustrates how an expensive system collapses if the people running it are not trained to understand and act on it.

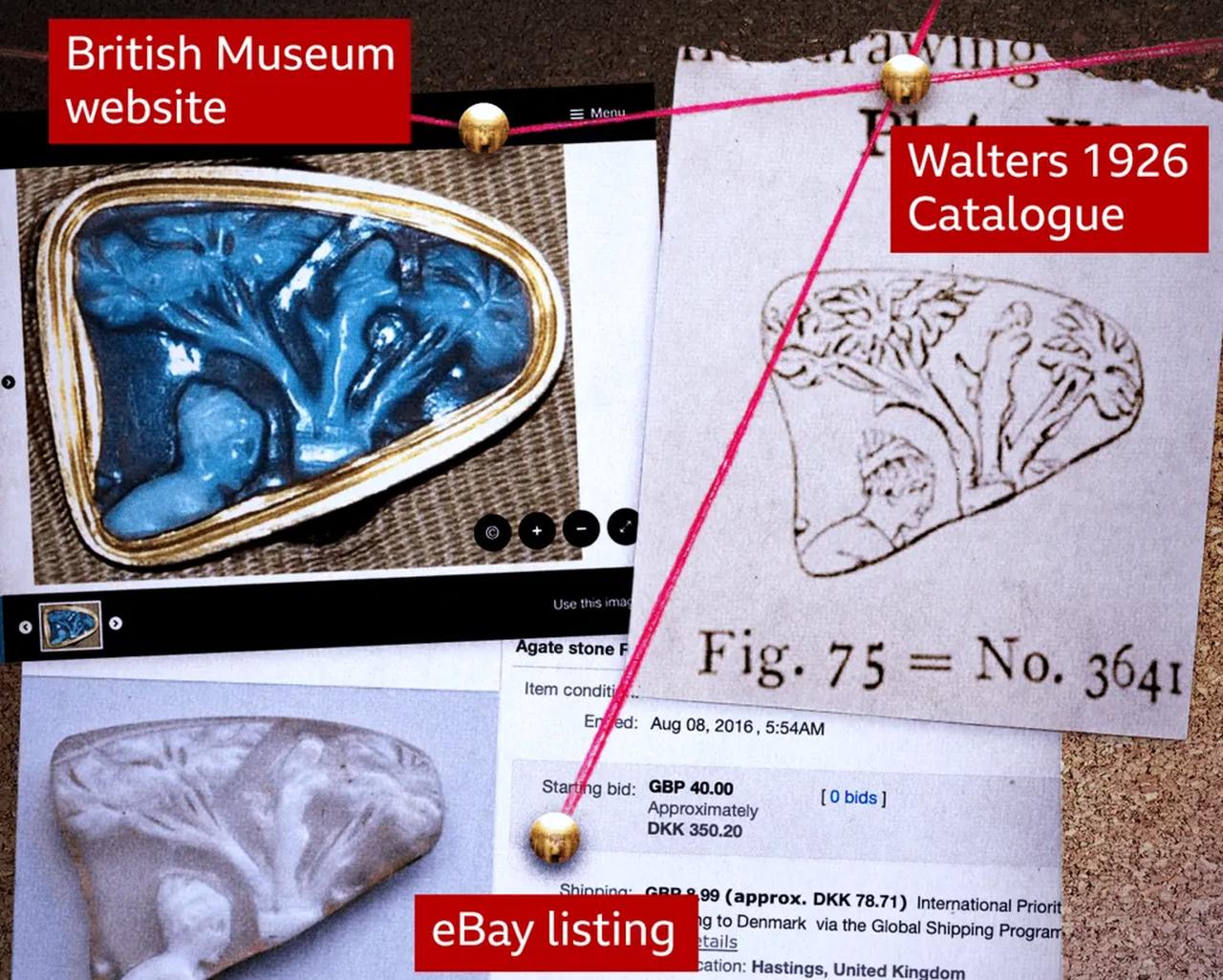

He pointed to the British Museum case, where a senior curator allegedly removed and sold items online for years without detection.

The biggest risk, Golcuk said, sometimes “walks the corridors” with a staff badge—showing why internal controls must be layered and relentless, not just aimed at doors and visitors.

Golcuk noted that closures and budget cuts during the pandemic brought a wave of thefts. In the Netherlands, Van Gogh’s "Parsonage Garden at Nuenen in Spring" was stolen from the Singer Laren Museum, and a Frans Hals work vanished from another.

In Germany, the Dresden Green Vault—a royal treasury—suffered a major jewel heist after criminals disabled systems and cut through bars. The pattern, he said, shows how thinly stretched teams can invite attacks.

The Louvre case, Golcuk suggests, may reflect “alarm fatigue”—when repeated false alerts make staff slow to respond.

Even advanced sensors and AI-enabled cameras, he argues, cannot replace motivated, drilled teams who know exactly what to do when seconds matter.

Because the Apollo Gallery holds national symbols—pieces tied to Napoleon and the Second Empire—the theft, he says, cuts beyond money.

In a post-colonial climate, major European museums face anger over contested collections, which can make them lightning rods. He warned that some may view theft as a form of “justice,” a risk that security planning cannot ignore.

Mega-museums now function like high-volume visitor machines.

Golcuk says vast crowds and nonstop service demands fragment attention, wear down staff, and make comprehensive control harder.

He argues that protection—the core mission—can slip behind throughput and satisfaction metrics unless leadership resets priorities.

For Golcuk, the Louvre heist mirrors a broader European drift away from “hard security” basics in favor of soft-power assets like culture and tourism.

He calls for urgent reviews of simple controls, crowd management, and the reputational risks tied to colonial-era holdings.

“The incident at the Louvre is not only a warning for France but for the whole of Western European museology,” Golcuk told Izmir Art.

“From basic security measures to managing the pressures of mass tourism, and most importantly, confronting the negative image created by the colonial past—all these issues urgently need to be addressed.”