Educators, authors and media specialists meeting in Istanbul say children’s shrinking attention spans and fast-paced digital media are starting to reshape how young people read, learn and engage with stories, and they warn that profit-driven platforms are making deep, focused reading much harder to sustain.

The concern dominated discussions on the sidelines of the TRT International Children’s Media Summit 2025 in Istanbul, where experts speaking to Anadolu Agency underlined that digital platforms now sit at the heart of childhood, while families, schools and the media industry share responsibility for how this new environment develops.

Warren Buckleitner, a psychologist and technology expert, said today’s children are growing up in a media landscape that older generations never experienced, because there is now virtually unlimited choice and constant stimulation across screens.

He compared this environment to “a theme park … in your backyard,” where digital content is always available and rarely filtered before it reaches young viewers. Unlike earlier eras, when children often had just a few television channels to choose from, this abundance now requires adults to step in and guide what children actually watch and read.

Buckleitner stressed that someone needs to curate children’s media use, using the term “curate” to describe the careful selection and organisation of content that fits a child’s age and development. He argued that it is no longer enough for parents or caregivers to hand over a tablet and walk away, and said adults should think about how children spend what he called their “limited childhood minutes” and whether the material they consume really helps them grow.

Despite these pressures, Buckleitner noted that technology itself, especially artificial intelligence, often shortened to AI, could play a constructive role if people use it responsibly. He pointed to the potential for AI tools to adapt school materials to each child, so that lessons can become more engaging without losing depth or complexity.

He suggested that AI systems could tailor curricula to individual needs and help children move through subjects at their own pace, which might support more meaningful learning instead of pushing them to jump quickly from one piece of content to another.

However, Buckleitner underlined that the way digital media makes money frequently runs against children’s interests. He described “the economic model” as the biggest problem and noted that online content is often designed to chase views and clicks rather than to serve developmental goals.

Referring to the late American children’s broadcaster Fred Rogers, he repeated the warning that “There’s a sacred ground between the child and the camera. … Commercial agendas should not be part of that,” and he linked this idea to current platforms which depend on advertising and engagement metrics.

Michael Milo, founder of Muslim Kids and its platform Muslim Kids TV, voiced similar concerns about the way algorithm-driven and short-form media affect young audiences. He used “algorithm-driven” to refer to systems that automatically select what appears next on a screen by tracking viewing patterns, while “short-form storytelling” describes very brief, fast-cut videos that often encourage constant swiping.

Milo said this kind of content can weaken children’s ability to focus if adults do not step in early. Speaking about digital media, he noted that “There’s good in it and there’s bad in it,” and added that people “have to work very hard to bring the good in it out and minimize the bad in it.”

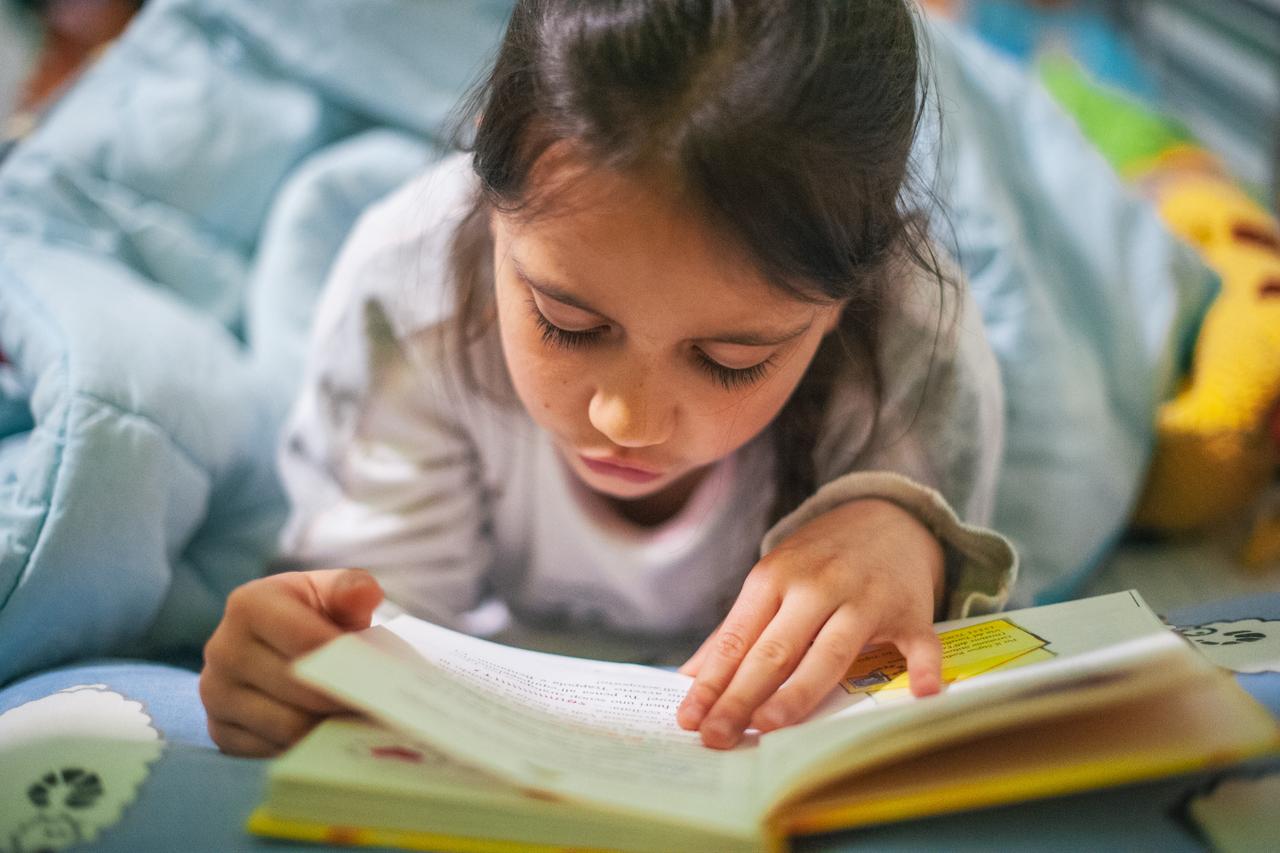

He stressed that traditional reading, outdoor play and active family involvement still play a central role in healthy development, and he argued that parents need to stay closely involved in how their children interact with screens. According to Milo, balanced exposure can help preserve both attention and imagination, rather than allowing fast-paced clips to push slower forms of storytelling aside.

Drawing on his experience with Muslim Kids TV, Milo said that when families introduce their children to slower, more thoughtful content at a very young age, they tend to adapt well and stay engaged even if the material does not follow a rapid-fire style. By contrast, he warned that early exposure to harmful or highly overstimulating media makes it much harder to shift children later towards calmer, more reflective stories and programmes.

Both experts also addressed widening global debates over how to regulate children’s online environments, including new digital rules in countries such as Australia and Türkiye. They linked these discussions to concerns that the current digital ecosystem leaves too many decisions to companies and families who may not be fully equipped to deal with complex platforms.

Milo argued that strict regulation may become necessary where voluntary measures have fallen short. He said, “The big media companies are not regulating themselves. They’re profit-driven,” and he added that many families and children do not always have the tools or knowledge they need to make informed choices about what they see online.

At the Istanbul summit, these warnings came together in a shared message: children now grow up in a world where digital media shapes much of their everyday experience, and the way societies respond will strongly influence how the next generation learns to read, think and connect with stories.