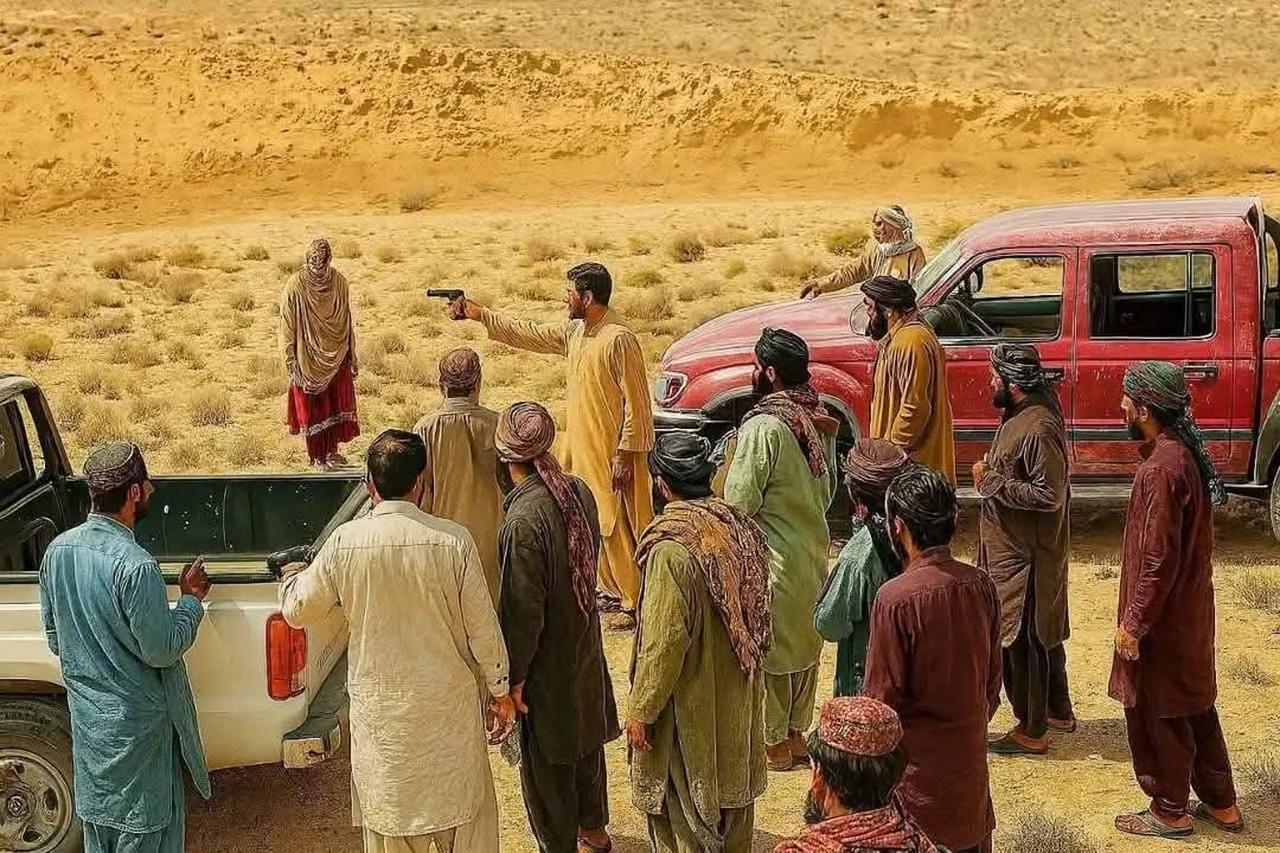

In July 2025, a deeply disturbing video circulated across social media in Pakistan. It showed a young couple being pulled from vehicles and shot at point-blank range in a barren desert area, believed to be in Balochistan.

The footage, graphic and haunting, captured not only a brutal murder but also the chilling silence of those watching, a silence that reflects the social acceptance of “honor” killings in parts of South Asia.

“You are only allowed to fire at me, nothing else,” she said, before the man raised a pistol and shot her at close range.

Balochistan Chief Minister Sarfraz Bugti responded to the public outcry by confirming the incident. “The law will take its course in this heinous matter.”

The couple’s identities were confirmed, and state authorities were called to act swiftly. Yet the incident mirrors countless other similar cases that never reach public attention.

Honor killing, the murder of a family member, usually a woman, for allegedly humiliating the family, is not codified in religion.

It is a practice inherited through generations of tribal codes, particularly in areas where male guardianship over women’s autonomy remains unchallenged.

In Afghanistan and Pakistan, such customs embed the concept of honor into family and community reputation, often placing the burden entirely on women’s behavior.

While these killings are criminal under national law, they are often justified in the eyes of the community as acts of moral correction.

In many tribal areas, traditional justice systems like jirgas and shuras often offer implicit or explicit approval.

These systems operate in parallel to the official judiciary, especially in rural regions where state governance is weak. This cultural insulation makes prosecution difficult and perpetuates impunity for perpetrators.

Despite global awareness, honor killings remain a present danger.

Many such incidents are unreported or misclassified as domestic disputes. However, even among the recorded cases, the numbers remain troubling.

In Pakistan, media and rights organizations document hundreds of honor-related murders yearly. According to the Pakistani NGO SSDO, there were 225 honor killing reports in Punjab alone in 2024, but only two convictions were secured nationally for these cases. Overall, GBV filings surpassed 32,600 for the year.

In Sindh province alone, at least five women were killed within 36 hours early in 2025, underscoring the rapid recurrence of such violence even in urban regions.

In Afghanistan, while data is sparse, UNAMA reported up to 240 honor killings in earlier years. Institutional collapse since 2021 makes current tracking difficult. These crimes remain largely unpunished.

Bangladesh sees fewer reported honor killings, yet high rates of child marriage (over 50%) pose related risks, as per UNICEF‑related child marriage statistics, 2025.

Though direct cases are rare, scholars warn that patriarchal control persists in certain rural localities.

The persistence of honor killing lies in the entanglement of legal loopholes and cultural acceptance.

In Pakistan, the 2016 Criminal Law Amendment closed the legal forgiveness loophole that once allowed family members to pardon the killers. However, implementation is uneven. In rural courts, pressure to reconcile often leads to informal settlements, keeping the killer within the community.

In Afghanistan, the state’s disintegration post-2021 has meant near-total loss of protection for women. Legal safeguards are either unenforced or nonexistent, and cultural structures dominate decision-making. Women’s shelters have been shut down, and reporting crimes themselves has become dangerous under the current governance.

These structural gaps are reinforced by a cultural narrative that equates female honor with family status. In such societies, male guardianship is normalized, and deviation from expected roles is perceived as dishonor, often with deadly consequences.

Eradicating honor killings requires not only legal reform but cultural transformation. While passing laws is essential, social intervention is just as critical. Education plays a foundational role, especially in rural areas where gender roles are deeply entrenched. School-based gender sensitivity programs, religious reinterpretation of justice and honor, and the inclusion of women in tribal councils are potential steps toward long-term change.

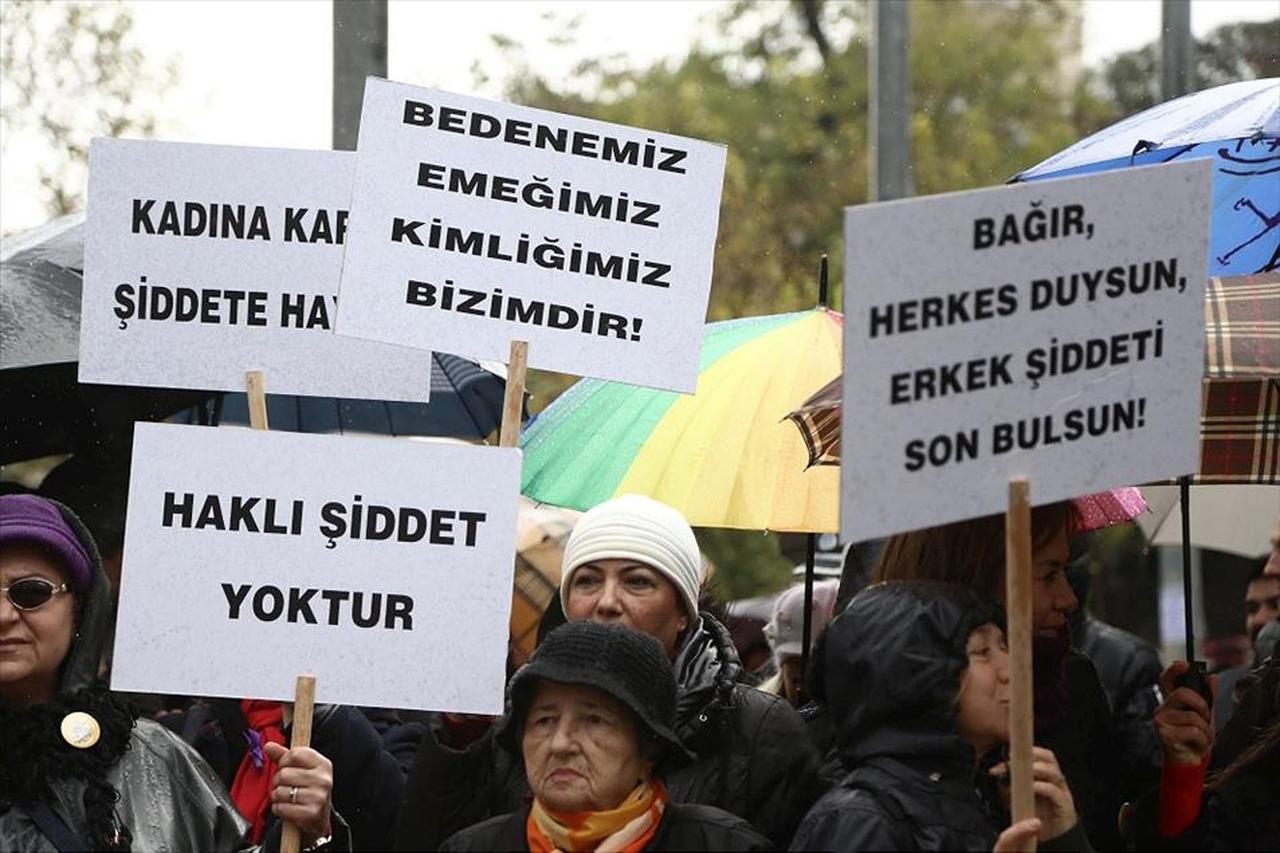

In Türkiye, similar issues around gender-based violence have sparked reforms in the justice system, such as the expansion of women’s shelters and campaigns like No to Violence Against Women.

Türkiye's experience shows that coordinated action between civil society, state institutions, and media can shift narratives, even in conservative settings.

Media must play a stronger role in South Asia, too, not just reporting violence when it goes viral, but proactively telling stories of survivors, documenting justice gaps, and holding institutions accountable.

Honor killing is often framed as a cultural issue, but at its core, it is a human rights violation. It reflects a value system where women’s lives are conditional on obedience, where men are entitled to judge and punish, and where community reputation is worth more than life.

This is not tradition. It is normalized violence. While the recent Balochistan case has rightly attracted attention, public focus mustn't fade once the headlines do. Behind every reported case lie dozens of unspoken stories buried by fear, shame and inherited silence.