Lisa Morrow is a sociologist, author, and travel writer originally from Australia, who has lived in Istanbul and other parts of Türkiye for over 15 years.

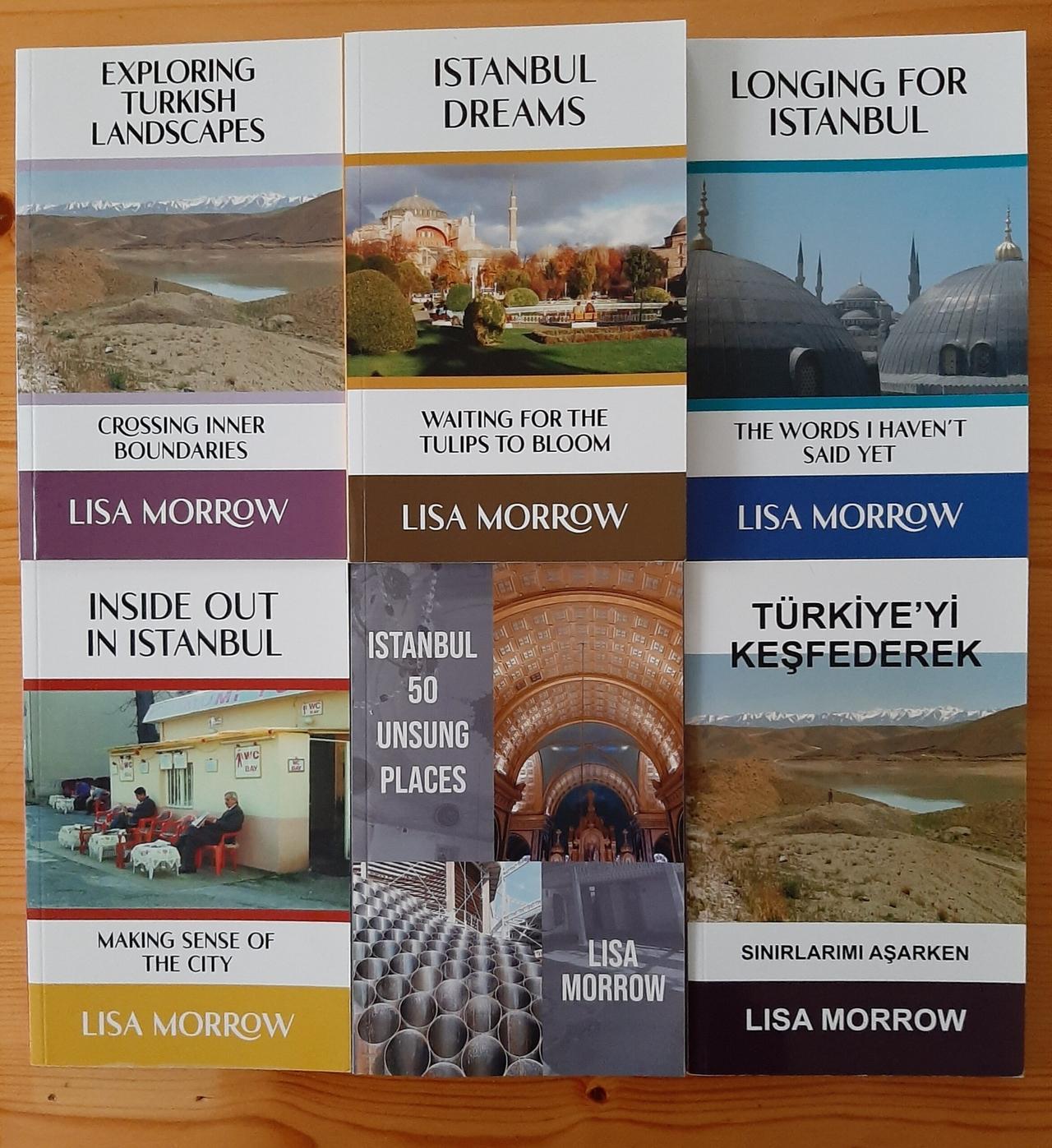

She is the author of the book "Inside Out in Istanbul." She has written several books that examine the city’s lesser-known places, everyday social habits, and the regional variations that shape life across Türkiye, while also contributing regularly to international publications on the city’s social complexity and daily experience.

Morrow first came to Istanbul by coincidence rather than intention, arriving after a series of short moves across Europe that led her to Greece, the Aegean and ultimately Türkiye. Instead of relying on familiar images, she learned Istanbul through daily routines, conversations and practical encounters.

Over time, she learned the city's rhythms, contradictions and unwritten rules. She also recognized that she moves through Türkiye as a foreign woman in a place where family networks, expectations and regional differences significantly structure social life.

During our conversation, she explained how she studies the ways people relate to one another, how certain habits have become part of her own behaviour, and how long-term life in Türkiye shifts her sense of belonging.

In her first months in Istanbul, Lisa Morrow realised that she would learn more from ordinary interactions than from any preconceived framework, and many of the moments that stayed with her came from watching how people move through their daily lives.

She explained that she rarely reacts instantly to new situations because she needs time to absorb what is happening, saying, “I first get a lot of information and then I look for the right words to write about it,” a habit that shaped the way she approached the city.

This slow attention made her notice the small details that form the rhythm of daily life, whether it was how people greet one another, how neighbours establish a sense of familiarity, or how strangers shift seamlessly into conversation on buses, ferries, or in shops.

Early on, she became conscious of the social codes that guide behaviour in public spaces, even when people do not acknowledge them directly.

She describes observing some women on long-distance buses who remain on the phone with a parent, family member, or partner for most of the journey, not out of boredom but to signal that they are never entirely alone.

“They are constantly letting someone know where they are and who they are with,” she says, which revealed to her how much everyday life rests on visible connections to family and community. This awareness helped her understand why Istanbul often feels both crowded and intimate, since people move in ways that reinforce proximity rather than distance.

These repeated encounters gradually exposed the unwritten rules that structure social life. Morrow recalls how quickly people step in to offer help, whether it involves finding an address, navigating a bureaucratic office, or managing a crowded space, noting that this reflexive concern for others can feel overwhelming to someone who grew up in a more reserved environment.

At the same time, she observed how insistence around food, hospitality and shared routines functions as both politeness and expectation. She explained that in Türkiye, “You must have some more, you must eat,” is a natural part of conversation rather than a literal command, and learning to interpret these gestures helped her understand the city’s social texture. In fact, she has also embraced habits like insisting on extra food and taking shoes off before entering a household over the years.

These insights emerged not from dramatic encounters but from the repetition of small moments that revealed how people relate to one another. Morrow reflects on this process by saying, “I tend to understand things a lot better by paying attention to the details people think do not matter,” and it is these details that shaped her earliest sense of Istanbul and then Türkiye.

As Morrow spent more time in Istanbul, she began to understand that her position as a foreign woman placed her both inside everyday life and slightly outside the networks that organise it. This form of mobility allowed her to cross social boundaries with ease while also reminding her that she did not fully belong to the structures that guide most relationships in Türkiye.

She explains that locals often respond to her cultural unfamiliarity with patience, saying, “I am forgiven because I am not expected to know how you do things." This dynamic grants her access to conversations and spaces that might be more tightly defined by customs for someone who grew up within them.

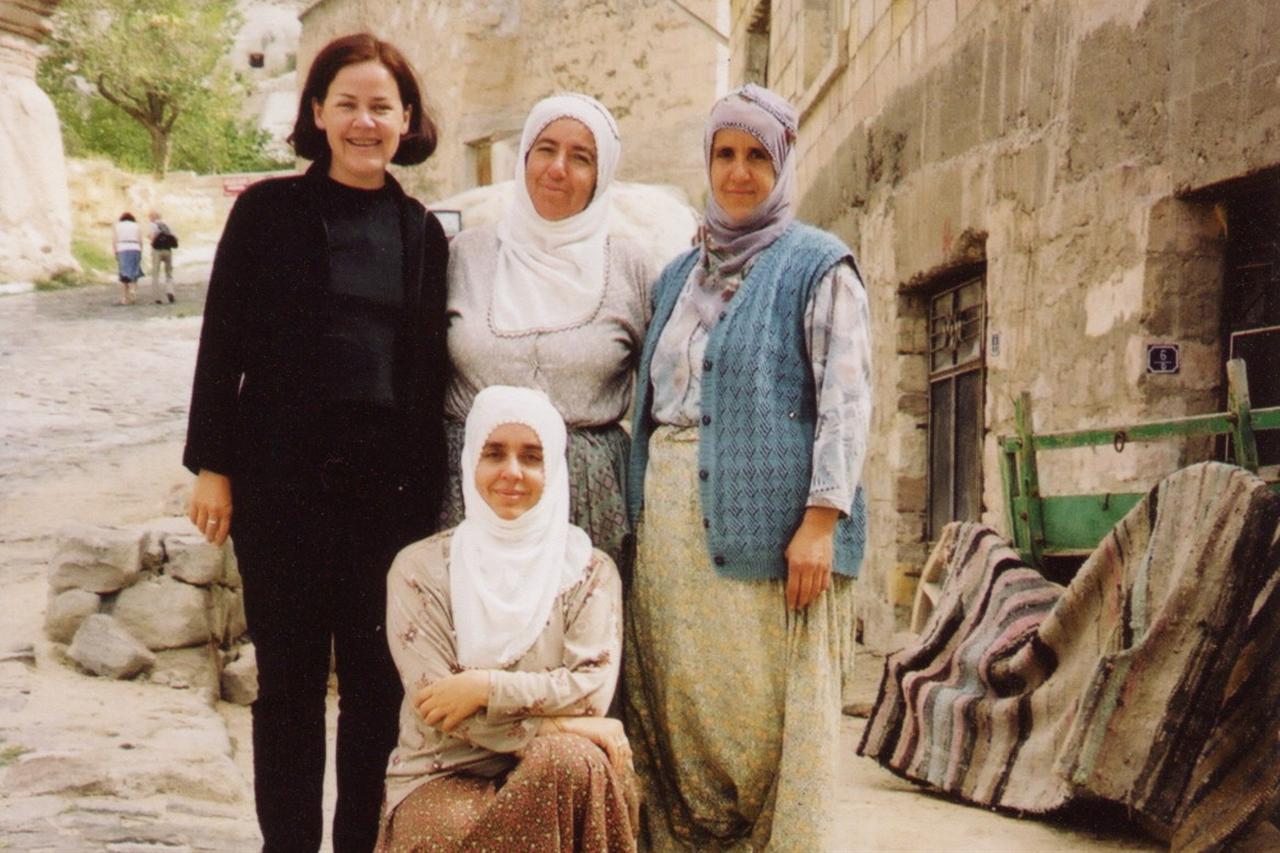

This position became especially visible during her early experiences in women’s gatherings. She recalls attending a henna night (kina gecesi) in a Turkish village where hundreds of women filled the space, most of them wearing headscarves and hand-knit cardigans, while she stood out immediately in fitted trousers that marked her as the only foreigner in the group.

Although the attention unsettled her at first, she remembers how quickly the women welcomed her, included her in their conversations, and treated her with warmth. The combination of curiosity and generosity revealed a form of hospitality that does not require complete cultural understanding but instead rests on an instinctive willingness to bring others into the event.

While continuing to navigate daily life in Istanbul, she noticed that she blended into her surroundings more than she expected. Her clothes come from local shops, her haircut follows local styles, and her routines mirror those of the neighbourhoods she moves through.

She jokes that the only detail that consistently reveals her foreignness is “the way I walk, because I walk fast,” a habit that stands out in a city where people often move in groups and at a pace shaped by conversation, companionship, and shared errands.

These moments made her aware of how easily familiarity can grow, even when certain forms of belonging remain outside her reach.

Her sense of distance becomes sharper when she reflects on the central role of family in Türkiye, where social life is often organized around parents, siblings, cousins, and in-laws whose presence extends into daily decisions, celebrations, and obligations.

She notes that “everyone has family first,” and although she feels at home in Türkiye, she also recognises that she is not woven into these inherited networks and instead builds her life through friendships that provide closeness without the depth of long-established ties.

The contrast becomes especially clear when she returns to Australia, where she realises how much she has absorbed from Türkiye, from the ease of talking to strangers to the expectation that social interaction will unfold generously and without hesitation.

Through these overlapping experiences, Morrow has come to inhabit a position that is shaped by long-term familiarity yet never fully absorbed into the structures that define everyday life for those who grew up within them, creating a shifting and situational sense of belonging that depends on context rather than fixed identity.

As Morrow travelled outside Istanbul and encountered people whose daily routines unfolded far from the city’s more familiar districts, she began to understand how misleading it can be to treat Türkiye as a unified cultural landscape.

She notes that newcomers often believe they understand the country after spending time in places like Cihangir or Sultanahmet, but she argues that “certain parts of Istanbul do not really represent Türkiye,” because their international atmosphere allows visitors to live comfortably without ever learning the deeper logic that shapes social life elsewhere.

Her years in Kayseri in the early 2000s offered the clearest early lesson in this regional difference. She describes the city back then as “a provincial town where life revolved around neighbours’ houses, long picnics and endless meals." Eid al-Adha (Kurban Bayram) became especially revealing, not through abstract symbolism but through practical moments that showed how traditions function in everyday settings.

She recalls a neighbour apologizing because her husband could not come to the door, explaining that “he and his brother bought a cow for Eid and he is on the balcony dividing all the packets for everyone,” an image that helped her see the festival not through the distant lens of ritual but through the concrete work of preparing and distributing meat as an act of responsibility and care.

She remembers sitting on mini-buses during the holiday and noticing people carrying packages of meat, which led her to realise that “people focus on the killing, but the real meaning comes after, in where the meat goes and how it connects people.”

Her experiences with university students further revealed how regional norms shape young women’s lives in ways that cannot be understood through generalisations. She and her husband once travelled with a group of students, many of whom came from towns where family expectations remained strong. She later learned that some lived in dormitories where “the door was locked at seven o’clock,” not as punishment but as reassurance to parents who would not have allowed their daughters to study away from home without strict supervision.

Regional variation also reshaped her understanding of public expression and personal identity. She recalls attending a religious gathering for a friend’s mother in Istanbul and arriving with bright lipstick and a headscarf, later discovering that makeup was considered inappropriate for the occasion.

Another woman arrived in a sheer silk scarf, a choice that combined respect for tradition with a quiet insistence on her own secular identity. “She was following the custom her way,” Morrow says, which taught her that clothing cannot be interpreted through fixed categories, since meanings shift across regions, families, and generations. Experiences like this helped her recognise how easily outsiders mistake appearance for belief, and how regional context determines which interpretations make sense.

Morrow also reflects on how different the expat landscape looks today compared with the foreign communities she first encountered in Türkiye.

She explains that the people who arrived in the early 2000s, the roles they took, and the circumstances that brought them here have changed so dramatically that they no longer form a recognisable group.

When she first lived in the country, the absence of Facebook groups, online forums, or easy digital networks meant that newcomers depended on one another for support, information, and company.

In the 2010s, she returned with “very good Turkish friends” already in place because the relationships she formed earlier had shaped her sense of orientation more than her expat circle.

Her early years were defined by a strong Anglophone presence, with Australians, British citizens, Americans, and New Zealanders working primarily as English teachers or as nannies for families who valued native speakers. Morrow remembers how many schools and colleges promised work permits that never materialised, pushing people into cycles of tourist visas and quick border runs.

She also recalls the economic pressures that led young Americans to seek opportunities abroad. “A lot of them graduated with debt and no job prospects,” she says, and Türkiye appeared to offer a solution during a difficult period.

Over time, the makeup of the foreign population shifted as educational institutions lowered salaries, recruited highly trained teachers from Iran or Turkmenistan who accepted lower pay, and replaced Anglo nannies with legal domestic workers from Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, or Uzbekistan.

Morrow points out that these changes altered the cultural texture of the expat scene, explaining that “our paths do not cross because our needs are different,” since many newer arrivals come from regions affected by war, economic instability, or displacement and therefore experience Türkiye through circumstances far removed from those of earlier groups.

Today, she sees large communities of Ukrainians, Russians and Syrians whose presence is shaped more by necessity than by the curiosity that motivated previous generations of foreigners.

On the other hand, the contrast between her own life and the world of high-income corporate expats also became more pronounced over time. She describes how some foreigners live with drivers, housing allowances, and professional fixers who manage every administrative task, creating a bubble that insulates them from the realities of urban life.

“I live here. This is my home. It is not temporary,” she says, emphasising that her Turkish language skills and sense of belonging emerged from negotiating with plumbers, municipal officers, and hospital staff rather than from a lifestyle protected by corporate resources. These interactions formed the backbone of her long-term attachment to the country.

Her closest Turkish friends eventually gained a deeper appreciation for the challenges she faces as a foreigner. When she explained the difficulties of obtaining residency documents or navigating contradictory bureaucratic instructions, one friend responded, “I am never moving to another country after listening to you,” a comment that revealed how foreignness can appear more burdensome than glamorous.

Morrow approaches travel writing with a strong awareness of how Türkiye is often flattened into familiar images, and she rejects the idea that the country can be captured through the limited set of symbols that dominate mainstream narratives.

She explains that many articles about Türkiye repeat the same clichés not because they are accurate but because editors expect them, noting that “all they want is confirmation of what they already believe,” a pattern that frustrates writers who try to present complexity rather than simplified impressions. Her own experiences pushed her to resist these expectations, since she knows that Türkiye’s diversity cannot be reduced to a handful of predictable themes.

Her reading of older travel literature made the problem especially clear. She mentions how 19th-century writers often described spaces they could never have entered, including bathhouses (hammams) or women’s quarters, producing vivid but entirely fictional accounts that continue to influence how outsiders imagine the region. “He never would have been to a hammam,” she says about well-known writer Edmondo De Amicis, pointing to the gap between literary fantasy and actual experience.

She also criticizes modern articles that amplify exotic elements while ignoring the realities of daily life. She recalls reading pieces that focus on narrow stereotypes or repeat familiar tropes about Turkish food, cats, "mandatory" headscarves, hospitality, or mysterious traditions, as though the country exists primarily to satisfy Western imagination.

She finds this approach reductive, saying, “I do not see Türkiye as seductive or alluring in the way older travel writing does,” because such depictions erase the social complexity she encounters in her neighbourhood, on public transport or in conversations with ordinary people. For her, the problem is not the presence of difference but the insistence that difference must be packaged in a specific, marketable way.

She also speaks about the visual stereotypes that dominate popular representations of Istanbul, particularly in districts like Sultanahmet, where visitors often assume that women wearing full black attire are Turkish, even though many come from Gulf countries.

She refers to this as a kind of “Disneyfication,” an image built not on observation but on expectation, and one that obscures the city’s internal diversity. These misconceptions reveal how quickly foreign observers read culture through fixed symbols rather than through the variations that define everyday life.

Morrow believes that depicting Türkiye honestly requires confronting these assumptions rather than indulging them, even if that makes her work harder to publish. “The popularity of those bog-standard pieces makes it harder to publish anything nuanced,” she says, acknowledging that the travel industry often rewards repetition rather than critical engagement.

Her reflections show how long-term life in Türkiye relies less on fixed narratives than on the slow accumulation of encounters that reveal how people organise their routines, negotiate expectations, and express identity in ways that rarely align with outside assumptions.

Her observations move across regions, households, and social circles, aiming to offer a picture of the country that comes from lived familiarity rather than from the symbols often repeated in travel writing.

In describing what she has learned, Morrow makes clear that understanding Türkiye requires attention to detail, context and the variations that shape daily experience, a process that continues to guide the way she writes and the way she interprets the place she now calls home.