Seagrass meadows in the Marmara Sea are broadly in good shape, according to scientists tracking eight coastal stations since May under the CAYIR-IZ monitoring project. Researchers flagged a single area where the endemic Mediterranean species Posidonia oceanica has recently retreated toward shallower waters, prompting further investigation.

Seagrasses—flowering, root-bearing plants often confused with algae—anchor coastal ecosystems. Scientists on the project underscored that they store carbon efficiently, help prevent shoreline erosion, and create nurseries for marine life. They also photosynthesize underwater, producing roughly 10–20 liters of oxygen per square meter each day. One expert noted that a seagrass meadow can host up to 40 times more organisms than adjacent bare sand, and said seagrasses “hold 35 times more carbon than forests.”

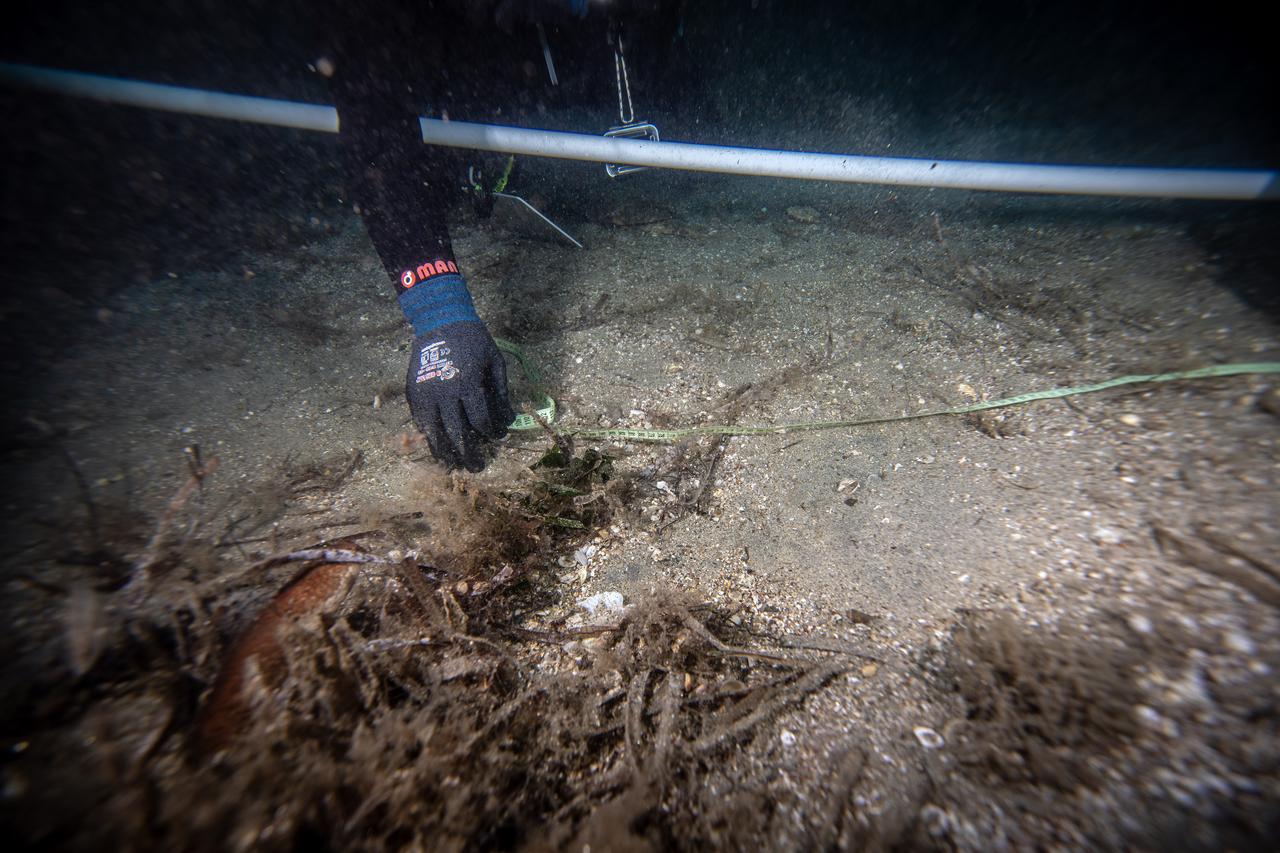

Earlier work led by Bandirma Onyedi Eylul University’s Faculty of Maritime Studies, with support from the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change, surveyed about 1,300 kilometers of Marmara’s coastline—including the islands—to map species diversity, distribution, density, and threats into a geographic information system. That research found four seagrass species across Marmara, with meadows providing habitat for many creatures, including “pinalar” (large fan-shaped mussels).

Built on those findings, CAYIR-IZ now monitors representative coastal sites across four seasons to assess ecological status and track pressures over time. The project, which has drawn public attention and support from Emine Erdogan, aims to restore damaged pockets of the sea and promote integrated, science-based management.

Project scientists explained that water clarity sets meadow depth limits. In the Aegean and Mediterranean, stronger light penetration lets meadows grow to around 40 meters; in Marmara, lower clarity caps them at roughly 7–8 meters. They added that more than 60% of Marmara’s shorelines still host seagrass, while stretches from Silivri to Gebze and the far north of Izmit Gulf currently do not, due to pollution and coastal interventions.

Researchers linked recent stress on meadows to recurring mucilage—thick organic sea slime—observed heavily in past years and reported again in September–October. They said this “new period” of mucilage may be among factors behind localized declines, which they will verify with samples and seasonal comparisons.

After the second round of dives, the team reported that overall meadow health looks good, but Posidonia oceanica retreated at one station. “From the deepest limit we recorded three months ago, the endemic Posidonia oceanica has moved upward by more than four meters,” said Associate Professor Ugur Karadurmus.

“Shifting from 9 meters to a shallower zone narrows its cover, squeezes the habitat, and calls for targeted protection strategies.” He added that reduced light penetration—driven by turbidity and pollution—may be the likely cause, though laboratory work will confirm the drivers.

Professor Mustafa Sari stressed that safeguarding meadows also protects “pinalar,” a key Marmara species, and tied the effort directly to the sea’s future, saying, “If we are to keep Marmara alive, we must also protect and manage the seagrass meadows.”

With data logged every three months, the team aims to pinpoint where meadows are pushing seaward (a positive sign) or pulling back toward shore (a negative one), then channel those findings into action. “In critical, sensitive areas, we will secure their future with protection policies,” Karadurmus said, noting that the project is designed not only for Marmara but as a model with global relevance for coastal conservation.