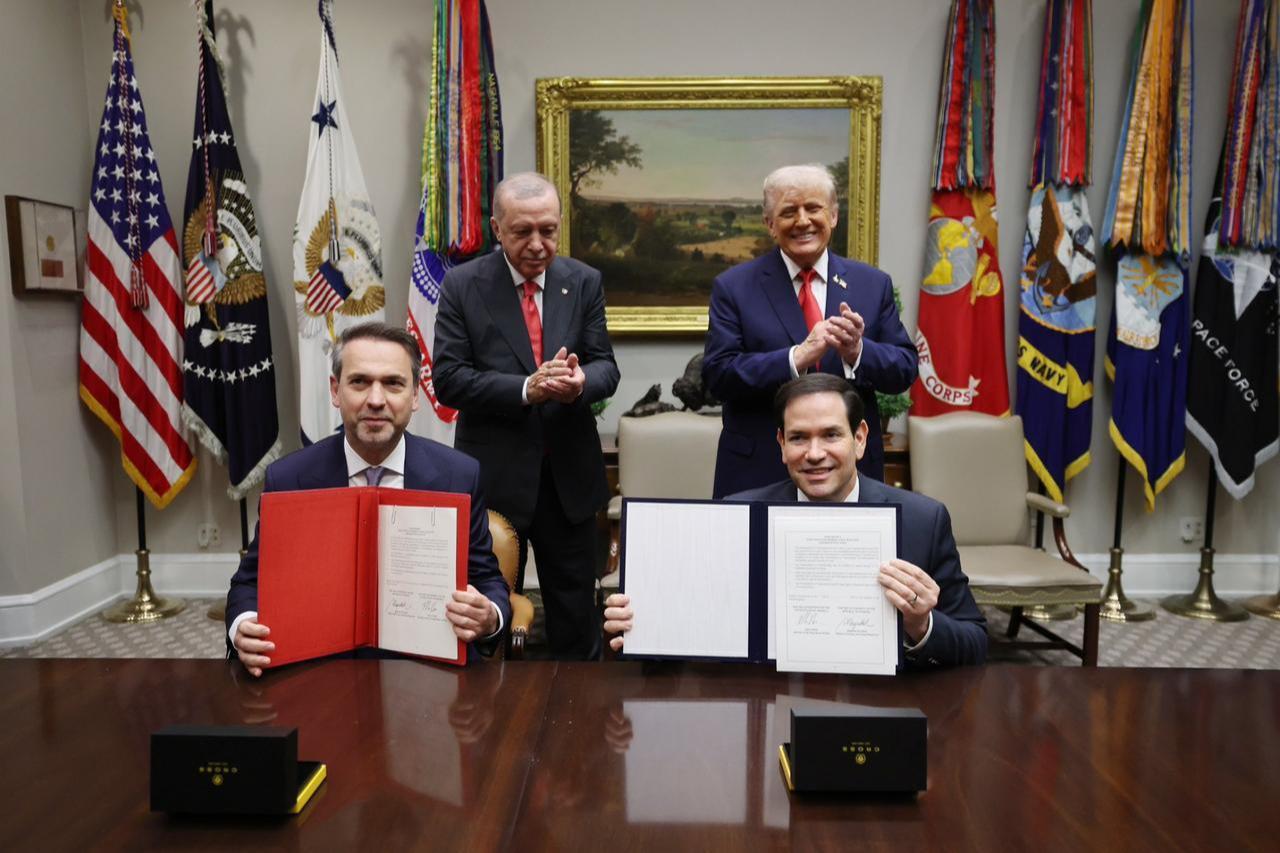

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan met U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House on Thursday, marking his first Washington visit in six years. The talks produced a series of high-profile announcements covering nuclear energy, defense cooperation, energy security, and regional diplomacy, signaling a potential reset in U.S.-Turkish relations after years of strain.

Among the headline outcomes were a civil nuclear cooperation agreement, discussions on LNG and diversification of energy supplies, and renewed dialogue on Türkiye’s possible return to the F-35 program. The two leaders also touched on the war in Ukraine, broader Middle East dynamics, and religious issues tied to the Orthodox Church, underscoring how the meeting went beyond bilateral disputes to shape Ankara’s wider international positioning.

Türkiye Today sat down with experts Pinar Dost, Sinan Ulgen, Feridun Tasdan, and Ali Alkis to break down the implications of the meeting.

Sinan Ulgen, director at EDAM, senior fellow at Carnegie Europe in Brussels, and a former Turkish diplomat, said, “It seems that the NATO issue as such has not really been discussed between the two leaders. The discussion centered much more on bilateral ties, some of which obviously have a NATO dimension.

Secondly, of course, the fact that Türkiye and the United States will, going forward, have a more robust relationship regarding the defense industry, provided that the CAATSA sanctions are lifted, the F-16 package remains in the pipeline and Türkiye is allowed to return to the F-35 program following a settlement over the S-400 issue, is in itself a positive development for NATO overall. Because these developments would not only increase Türkiye's air defense capabilities but ultimately, they would also serve to enhance NATO's deterrence. At a time when NATO's deterrence itself is being tested by these incursions in NATO airspace that we see more often from the Russian side.

Thirdly, the Ukraine issue should have featured as a major NATO topic. We don't haev much information about what was discussed between the leaders, but it can be said is that this trust-based relationship—to the extent we can define it as such with Trump—is also going to be helpful in mobilizing a NATO-backed effort for the security guarantees of the West.

Türkiye could play a major role on the issue of Ukraine's security guarantees. This is not going to be directly NATO business, but obviously it will involve many NATO countries. As things stand, the U.S. position has also evolved. The U.S. seemingly is willing to provide support for this security guarantees package that will be led by the European members of NATO. The exact nature of that support will probably take the form of intelligence sharing, air reconnaissance and air defense systems, and not really boots on the ground. That is something that European allies will need to take forward. As far as Türkiye is concerned, Türkiye's position is that Ankara is willing to contribute to this effort of putting together a package of security guarantees for Ukraine.

Türkiye sees its role to a large extent as being responsible for the naval aspect of that effort. And that obviously makes sense given that Türkiye does not want to create pressure on the Montreux Convention. So it wants to espouse this role with its own navy. Türkiye could also contribute to the air policing mission with its air force and possibly its fleet of drones. But as things stand, it is not clear whether Türkiye would also be ready to contribute to the land component of these security guarantees.

A key challenge for Ankara is that its current position appears to be that any package of security guarantees for Ukraine must have Russia’s assent. That is not, however, a position that is shared by other allies. They aim to frame this as leverage for Ukraine, potentially helping to draw Russia to the negotiating table. This difference will also need to be resolved if Türkiye’s role in future security guarantees for Ukraine is to be discussed.”

Pinar Dost is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Türkiye Program and a historian of international relations. She previously served as the program’s deputy director and is currently an associate researcher at the French Institute for Anatolian Studies. She said: “In fact, (former US President Joe) Biden and Trump’s foreign policies did not change fundamentally. Biden largely continued the policies of Trump’s first term. If we are to speak of a reset, it occurred through several breaking points in the relationship rather than through the presidents themselves.

The first was Russia’s attack on Ukraine in 2022. This war reminded America and the entire region of how important Türkiye’s geopolitical position really is. When it became clear that the European Union was unprepared for a war, the need for NATO’s second-largest army, a rising defense industry, and Türkiye’s combat experience across multiple fronts was recognized.

Trump’s idea at the beginning of quickly ending the war in Russia’s favor was the biggest difference with Biden. Such a result would have been extremely negative for Türkiye in terms of Black Sea and Mediterranean security. But Trump, both in his UNGA speech and his meeting with Erdogan, signaled that he will now follow a different policy. This is positive for Türkiye in the long run.

The downside, of course, is that in 2024 Türkiye still relied on Russia for about 41% of its natural gas supply. This requires new alternatives. The LNG sales and trade agreements signed with American companies both last year and yesterday are therefore very important steps. In the future, U.S. sanctions on Russia may also come onto the agenda, which would create significant challenges.

The second breaking point was the change in Syria’s regime dynamics. Türkiye’s role in this was once again recalled by Trump in today’s meeting. Since the end of the Qatar blockade, Türkiye has developed relations with all Gulf countries. This has encouraged the U.S. administration to resolve regional issues in partnership with Türkiye and Arab states.

The biggest challenge here is, of course, Israel, but Washington is making major efforts to ensure that this does not block progress in U.S.-Türkiye relations. Both a Damascus-SDF agreement and a Damascus-Israel agreement would be critical steps toward stability in Syria. The next step, I believe, will be the gradual normalization of Türkiye’s relations with Israel after the Gaza war and in a post-Netanyahu era—with the U.S. likely trying to play a mediating role.

Regarding today’s meeting, the most important issue was Trump’s statement that CAATSA sanctions could be lifted. Receiving the F-35s is important, but beyond that, the removal of restrictions on components needed for our domestic industry and their exports to third countries will be a huge relief for Türkiye. It will also weaken the hand of Congress, which is generally known for its anti-Türkiye stance.

In the coming period, I expect Turkish and American companies to work more closely in regions where Türkiye provides stability and security. Overall, it was a positive press conference. I think the Trump administration has understood that Türkiye is a crucial ally for burden-sharing both in the Black Sea and in the Middle East.”

Feridun Tasdan, professor at Western Illinois University, defense industry expert, said: “When evaluating diplomatic, regional, or military relations between Türkiye and the United States, the defense industry is among the most important issues. This has been the case especially from the 1970s to the present. The 1974 Peace Operation (in Cyprus) and the subsequent embargo, supply challenges for certain systems (most notably additional AH-1W helicopters) during the counterterrorism campaigns of the mid-1990s and the difficulties faced after 2020 each reflected period-specific conditions. Yet, at its core, the issue of arms embargoes remains a political lever in Washington today.

Today, the bilateral defense-industrial relationship is no longer limited to platform acquisition. Joint procurement projects carried out with Turkish firms (for example, the F-35 program) and the diversification of products sourced from the U.S. as subsystems (avionics, jet engines, aircraft parts) have changed the nature of the relationship. Looking in detail at the topics that surfaced in the Erdogan–Trump meeting, in my view, the removal of the CAATSA sanctions imposed on Türkiye in 2020 is the single most important obstacle to defense industry cooperation between the two countries. The ban on the Presidency of Defense Industries (SSB), imposed after delivery of the S-400s from Russia and the CAATSA sanctions that followed, prevents or delays the procurement of major or sub-system supplies for important nationally funded defence projects financed by the SSB, and slows the issuance of necessary export licences from the State Department. One of the main items on the agenda at today’s meeting could therefore be lifting these CAATSA sanctions. Under the law, President Trump could lift sanctions tied to the S-400 and other military/security relations with Russia if Türkiye provides sufficient assurances; this issue will be on the bilateral agenda. The S-400 problem will need a joint solution negotiated between the two countries’ military delegations.

Similarly, F-35 deliveries are linked to CAATSA. The U.S. green light for F-35s and the possible acceptance of six F-35s already produced but not delivered in the United States depend on this sanctions framework. The 2020 U.S. defense budget law (NDAA) contains a provision halting F-35 deliveries to Türkiye; if the CAATSA conditions described above are met, a letter of assurance from President Trump to Congress and perhaps a broader consensus could reopen the F-35 path. The removal of both the F-35 restriction and the sanctions on the SSB is tied to the S-400 issue: the NDAA states that the prohibition continues while Türkiye has the S-400. Thus, the two countries will have to find a solution for the S-400.

Other major agenda items could include engine supplies for Türkiye’s key aviation projects, KAAN and Hurjet—specifically F-110 and F-404 engines—because Türkiye has invested heavily in these programs and views KAAN as the backbone of its future air defense. For this reason, agreement between the parties is required to procure the critical F-110 engines for initial KAAN production. Discussions could also cover the possibility of establishing local production at TEI in Eskisehir. I foresee a minimum procurement of 100–120 F-110 engines. If the 40-plus spare engines for the F-16 Block-70 procurement are included in the same package, the total number of F-110 engines required could rise to the 160s, which would make opening a TEI production line more economical.

The Patriot procurement project mentioned by President Trump today is, in my view, not surprising. In recent years, we have seen extensive use of ballistic missiles in the region—both in Ukraine and in the Gulf, including strikes against Qatar, Saudi Arabia or Israel. While Türkiye continues to prioritise domestic systems such as SIPER and HISAR and to design projects cumulatively (for example, under the "Iron Dome" concept), we still lack ballistic-missile interception capability. To acquire that capability quickly, Türkiye might consider procuring Patriot air-defence systems that use PAC-3MSE interceptors. The long-range SIPER system currently in our inventory protects primarily airborne threats—aircraft, helicopters, drones or cruise missiles—but has not yet gained ballistic-missile-defeat capability. Roketsan and SAGE are working on this, but if the need is urgent, Türkiye could consider procuring perhaps four Patriot batteries equipped with PAC-3MSE interceptors.

The long-delayed F-16 Block-70 procurement—whose final obstacles I do not understand why it took so long—should proceed once remaining issues are resolved, because this acquisition project has already dragged on for nearly two to three years. The package envisaged the purchase of 40 new F-16 Block-70s along with necessary Legion pods, the ALQ-257 EH system, new-generation AMRAAM missiles and launchers.

Of course, there may also be other defense industry procurements or co-production topics discussed that have not been made public. Most of these would concern small-scale spare parts or component supplies, or areas where the two sides could undertake joint military cooperation.”

Ali Alkis, junior associate fellow at NATO Defense College, said: “Looking at the energy agreements from the meeting, the Memorandum of Understanding on Strategic Civilian Cooperation stands out as particularly significant. Türkiye signed a cooperation agreement back in 2008 on the peaceful use of nuclear energy, so renewing it was important, as it turns U.S.–Türkiye ties into a strategic partnership.

Small modular reactor and nuclear technology transfers strengthen Türkiye’s energy security, while reducing dependence on Russian resources. For example, there is a $43 billion LNG import framework over 20 years, with potential U.S. investments aiming to add a capacity of 35 billion kilowatt-hours annually. This alone can cover 10% of Türkiye’s energy deficit.

The small modular reactors and nuclear technology transfers strengthen Türkiye’s energy security, while reducing dependence on Russian resources. For example, there is a $43 billion LNG import framework over 20 years, with potential U.S. investments aiming to add 35 billion kilowatt-hours annually as capacity. This alone can cover 10% of Türkiye’s energy deficit.

Regionally, reopening the Iraq–Türkiye oil pipeline could also promote stability.

In NATO terms, these agreements strengthen Türkiye’s strategic position. Support for Ukraine, ammunition production, and closing the Straits to weaken Russia’s fleet are clear advantages.

Trump has also argued for allies to spend 5% of their budgets on defense. These nuclear deals balance Russian alternatives and make collective security and trans-Atlantic ties more sustainable. Despite some criticisms, the integrated renewable model minimizes environmental risks and symbolizes NATO’s move toward energy independence.”