Over the recent years, a series of violent incidents involving minors has pushed juvenile justice back into the national spotlight in Türkiye. The January 2025 stabbing of 14-year-old Mattia Ahmet Minguzzi by two teenagers, followed by threats against his family and vandalism of his grave, generated widespread outrage. Prosecutors escalated the investigation by treating it under organized crime statutes, but the move failed to calm public anger.

Only months later, in May 2025, the death of 9-year-old Yusuf Taskin in Konya, after a classroom altercation with a peer, added to a sense of urgency. The fact that Taskin’s older brother had died years earlier after a similar school dispute deepened public unease.

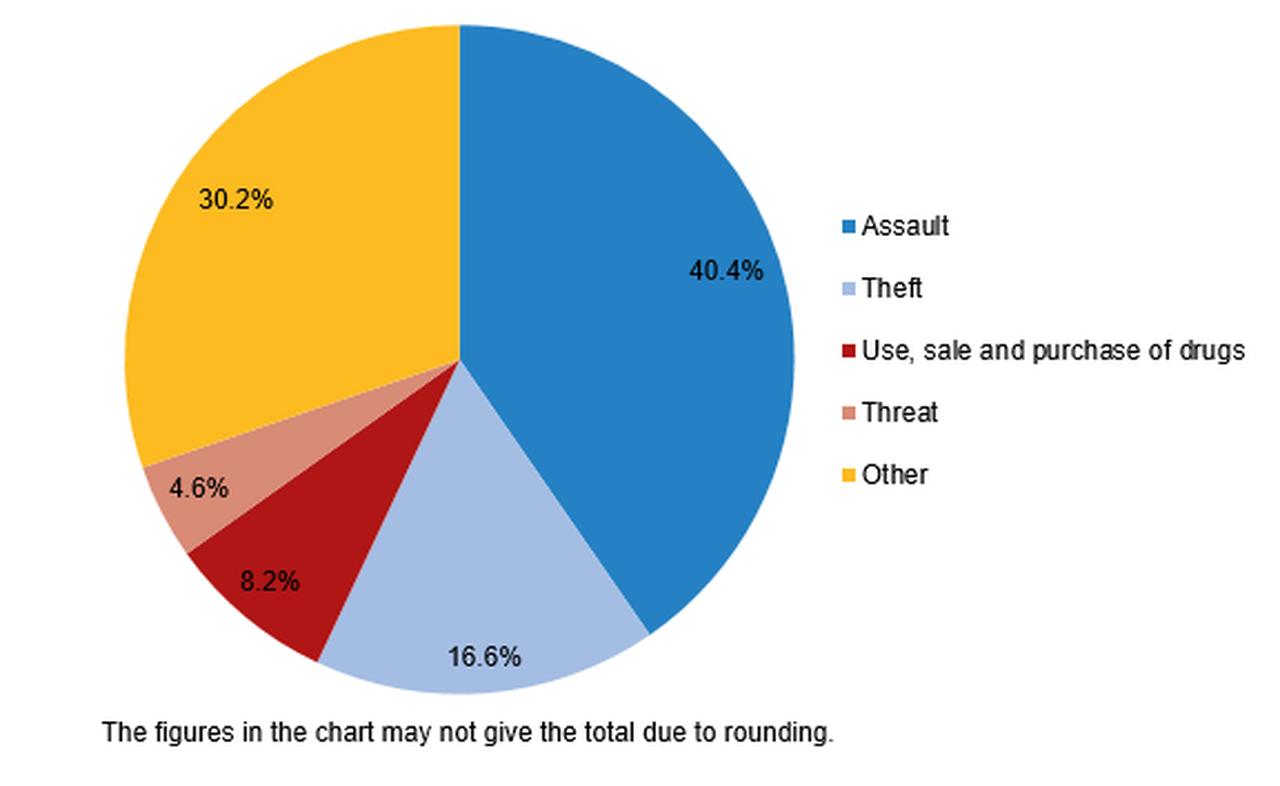

Now reports of high school brawls and even primary-level violence have since reinforced perceptions that youth crime is neither rare nor isolated. Last year, security units recorded over 200,000 incidents involving juveniles accused of committing a crime.

Following widespread public outrage over the large number of children with criminal records before reaching the age of 18 and the abuse of children by adults, Justice Minister Yilmaz Tunc made statements at the opening ceremony of the 2025-2026 judicial year.

Announcing that a draft bill was being prepared regarding changes to the law concerning children involved in crime, Tunc said, “We are working on reducing sentencing discounts as the age increases.”

Turkish law, in line with international standards, treats everyone under 18 as a child. Criminal responsibility begins at age 12, though liability varies by age group: those between 12 and 15 are deemed partially responsible, while 15- to 18-year-olds face sentences closer to those of adults but with reductions.

The current framework emerged with the Child Protection Law of 2005, which introduced the term “child dragged into crime.” The legislation was designed to prioritize rehabilitation, requiring specialized courts and mandating the presence of psychologists or social workers during questioning. Detention is intended as a last resort, with judges instead encouraged to impose educational or social measures.

The principle that delinquent minors should be treated as victims of broader social failings has long shaped Turkish juvenile justice. Advocates argue that many offending children have themselves suffered from abuse, neglect, or exploitation, and that the system should address those vulnerabilities first.

Yet critics question whether this victim-centered approach has gone too far. In the Minguzzi case, one perpetrator posted about the attack online and had previously shared images posing with weapons. For opponents of the current model, such behavior undermines the idea that offenders are merely passive victims of circumstance. They argue that some minors act with intent and awareness, and that the law should reflect this distinction.

Research has shown that many minors accused of crimes demonstrate a level of understanding about the consequences of their actions. A medical review of cases from 2018 found that more than half of children aged 12 to 15 grasped the legal meaning of their acts, while nearly a third had prior records. Security officials also report high rates of reoffending among children brought in at a young age.

This has raised concerns that lenient sentencing may inadvertently expose minors to further criminal networks, setting them on a path of repeated offenses. Without stronger preventive and protective systems in schools and communities, critics warn, lighter penalties risk failing both the offender and society.

Some legal professionals insist that all delinquent children remain victims to some degree. The Istanbul Bar Association’s Children’s Rights Center, for instance, has stressed that protecting minors is a collective responsibility. But others contend that this stance overlooks the rights of children harmed by their peers and erodes public trust in the justice system.

Proposals are emerging to refine terminology and approach. Concepts such as “high-risk youth” are being discussed as alternatives or complements to the existing “child dragged into crime” framework. Such shifts could allow policymakers to distinguish between vulnerable minors in need of support and those who commit severe crimes with full awareness.

Another important issue is that shocking events upset the balance between extremes. According to some claims currently circulating on social media, it is possible that crimes committed by minors could also affect their parents, thereby undermining the principle of individual responsibility for crime. This would be a regulation of such magnitude that it could cause changes in family dynamics in many ways and lead to social transformation.

No further wounds should be inflicted on the social wound created by crime, and while compliance with universal and international norms remains essential, Türkiye needs to develop its own solution.

The debate is no longer only about how to punish or protect juvenile offenders. It is also about how to ensure that children, whether victims or perpetrators, are not failed twice by a system struggling to keep pace with the realities of modern youth crime.