Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahceli, one of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s most significant allies, has called for Türkiye to forge a strategic alliance with Russia and China. His remarks, delivered against the backdrop of Israel’s Gaza offensive and changing U.S. policy toward Ankara, immediately raised questions about feasibility.

For Bahceli, the reference point was historical: he likened the present moment to 1964, when U.S. President Lyndon Johnson sent a stern letter to Prime Minister Ismet Inonu during the Cyprus crisis, warning against unilateral military action. Inonu's retort—“A new world will be established, and Türkiye will take its place in it”—resonated in Bahceli’s framing. But the conditions of today’s world, and Türkiye’s geopolitical entanglements, make his proposal far from straightforward.

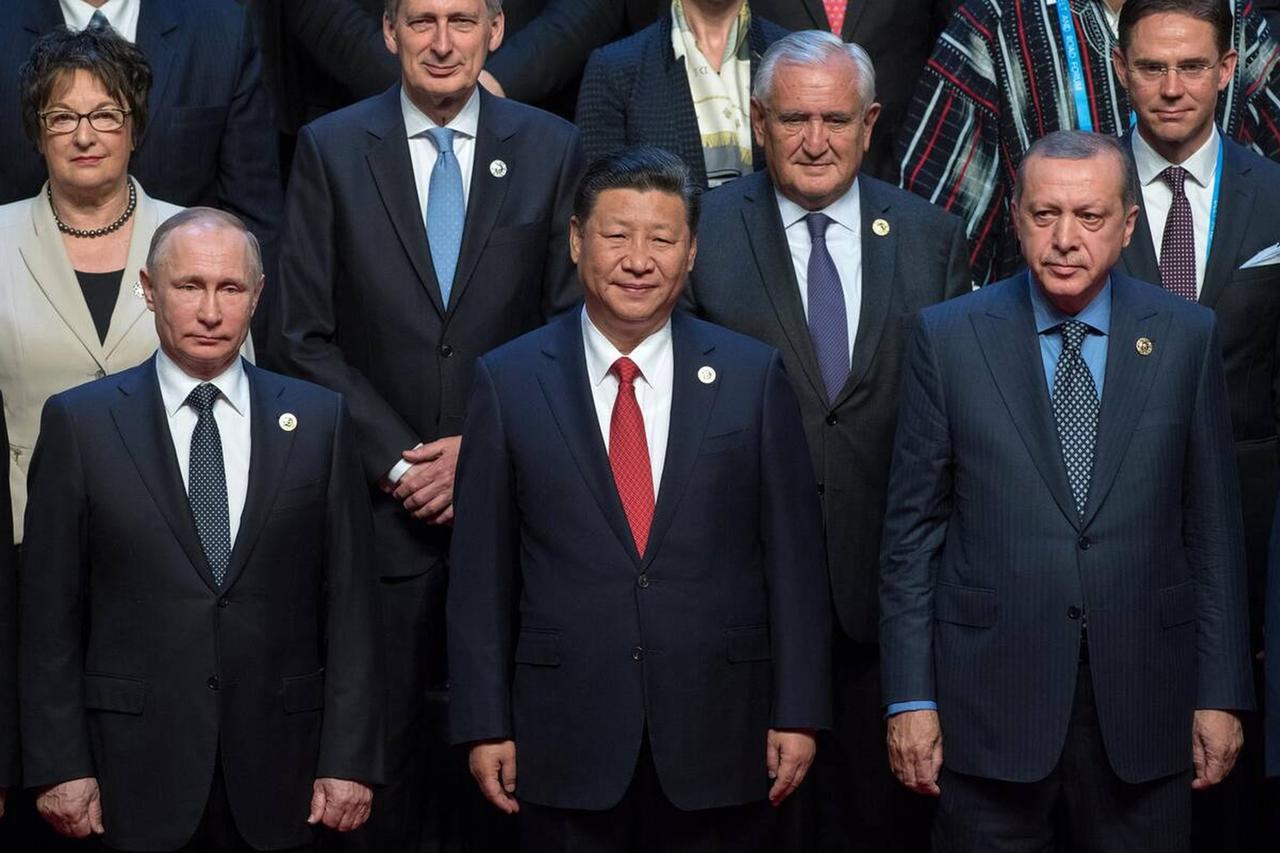

“The issue Bahceli raised is actually in line with policies the Turkish state has already been pursuing,” the director of Heydar Aliyev Center for Eurasian Studies, Yasar Sari, pointed to President Erdogan’s recent attendance at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in China—where Türkiye was the only NATO member present.

“Could Türkiye completely abandon NATO, its alliance framework, or its economic ties with Europe? In the short term, no. But it is also a warning to the United States and European countries, because Türkiye now has the capacity to pursue its own path.”

But even talking about a shift in alliances remains premature for the country, which has both a long road ahead and plenty of reasons to hold back.

In international relations, “alliance” implies more than close cooperation. It signifies a binding, formalized commitment between states—something both Russia and China have historically avoided. Analysts caution that to speak of an alliance, rather than strategic alignment or pragmatic cooperation, risks overestimating what is politically and diplomatically achievable.

China’s foreign policy doctrine emphasizes initiatives like the Global Security and Global Civilization initiatives, which promote multipolar engagement but explicitly steer clear of bloc politics.Beijing frames its global posture as post-alliance, preferring flexible partnerships to rigid commitments.

Russia, while more accustomed to bilateral security arrangements, benefits strategically from Türkiye’s ambiguous position inside NATO. Ankara’s balancing role—at once a NATO member and a partner to Moscow—creates space for Russian maneuvering within the Western alliance. Transforming this delicate balance into a formal Türkiye-Russia pact would run counter to Moscow’s interest in preserving cracks within NATO.

Türkiye and Russia already maintain robust ties across multiple domains: energy, nuclear power, trade, tourism, and defense. Projects such as the Akkuyu nuclear power plant, heavy Russian tourist inflows, and close energy interdependence highlight the depth of existing relations.

Yet this cooperation coexists with stark contradictions. In Syria, Ankara and Moscow have repeatedly found themselves on opposite sides of the conflict for over a decade. In Libya, they backed rival factions. Even in the South Caucasus, their influences counter each other. The relationship has been characterized less by alignment than by compartmentalized, transactional pragmatism.

For Türkiye, defense procurement is a decisive indicator of alignment. The 2019 purchase of Russian S-400 missiles marked a watershed moment, triggering U.S. sanctions and exclusion from the F-35 fighter jet program. Yet subsequent steps suggest Ankara is not abandoning its Western defense orbit.

Most recently, Türkiye revived its push for Eurofighter Typhoons, part of a broader strategy to sustain air force modernization within NATO frameworks. Defense cooperation with Russia remains limited and politically sensitive, while China’s role in Türkiye’s defense posture is marginal. In this light, a formal alliance with Moscow and Beijing appears strategically incongruous with Türkiye’s ongoing reliance on Western military ecosystems.

Another obstacle lies in Türkiye’s domestic trajectory. Since its republican founding in 1923, the state-society model has rested, however unevenly, on democratic legitimacy and individual freedoms. Governments have varied in their fidelity to these principles, but no administration has fully disavowed them.

Aligning formally with Russia and China—two states defined by authoritarian governance—would run against the grain of Türkiye’s centurylong orientation. Such a bloc could be perceived not only as a geopolitical but also as an ideological pivot away from democracy, raising questions about domestic legitimacy and the republic’s founding consensus, according to Hasan Unal, a professor and expert on Turkish foreign policy.

The economic dimension also complicates Bahceli’s call. According to Sinan Ulgen, director of the Istanbul-based think tank EDAM and senior fellow at Carnegie Europe, Türkiye’s most balanced and prosperity-generating trade relations remain with the European Union, where annual trade volume surpasses $210 billion. With China, by contrast, trade is highly asymmetrical: Türkiye imports around $45 billion worth of goods from China while exporting only about $5 billion.

Though the proponents of alignment with Beijing often cite BRICS as an alternative framework, and noting its share of global gross domestic product (GDP) and reserves, the organization lacks cohesive political glue, operating largely as a platform for dissatisfaction with Western-led institutions rather than a functioning economic or security bloc. The internal rivalries between members—such as India and China—underscore its limits, per the analyst.

Underlying Bahceli’s call is the broader shift toward multipolarity. Many Turkish policymakers agree that the post-Cold War unipolar order has eroded irreversibly. In this context, Türkiye’s pursuit of diversified relations with non-Western powers is widely seen as both logical and necessary.

Türkiye’s Cold War history provides precedent: even at the height of U.S.-Soviet rivalry, Ankara maintained significant trade with the Soviet Union, securing heavy industry projects that strengthened its domestic economy. Today, similar opportunities exist with both Russia and China, particularly in energy, infrastructure, and technology.

But framing such engagement as an “alliance” rather than pragmatic, bilateral cooperation risks overpromising and underdelivering. Multipolarity creates space for maneuver, but it does not erase the constraints of existing alliances and economic realities.

Bahceli’s timing was deliberate: his call came as Israel intensified its military operations in Gaza, with broad Western backing. For him, Russia and China represented potential counterweights to what he labeled an “evil coalition” of the United States and Israel.

Yet both Moscow and Beijing have taken cautious positions on Israel’s actions. Neither has offered the kind of decisive opposition that might satisfy Turkish critics of Israel. Russia maintains its own channels of cooperation with Israel, especially in Syria, while China has avoided entanglement in Middle Eastern conflicts beyond rhetorical gestures.

This raises questions about whether Russia and China are the reliable partners Bahceli imagines when it comes to restraining Israel’s regional conduct.

Bahceli’s proposal is unlikely to reshape Turkish foreign policy in the immediate term. Yet it carries domestic political weight. By invoking historical memory and voicing dissatisfaction with Western conduct, he positions himself—and by extension the government coalition—within a broader debate about Türkiye’s strategic orientation.

Although such a change does not seem possible in the short term, and President Erdogan does not have policies in this direction, such rhetoric can be understood as the need to break free of Western dependency and encourage more strategic autonomy. For critics, however, it reveals the tension between nationalist political messaging and the structural realities of Türkiye’s global position.