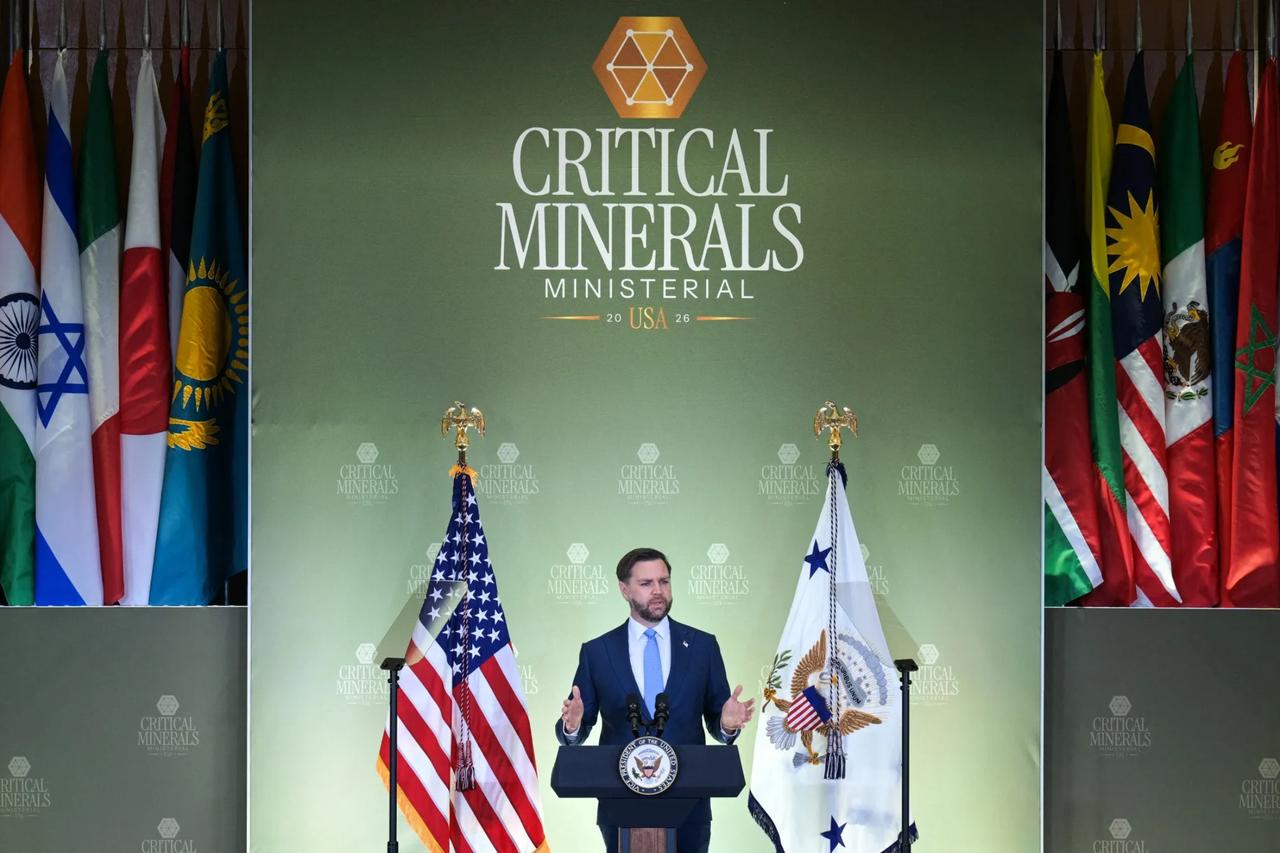

On Feb. 4, 2026, Washington hosted the Critical Minerals Ministerial, bringing together representatives from 54 countries and the European Commission. With 43 ministers in attendance, the meeting aimed to coordinate a new global supply chain for minerals essential to modern economies, including those used in electric vehicles, smartphones, defense systems and power grids.

The political objective was clear. China currently dominates both the mining and processing of many critical minerals, in some cases controlling more than 90% of global supply. U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio framed this concentration as a risk not only to markets but also to global security and stability.

Beijing’s leverage is not limited to domestic production. Through the Belt and Road Initiative, China has secured long-term access to mineral resources across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and has shown willingness to weaponize supply chains when political disputes arise.

Against this backdrop, the question of Türkiye's absence becomes even more glaring, especially when compared to the presence of producers with far less regional output.

Türkiye was not represented at the ministerial, despite being geographically close to Europe and economically intertwined with Western markets. The day following the summit, a panel on US Critical Minerals Policies and Türkiye's Geoeconomic Position was held in Istanbul, hosted by the Istanbul Mining Exporters' Association (IMIB) in collaboration with TABA–AmCham.

According to Sait Uysal, founder of the Critical Minerals Initiative Türkiye, this absence does not reflect a lack of interest from abroad, but rather a lack of effective engagement at home.

“There is constant outreach from different countries and official institutions asking about rare earths and cooperation opportunities,” Uysal said. “I am sure similar requests reach Türkiye as well, but most likely they cannot find the right counterpart.”

Speaking to Türkiye Today, Uysal argues that Türkiye has not articulated a coherent critical minerals strategy that aligns mining, processing, industry, and end markets. Without this ecosystem in place, participation in such alliances risks remaining symbolic rather than transformative.

Critical minerals, particularly rare earth elements, only generate value when they are processed and integrated into industrial supply chains. Uysal stresses that raw production without downstream capacity leaves countries dependent on China as the sole buyer.

“If you produce rare earths and do not process them, the only buyer today is China,” he said. “Once you process them into magnets, motors, or components, you need a domestic or allied market large enough to absorb that output.”

This challenge extends beyond manufacturing. Processing rare earths requires a strong chemical industry, advanced engineering, and strict environmental regulation. Radioactive waste management, especially due to thorium and uranium by-products, demands institutional capacity that Türkiye has yet to fully develop.

Rather than focusing narrowly on rare earth elements, Uysal believes Türkiye’s comparative advantage lies elsewhere. Lithium, he argues, offers a clearer path to building a full value chain linked to the existing industry.

“Türkiye could be one of the world’s largest lithium producers,” Uysal said, pointing to lithium content embedded in boron mining waste. While boron itself is often described domestically as strategic, its real untapped value may lie in the lithium extracted from associated residues.

Türkiye already has battery production capacity, which creates the possibility of converting domestically produced lithium into batteries and, ultimately, electric vehicles. “Once you turn lithium into batteries, you lock in value,” Uysal noted, describing how this could multiply economic returns across the supply chain.

Türkiye’s potential extends well beyond lithium. Uysal highlights titanium-bearing iron ores that could reduce dependence on imported scrap and pig iron, a major vulnerability in Türkiye’s steel sector. These deposits often also contain vanadium, a high-value metal used in energy storage and advanced alloys.

There is also evidence of gallium and germanium presence in historic mining waste, particularly in central Anatolia. “We identified significant gallium in old slag piles,” Uysal said, adding that Türkiye lacks a comprehensive inventory of such resources despite their relevance to defense and semiconductor industries.

Compared with Europe, where opening a new mine can take nearly two decades, Türkiye’s regulatory timelines are shorter, and its infrastructure, including energy, transport, ports, and skilled labor, is already in place. This positions the country as a natural candidate for near-shoring and friend-shoring strategies.

Uysal sees no structural reason for Türkiye to stay outside emerging critical minerals alliances. The obstacle, he argues, is internal rather than external. “There is no reason not to join,” he said. “What stops it is our own mindset.”

He points to bureaucratic inertia, fragmented authority, and a tendency to overstate existing capabilities. In one example, he points out, a proposal to produce tens of thousands of tons of lithium carbonate from solid waste stalled for years, despite political support at senior levels.

“We often convince ourselves that we already know everything and can do everything,” Uysal said. “That leads to the conclusion that we do not need partnerships, technology transfer, or new strategies.”

With its resource base, industrial capacity, and geographic proximity to Europe, Türkiye remains well-positioned to become a key node in non-Chinese supply chains. Doing so, however, requires acknowledging institutional gaps and adopting a clear, credible strategy.

As Uysal puts it, “Türkiye has no shortage of potential. What it needs is the willingness to break its own internal barriers and turn that potential into policy.”

Türkiye’s absence does not preclude future participation, but delay carries costs as supply chains harden and partnerships deepen in other parts of the world.