American author Ursula K. Le Guin once said:

“Story is something moving,

something happening,

something or somebody changing."

During Italy’s visa crisis, I found myself living two lives at once: that of a student trapped in bureaucratic limbo, and that of a journalist compelled to document the ordeal. This essay is both a personal account and an attempt to capture the wider picture of a system that failed thousands.

My reason for becoming a journalist has never changed: to pursue the truth. And as Le Guin reminds us, the more stories told, the more truths revealed. I chose to hold onto one of these stories because today, a student who dreams of studying in Europe can end up fighting for that right in a courtroom rather than a classroom. I, along with nearly a thousand others, was forced into that reality.

This is not merely a diplomatic quarrel or a question of numbers; it is a process that reached deep into individual lives. The stories of those affected, including my own, are proof enough.

In June 2024, I received my admission letter from Rome Business School’s Master’s program in International Media and Entertainment Management. It was meant to be the moment where my 10 years of professional experience in media would merge with international academic training, elevating my career to the next stage.

The curriculum, the opportunities, and the chance to engage directly with Rome’s global media ecosystem were thrilling.

As a multilingual journalist, I was equally eager to learn Italian, often described as one of the world’s most beautiful languages.

I submitted my documents to the Italian Consulate in Istanbul at the end of August, full of anticipation, never suspecting how dramatically the journey would twist. Like every student, I wanted only to begin my master’s degree and advance my career.

The problems, however, began almost immediately. Booking an appointment through IDATA, the intermediary agency, meant months of waiting. By the time the consulate finally replied at the end of October, three more months had already passed.

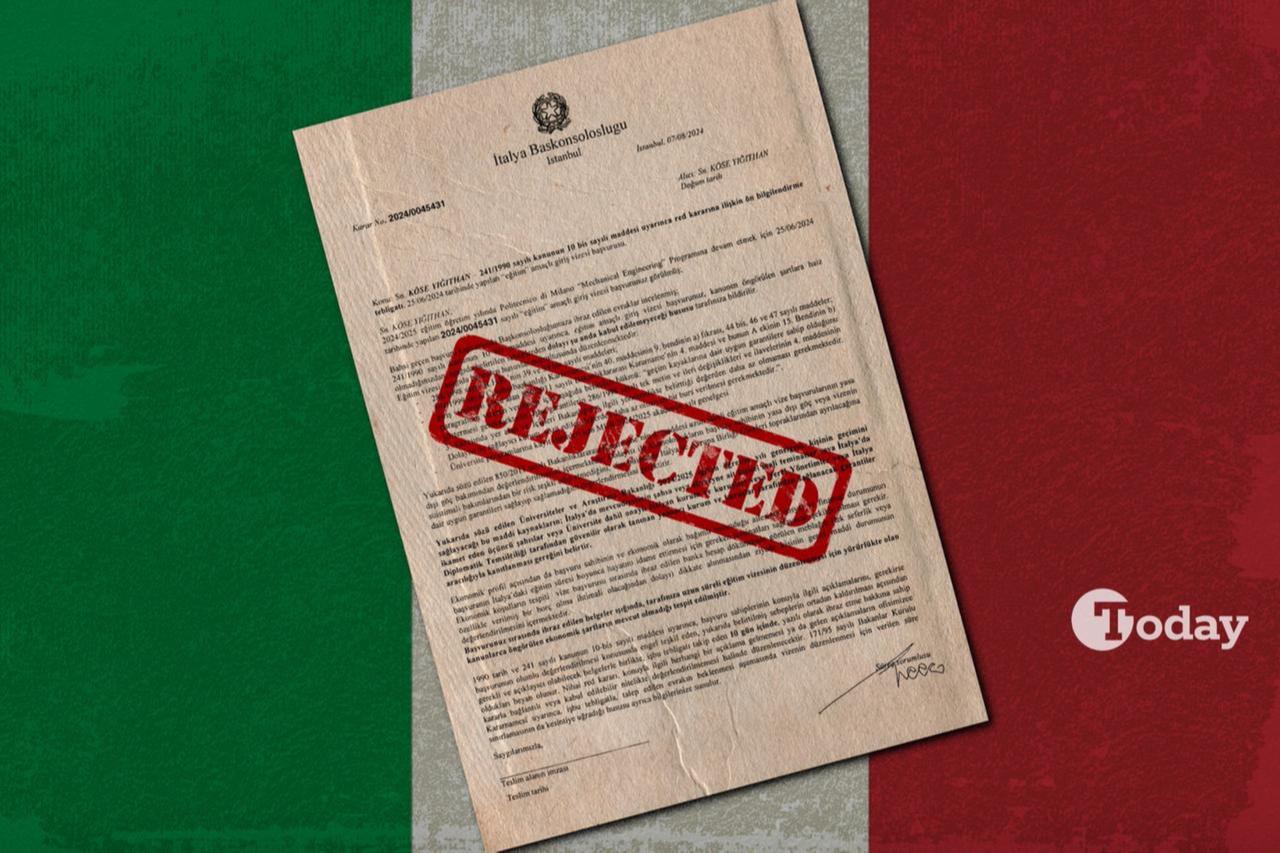

The verdict was devastating: refusal.

The reason cited was “risk of asylum.”

Every document had been completed, every requirement fulfilled—yet I was suddenly treated not as a student, but as a potential refugee.

Once the initial shock wore off, I had no choice but to try again—this time applying through the Italian Embassy in Ankara. Yet even after months of waiting, the outcome was the same: in January 2025, I received another refusal.

By then, my program had already started, and I was struggling to follow classes online while still trapped in a maze of unanswered emails, unreturned calls, and endlessly rescheduled flights and housing reservations.

At first, I assumed this was my own unlucky misfortune. However, conversations with other Turkish students at the Rome Business School, and the research I undertook, revealed something much larger: hundreds of us, graduate, undergraduate and Erasmus students, were living the same story.

Many had waited months without a response, unable to reach anyone at the Istanbul or Izmir consulates, sometimes not even receiving a formal rejection.

By October, months of unanswered calls and emails left students with no choice but to make their situation heard. Together with their families, they gathered outside the Italian Consulate in Istanbul, delivered a press statement, and left a black wreath as a symbolic gesture. Nov. 29 marked the final deadline to enroll in their universities, and for many, that chance was slipping away.

The first stories in the Turkish media captured the urgency of the moment. Wanting to shield my peers from further harm, I used my experience as a journalist to help make their situation visible.

A single tweet I posted was shared thousands of times, reaching millions. Students organized through WhatsApp groups and launched social media accounts under the name Unsa Italy to share their experiences and the injustices they faced.

The response was immediate: my phone rang constantly, with worried students, desperate parents, and lawyers seeking background information, as well as reporters chasing interviews. What began as scattered frustration was becoming a collective voice.

Amid these efforts, the Go-For Youth Organizations Forum requested a meeting and held talks with the Italian Embassy in Ankara. Embassy officials acknowledged delays caused by high application numbers and admitted that their own guidelines had not always been clear, particularly on financial requirements and document formats, promising to make future revisions.

Yet, in framing refusals largely as the result of incomplete files, their response shifted responsibility onto students without addressing the structural issues. The reality, as we soon witnessed, was that these statements did little to ease the crisis; if anything, the uncertainty only deepened.

Recognizing that diplomacy alone would not resolve the crisis, Go-Far prepared a policy brief and shared it with Marco Grimaldi, a member of Italy’s Chamber of Deputies, bringing the issue directly before Parliament.

The Italian–Turkish Friendship Association voiced support, while students at Ca Foscari University in Venice displayed a banner reading “Turkish Students Are Welcome.”

Yet alongside solidarity came exploitation. Major visa consultancy firms publicly accused rejected students of being careless, insisting they had failed to prepare their files properly. Others seized the crisis as a marketing opportunity, advertising “100% guaranteed visa applications.” On social media, some mocked the students: “Why insist on going to a country that rejected you? Maybe you deserved it.” For students already exhausted, these attacks deepened the sense of being trapped and humiliated.

As the issue stayed on the agenda, it grew into more than a problem for a handful of students: it exposed the broader structure of the Schengen visa system itself. Turkish media, from national broadcasters to independent outlets, gave it headline space.

TRT World, NTV, CNN Turk, Haberturk, TRT Haber, Halk TV, Türkiye Gazetesi, Anadolu Agency, Euronews, VOA Turkish, Daily Sabah—across the spectrum, the story could no longer be ignored. I appeared on television programs, including one with journalist Nevsin Mengu, while others, such as Cuneyt Ozdemir, debated the matter live on air.

Since the problems first came to public attention, the numbers tell their own story. According to Brand24, reports appeared on 186 different websites; 516 media outlets covered the issue; 20 YouTube videos were published; and 126 posts appeared on LinkedIn.

Social media engagement reached 138 million, with 137,000 recorded interactions. More than 2,300 mentions were tracked across platforms, including X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, online news sites, and YouTube—while negative sentiment rose by an astonishing 841%.

This surge was not the work of a single campaign, but rather the convergence of many voices—mainstream outlets, independent journalists, student networks, and civil society. It was fueled not only by public support but by the undeniable truth of the students’ plight. Every day, new live programs gave them a platform. Every day, new sectors of society expressed support.

The pressure in Türkiye soon echoed in Italy. On Nov. 19, 2024, Anadolu Agency’s Rome correspondent reported a statement from Italian Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani: “There is absolutely no obstacle for Turkish students to come and study in Italy.” The words sounded reassuring. Yet on the ground, nothing changed. Rejections continued, appointments were scarce, and anxiety deepened.

The gap between official statements and lived reality was widening. Investigative reporting by Türkiye Today revealed rejection letters riddled with errors, including misspelled students’ names and incorrect listings of universities or departments.

Starting Nov.24, the picture grew even grimmer; between 30 and 50 new refusals were issued each day.

By Nov.29, most students had been unable to enroll, effectively losing their academic year. Some would have to apply to universities all over again, despite the months of preparation and financial sacrifice already invested.

For those unwilling to accept this injustice, only one path remained: the courts. In January and February 2025, students announced they would sue the Consulate General of Italy in Istanbul. Their argument was simple but unshakable: a right once granted, the right to education had been unlawfully denied.

After months of uncertainty, a turning point came in March when Rome’s Lazio Regional Administrative Court issued a precedent-setting decision. For some students, the court ordered that visas be granted directly; for others, it required the consulates to review their applications within five days, stating that the same vague justifications could not be used again.

Most importantly, the court underlined that suspicion alone could never serve as grounds for refusal; only clear and substantive evidence could. Around twenty students won their cases, and in doing so, they set a legal precedent with implications far beyond their own files.

This was not just a personal victory for a handful of young people. It was the first time that the recurring injustices of the Schengen visa system had been formally acknowledged and corrected by law. For Turkish citizens, students, academics and businesspeople alike, it opened a door that had long seemed closed. What these students achieved carried historic weight: they transformed an individual struggle into a broader legal safeguard.

In effect, students who had been denied entry to lecture halls in Rome were instead writing history in its courtrooms. They compelled the system to confront its own failures and carved out a future not only for themselves but for those who would come after.

What began as a fight for the chance to study became a lesson in the enduring strength of law: that rights once denied can be reclaimed, and that even the most rigid bureaucracies can be reshaped through precedent.

According to a March 31, 2025, report by Euronews, Italian Deputy Foreign Minister Maria Tripodi announced that student visa applications from Türkiye had risen by 36.6 percent compared with the previous year.

She added that consulates in Ankara, Istanbul, and Izmir had increased their capacity and were making “extraordinary efforts” to process applications as quickly as possible.

Yet, from conversations with students directly affected, I know that such statements, polished in the language of diplomatic courtesy, did little to ease the uncertainty on the ground, nor could they restore the academic year that had already been lost.

At the same time, notable developments were unfolding on the international stage. During President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s visit to Italy on April 29, it was announced that discussions had taken place on facilitating visas for both students and businesspeople.

On July 15, 2025, the European Union announced the adoption of a new set of more favorable Schengen visa rules for Turkish citizens, known as the “cascade rule,” aimed at facilitating people-to-people contact.

The announcement, coming in the shadow of recent hardships, raised the question: would this finally translate into tangible improvement?

Around the same time, reports were circulating of intense back-channel traffic between Ankara and Rome. These accounts, never officially confirmed but widely discussed in diplomatic circles, suggested that relevant institutions were quietly engaging in talks, that channels long dormant were beginning to stir.

Whether these moves were directly linked to the students’ legal struggle is uncertain, but the coincidence of timing was difficult to ignore.

What happened next came as a surprise to many. The Italian Consul in Istanbul, Irene Pastorino, completed her term in Türkiye, news first shared by Consul General Elena Clemente on her X account.

Shortly after, the Italian Embassy’s official channels confirmed the appointment of her successor, Roberta Cotanzo.

Many of the rejection letters, including my own, bore Irene Pastorino Olmi’s signature. To describe her departure as merely a coincidence seems inadequate. As Socrates once observed, “In the universe, there is no such thing as chance.”

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the progress achieved so far was made possible through the convergence of media attention, public diplomacy, social networks, student solidarity, and the dedication of countless volunteers. The power of news coverage and public pressure seemed to resonate even behind closed doors.

The outcome we secured was more than a visa victory; it offered hope to many young people in Türkiye and, though it came late, a measure of consolation to those who had been wronged. Yet from conversations with fellow students, I know the struggle is far from over.

Some cases remain in court, while others, despite favorable rulings, are still waiting for their visas at the Istanbul consulate.

This hard-won progress must be preserved. We owe it to the determination, strength, and dreams of young Turkish people to believe in them and to support them. The presence of law, media and human rights advocacy is among the greatest assets any society can possess.

Through all of this, I also managed to complete my year of study. On Sept. 11, I will defend my master’s thesis online. Perhaps I could not present it at a faculty podium in Rome, but as a Turkish student, I witnessed how Roman law, with its precedents and historic rulings, defended the rights of students far more powerfully than I ever could.

As Lao Tzu reminds us: “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

We took that step.