The six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—share a common geography but diverge sharply in their visions, capacities and ambitions.

Despite their proximity, these countries occupy distinctly different positions on the spectrum of economic power, technological maturity, and military modernization.

This asymmetry makes the Arab Gulf one of the most competitive policy arenas in the world, where cooperation often yields to rivalry.

Beyond regional politics, each state’s foreign partnerships—with the United States, China, Russia, and Europe—shape its technological and defense policies.

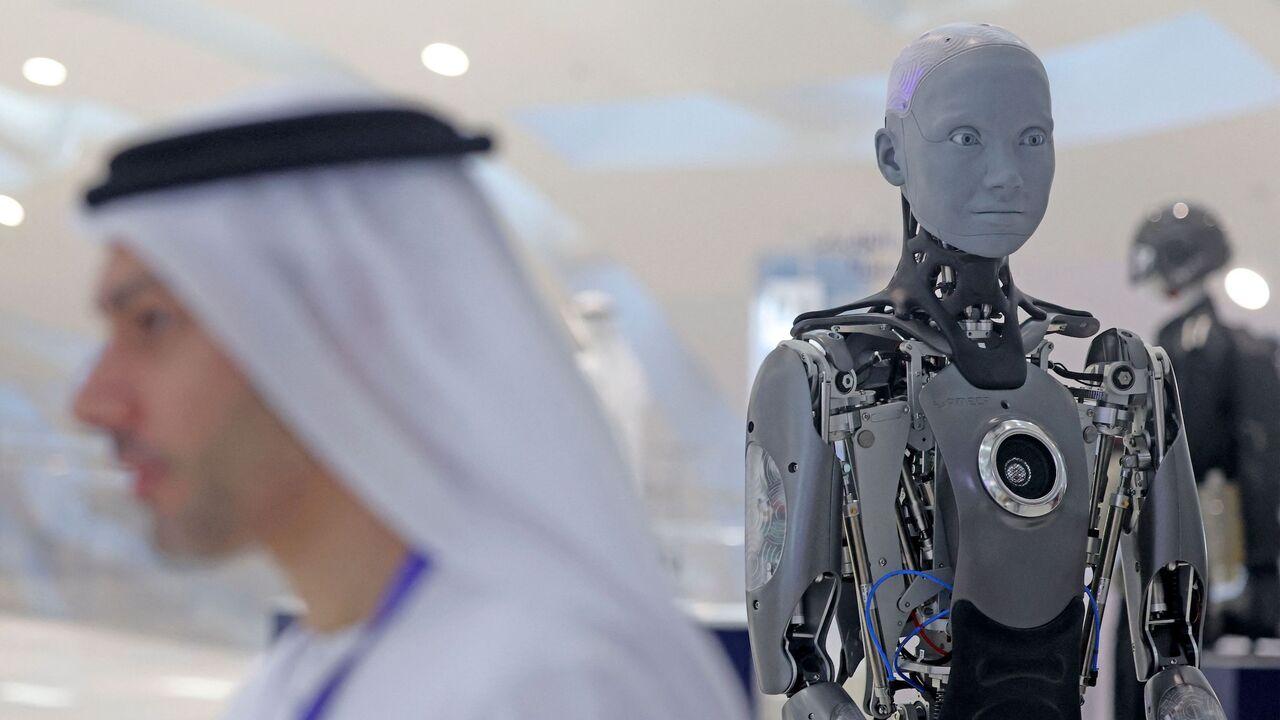

Nowhere is this divergence clearer than in the field of artificial intelligence.

A new country study by Heiko Borchert for the Defense AI Observatory (DAIO) at Helmut Schmidt University underlines how defense artificial intelligence (AI) has become a key marker of power in the region—one that blends technological ambition with geopolitical calculation.

The study underscores that AI has emerged as a “trophy technology,” deployed to legitimize rulers, diversify economies and modernize armed forces.

Yet the uneven distribution of wealth and expertise ensures that not all GCC members move at the same pace.

Among Gulf states, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar lead the race to embed AI into defense structures.

These three nations have launched extensive national AI strategies and begun integrating advanced applications into air defense, command-and-control systems, predictive maintenance, and cybersecurity.

Their initiatives are ambitious but also competitive—each seeking to position itself as the region’s technological hub.

In contrast, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Oman are still in the early stages of adoption. While all six GCC members have formally acknowledged AI’s importance, their strategies remain vague when it comes to its role in national security.

For most, defense AI is viewed primarily as a way to enhance the agility and responsiveness of their armed forces to regional threats rather than as a transformative military doctrine.

Developing local defense AI capacity is closely tied to broader efforts to strengthen domestic defense industries. Across the GCC, governments are investing heavily in digital ecosystems, establishing partnerships abroad to facilitate technology transfer and skill development.

This outlines how Arab Gulf states use strategic investments abroad to build industrial strategic depth to advance the use of AI.

Yet the report cautions that practical implementation remains limited. Current use cases often center on predictive analytics, space-based observation, and automated maintenance systems.

The transition toward full operational integration faces cultural and institutional barriers—notably centralized decision-making and compartmentalized information flows within the armed forces.

Borchert highlights that these structural constraints must be addressed if Gulf militaries are to fully exploit AI’s potential. Building organizational agility and encouraging a culture of initiative are as critical as acquiring advanced technology.

The DAIO report illustrates that Arab Gulf governments are not only importing AI technologies but also advancing their own regulatory frameworks. These frameworks aim to balance alignment with Western partners—especially the United States—with the development of AI language and data models grounded in Islamic values.

According to Borchert, such efforts serve two purposes: first, to ensure that AI applications reflect local ethical norms; and second, to make Gulf digital economies more attractive to international investors by signaling regulatory maturity. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, in particular, are using AI regulation as a soft-power tool, positioning themselves as normative leaders in shaping global AI governance.

This dual approach—modernization coupled with cultural authenticity—allows Gulf states to maintain what the report calls “geostrategic equidistancing.” It enables them to engage with Washington, Brussels, Beijing, and Moscow simultaneously, without fully committing to any single technological bloc.

However, the lack of policy synchronization across the region complicates collective progress. Efforts to harmonize defense AI frameworks remain fragmented, with each nation pursuing distinct partnerships and infrastructure priorities. For now, alignment appears more aspirational than achievable, according to the report.

Digital transformation has also entered the bureaucratic sphere. The UAE, for instance, has appointed chief AI officers across federal agencies, while Oman has created a dedicated directorate for AI and advanced technology.

Kuwait and Qatar are following suit, signaling an evolving institutional mindset. Yet, the integration of AI into defense institutions remains uncertain, constrained by traditional hierarchies and centralized decision-making.

Local strategic cultures—marked by compartmentalized information flow and limited encouragement of independent initiative—pose challenges to effective AI integration.

Overcoming these habits will require structural reforms that foster innovation and adaptability within military institutions.

The report also underlines the massive scale of Gulf digital infrastructure spending. According to Borchert, “three-digit billion” investments are being directed toward data centers, AI-compatible cloud systems, and language models tailored to regional contexts.

However, he stresses that hardware and software investments alone cannot ensure success.

Human capital development remains the most decisive factor. Gulf nations are expanding education programs and reforming military training to include AI literacy. Initiatives such as appointing Chief AI Officers in the UAE or establishing dedicated AI units in Oman are early signs of institutional adaptation.

Yet, as Borchert observes, partnerships with foreign universities aim to cultivate domestic expertise in AI-related fields, while military academies are updating curricula to include AI applications.

Joint exercises with foreign militaries, particularly under US-led frameworks such as the Navy’s Task Force 59, expose Gulf forces to advanced defense AI concepts. However, the impact of these initiatives is not yet measurable.

Such funding underscores the seriousness of the Gulf states’ intent—but also highlights their dependency on imported expertise. Building truly sovereign AI capabilities will require more than hardware; it demands sustained knowledge transfer and policy coherence.

Another major insight from the DAIO study is how Arab Gulf states use strategic investments abroad to expand their industrial and technological depth. By investing in international digital and defense ventures, they secure access to cutting-edge knowledge, facilitate technology transfer, and enhance their local ecosystems.

The report emphasizes that these cross-border partnerships are not merely commercial. They represent a deliberate strategy to position Gulf states as co-developers—not just consumers—of emerging defense technologies.

For example, Abu Dhabi’s and Riyadh’s sovereign wealth funds play an increasingly active role in financing startups and research centers specializing in defense AI, robotics and cybersecurity.

Such outward investment, the study notes, adds “strategic depth” to local industries while reducing dependency on traditional Western suppliers.

It also enables Gulf countries to link their defense AI ambitions with broader goals of economic diversification and national branding.

Yet this ambition exposes a paradox: while these nations emphasize regional leadership, their defense AI ecosystems remain shaped by external partnerships and imported technology.

Data sovereignty, model governance, and regulatory autonomy are emerging as critical pressure points that could redefine how AI integrates into Gulf defense structures.

All in all, mastering AI technology is only part of the equation; cultural, organizational, and educational reform will determine whether the region can truly transform its military and defense industries. For now, the record seems to remain mixed.