“Ah, home.”

“People usually believe home is where the heart is, but what if you have your heart in two places? Can we have two homes in this world?” Nine-year-old Ehtisham* asked pensively. He was born and raised in Türkiye’s Kayseri but had always imagined Syria’s Damascus—the place his parents had always spoken of with quiet reverence—as his abode. Ehtisham completed his elementary schooling before joining a football academy in Türkiye, but now it’s time...time to return home.

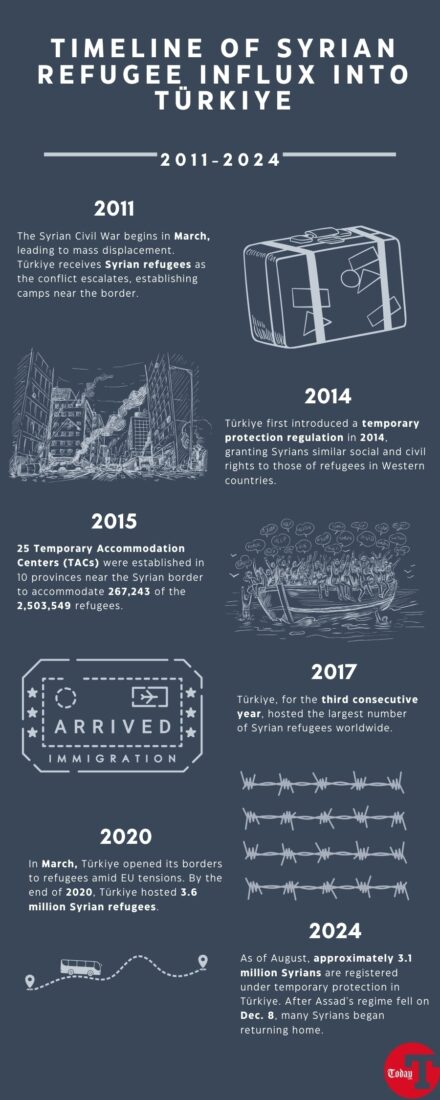

Ehtisham, who aspires to become a prolific footballer like famed young Turkish football star Arda Guler, is one of the 3.2 million Syrian refugees Türkiye hosts, being one of the largest refugee host countries worldwide. Following the former Syrian regime leader Bashar al-Assad’s fall in Damascus on Dec. 8, the collapse of the 61-year Baath regime was celebrated with immense joy in Türkiye’s Istanbul. Jubilation, fear of the unknown, and hope permeated through the nooks and crannies of Fatih streets, among many other districts of the metropolis. “What’s next?” was the looming question on many minds.

Between 2012 and 2015, a significant influx of Syrian refugees into Türkiye took place when millions fled the Syrian Civil War, saving themselves from intensified conflict, human rights violations, and economic afflictions.

“There were a zillion reasons for which we had left Syria, and with Assad’s fall, all those reasons are now gone,” maintained Yousef Saleh, a Syrian sociologist and social activist based in Istanbul. He had escaped the tyranny of the Assad government, arriving in Türkiye from Aleppo in 2013 when he was just 22. But now, being a father of two, he seems certain about his future for his family in Syria.

“I am extremely happy. This is the first time in my life that I belong somewhere. This feeling of belonging is amazing,” Saleh shared, reflecting on the post-Assad era.

Sharing about his preparations for his voluntary return to Syria, including legal documentation, Saleh explained that the Turkish government has launched a portal to facilitate safe returns. “With this new portal, it seems like things will proceed smoothly, but some Syrians are reluctant to apply, as doing so means giving up their temporary protection ID and leaving Türkiye permanently. Nobody is forcing anyone right now, but uncertainty still looms large.

Saleh added that the decision could become easier if Türkiye or other countries allowed temporary visits, which are currently unavailable. “I feel the Syrian refugees at this point seek security and assurance before wrapping up their lives once again and making such a high-stakes decision. This reluctance likely roots from the torment they’ve endured, compounded by years of displacement and fear,” he said with a sigh.

Returnees are permitted to enter Syria via officially assigned border gates in Türkiye after they have finalized the necessary documentation, with women and children given priority during the process. Up to December 2024, Ankara has opened a number of crossings in order to enable the voluntary and safe return of Syrian refugees back to their country.

These border crossings include the Cilvegozu Border Crossing in Antakya, which is connected to the Syrian gate of Bab al-Hawa, from where hundreds of refugees have been queuing up to come back. The Oncupinar Border Crossing in Kilis, which is connected to the Syrian gate of Bab al-Salameh, has seen huge numbers of refugees coming in. The Yayladagi Border Gate in Hatay province has now been opened for the safe return of the refugees as well. In the backdrop of the current political climate in Syria, these initiatives come in line with the nation's broader efforts to enable the safe return of refugees.

Several Syrian refugees heading to their home, in Kilis, Türkiye, June 8, 2018 (AA Photo)

Reportedly, 90% of Syria’s population remains below the poverty line. Putting forward his concerns and the uncertainty regarding the future, Saleh said, “I am fully aware of the rocky road ahead, but I still want to return home. Living in Türkiye is a constant reminder to me that I am a Syrian and I have to return home.

He also pointed out the rising anti-Syrian sentiments in some parts of the country, the unspoken cultural divide, and the economic woes. Having said that, Saleh recalled his landlord, who was a 78-year-old Turkish man. He affectionately calls him "baba" (father in Turkish). Saleh mentioned how kind he was and how he will always cherish his unwavering support over the years. “Acceptance is a process," he said.

"All these experiences don't concern how good or bad a person is. It’s all about how considerate and kind you are,” Saleh observed, highlighting both the troubles and the tiny acts of kindness that he experienced during his journey in Türkiye.

With so much unpredictability and instability surrounding the transition of Syrian refugees from Türkiye to Syria, another crucial issue often flies under the radar. According to a 2021 UNICEF report, there were approximately 1.7 million Syrian refugee children in Türkiye. Given the current circumstances, a significant portion of the Syrian refugee population in Türkiye is likely under 18.

“The majority of Syrian refugees in Türkiye are teenagers or people in their early 20s. Having been born in Türkiye, attended Turkish schools, and formed deep connections with Turkish friends, many of these young Syrians don’t even speak Arabic. This transition will undoubtedly be pivotal and challenging for them,” Saleh noted. He explained that, despite his efforts to speak Arabic with his nine-year-old son at home, his son primarily uses Turkish, as he attends a Turkish public school.

“I might not even continue my education when I go back to Syria because I don’t know Arabic,” admitted 12-year-old Noor, who never stepped outside Istanbul.

Pundits raise concerns that language barriers, cultural differences, and contrasting social norms could trigger an identity crisis among young Syrians returning to Syria, especially those who were born and raised in Türkiye. Having grown up in a different cultural environment, many may struggle to adapt to Syria's post-conflict realities and to build a sense of belonging to both countries. The dominance of Turkish culture in their upbringing and their limited fluency in Arabic may hinder their access to education, employment, and social integration when moved to Türkiye

“We might be perceived as ‘outsiders’ in Syria despite our roots and heritage, while in Türkiye, we face discrimination as refugees. So, I ask myself sometimes, Who are we?” questioned Ehtisham, expressing concerns that dual exclusion could amplify feelings of alienation.

Despite these challenges, Saleh remains positive about the future. When asked about his expectations for his life in Syria, he chuckled lightly. “Well, that’s a question you should ask me when I’m in Syria. To be honest, the future doesn’t worry me much—it’s something we’ll build together,” he said, exuding hope for better days ahead.

*Names have been changed to maintain anonymity.