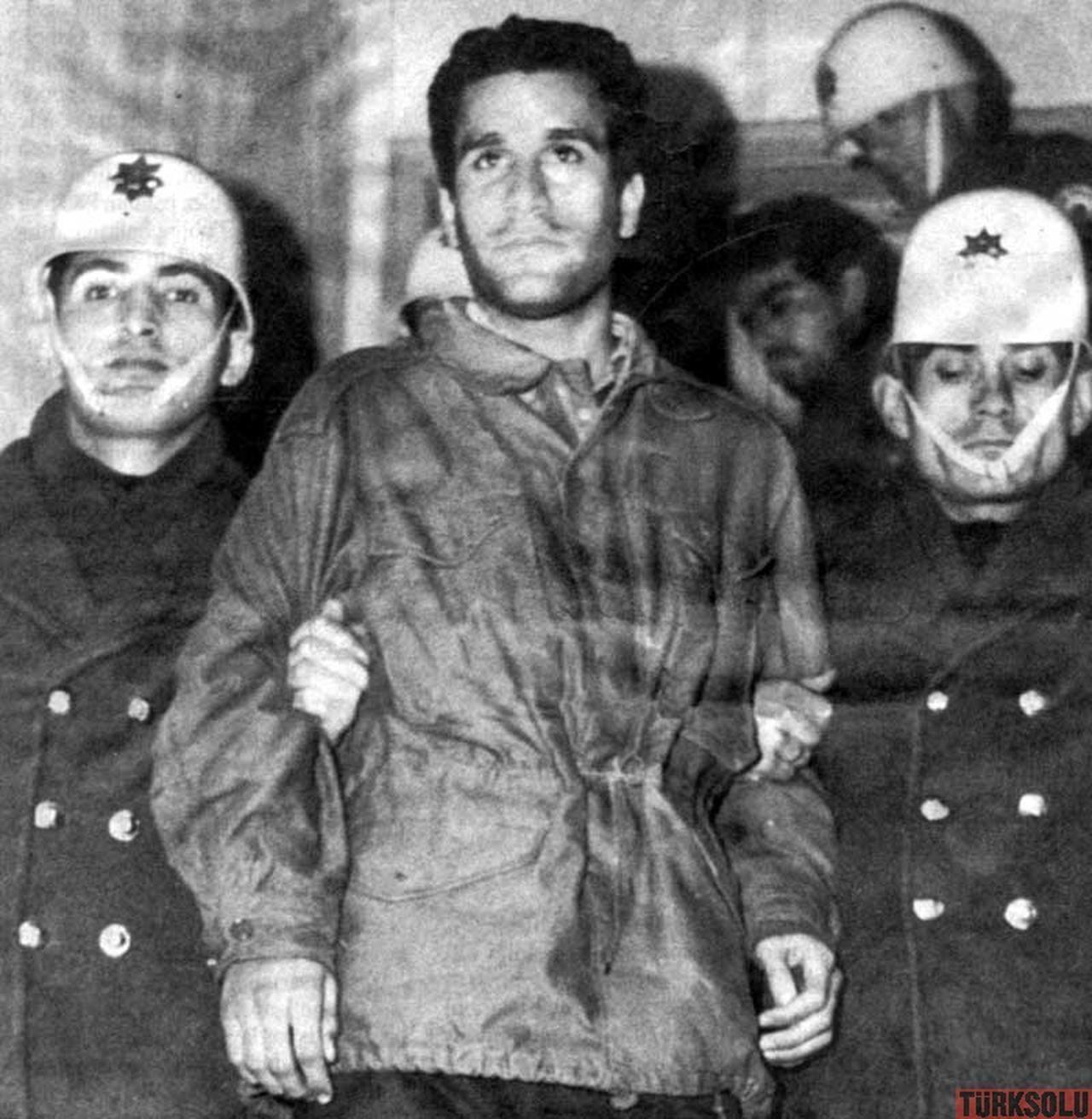

Autumn 1969. A rumor swept through the universities of Türkiye, whispered from one restless student group to another—a whisper that would soon awaken a generation. The winds in the Middle East were still harsh in the autumn of 1969. The Arab world was struggling to recover from the trauma of the 1967 defeat, entering a new era of political reorientation. That November, a rumor swept through Türkiye’s universities—one that would soon define a generation. Students whispered that leftist student leader Deniz Gezmis and his comrades had gone to Palestinian camps for guerrilla training. The trip itself was brief, almost symbolic, yet its resonance endured for decades across Turkish society.

At the time, Palestine was one of the rare causes that united fiercely divided ideologies. For the Turkish left, it embodied anti-imperialism and the universal fight for liberation. For Islamists, it symbolized the consciousness of the ummah and a sacred duty of solidarity. For nationalists, it evoked the memory of Ottoman lands and a sense of historic responsibility.

These perspectives rarely overlapped—but when they did, they created a remarkable moral consensus. Through newspapers, journals, and poetry, the country’s fractured intellectual landscape produced a single, shared heartbeat for Palestine.

The 1970s marked one of Türkiye’s most turbulent decades. The March 12, 1971, military memorandum, university protests, and violent clashes between leftist and nationalist groups turned campuses and city streets into battlegrounds. Within this turmoil, revolutionary factions inspired by internationalism viewed the Palestinian camps as both training grounds and moral laboratories of resistance.

The Turkish state, meanwhile, responded to growing unrest with martial law and strict internal security policies. Student unions and labor organizations framed their solidarity with Palestine not merely as political activism but as a moral stance against global injustice.

In 1968, for instance, the Middle East Technical University (METU) Student Union sent a telegram to Jordan’s King Hussein condemning Israel and expressing solidarity with Arab nations—an act that highlighted both the intensity of student sentiment and the delicate line the government had to walk between diplomacy and domestic pressure.

At the same time, journalists and academics amplified Palestine’s story, shaping the public’s moral imagination. Young volunteers who set out from Türkiye carried food, medicine, and supplies—often departing from the Syrian Consulate in Istanbul’s Tesvikiye district. This was not simply a revolutionary gesture but an act of civic conscience, a movement that cut across ideological divides.

For the radical left, the Palestinian struggle represented both a revolutionary ideal and a practical space to learn warfare. For conservatives and nationalists, it was a matter of strategic caution and historic duty. Despite this divergence, the emotional resonance of Palestine persisted.

By the summer of 1979, one slogan echoed across Turkish cities: “Jerusalem belongs to Islam.” The Iranian Revolution had upended the regional order; Egypt’s peace with Israel left it isolated; and Palestine once again became a symbol of identity and defiance.

The rallies in Istanbul, Konya, Ankara, and Diyarbakır were not just political gatherings—they were moral demonstrations. For a fleeting moment, distinctions between right and left, religious and secular, nationalist and socialist blurred. Palestine became the mirror in which the Turkish conscience saw itself.

This was a rare moment of unity in Türkiye’s modern history. Unlike other foreign policy causes, Palestine stood for something deeper—the very idea of justice. Writers, filmmakers, and diplomats all joined in this moral chorus. Collaborative works between leftist and Islamist intellectuals revealed how the Palestinian question could transcend ideological borders and become a shared moral horizon.

When the First Intifada erupted in 1987 and Yasser Arafat proclaimed an independent Palestinian state the following year, Türkiye quickly became one of the first Muslim-majority countries to recognize it. Even under military rule and political restriction, public solidarity did not fade.

The rise of the PLO and Hamas diversified Türkiye’s domestic engagement with Palestine. Leftists focused on human rights and international law; Islamists on the ummah and religious solidarity; nationalists on historical and cultural bonds.

Throughout the 1990s, as Türkiye and Egypt supported the Oslo peace process, the Turkish public remained deeply sympathetic to the Palestinian cause. Polls conducted between 1995 and 2000 indicated that roughly 70% of Turks supported Palestine, though opinions differed on the means: diplomacy and aid versus resistance and symbolism.

Academics, journalists, and diplomats explored the issue through legal, humanitarian, and geopolitical frameworks, keeping Palestine at the center of Türkiye’s shared moral consciousness.

Hamas’s rise to power in Gaza in 2006 reshaped regional dynamics. While Egypt, Israel, and the United States aligned in caution, Qatar and Türkiye pursued engagement. During the Gaza wars of 2008, 2012, and 2014, Doha emerged as a lead mediator, while Ankara positioned itself as a humanitarian and moral force—sending aid convoys and leading international calls for accountability.

The 2010 Mavi Marmara incident, in which Israeli forces attacked a Turkish humanitarian flotilla, reignited Türkiye’s domestic empathy for Palestine. Public outrage reached its peak, transforming solidarity into a national moral reflex. Yet by then, the Palestinian issue had evolved from a moral cause into a multi-layered diplomatic file.

As the Arab Spring unfolded, new rifts appeared. Egypt’s 2013 coup closed its channels with Hamas, allowing Qatar to take the lead in reconstruction efforts after the 2014 Gaza war. Türkiye focused on humanitarian assistance and international law, carving out a distinctive role that combined moral authority with pragmatic diplomacy.

By the mid-2010s, no single actor could dictate the trajectory of the Palestinian question. It had become a regional equilibrium—an arena where each state projected its own security and diplomatic agenda.

The Hamas-led assault of October 7, 2023, reignited not only a conflict but also Türkiye’s collective conscience. Once again, massive rallies filled the streets of Istanbul and Ankara, echoing the energy of the 1979 Jerusalem demonstrations. Civil society groups, religious communities, and individuals from across ideological lines came together in a unified call for justice.

The Palestinian issue reemerged as a moral touchstone, transcending politics. Intellectuals and journalists made the case visible both domestically and internationally, aligning public emotion with state diplomacy.

By October 2025, the cease-fire in Gaza marked a milestone—not only for regional peace but also for Türkiye’s evolving role. In the negotiations held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Türkiye acted as both mediator and trusted interlocutor, leveraging years of dialogue and credibility with Hamas.

President Erdogan’s active involvement—channeled through National Intelligence Organization (MIT) chief İbrahim Kalın—made Ankara’s goals clear: to end the war, ensure humanitarian access, and help establish a framework for long-term stability.

Türkiye’s coordination of humanitarian operations through AFAD and civil society organizations underscored its dual identity: a nation driven by both conscience and strategic purpose.

Today, Türkiye’s presence at the diplomatic table represents more than geopolitical ambition—it embodies the convergence of national conscience and statecraft. Yet, difficult questions remain:

Can this moral-diplomatic balance evolve into a sustainable model for regional peace? Can stability and humanitarian aid in Gaza truly be secured? And most crucially, can the delicate balance between public conscience and realpolitik endure?

The answers will not only determine Türkiye’s regional future, but also define how morality and power can coexist in the modern Middle East.