When Ankara announced its “Asia Anew Initiative” in August 2019, the policy was seen as a bold effort to rebalance Türkiye’s foreign relations eastward. The strategy aimed to strengthen political, economic, and cultural ties with Asian nations through a more comprehensive and institutional approach. It also sought to expand Türkiye’s engagement with key regional organizations such as the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

Türkiye’s integration into these multilateral structures has gradually redefined its standing as a “balancing power” within Asia—a role that has not gone unnoticed in New Delhi. India increasingly sees Türkiye’s rising visibility in Asian diplomacy and its growing defense and trade presence across the Indian Ocean region as an encroachment on what it considers its strategic sphere of influence.

Türkiye’s renewed interest in Asia goes beyond its traditional alignment with Pakistan. Ankara has strengthened ties with Bangladesh, once a reliable partner of India, and developed growing relationships with six Indian Ocean island nations: Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Mauritius, Madagascar, and the Seychelles.

The development most emblematic of New Delhi’s concerns came during the 2024 India–Maldives crisis, when Türkiye supplied drones to the Maldivian government for exclusive economic zone monitoring.

On the other hand, India’s self-image as the “big brother” of the Indian Ocean island nations has not always been well received. Local resistance has grown in Seychelles, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives, where Indian military presence and fisheries disputes have sparked domestic backlash. The 2023 election of Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu, who ran on the slogan “India Out,” underscored the limits of India’s regional appeal.

While geopolitical rivalry shapes one layer of the Türkiye–India relationship, ideological divergence adds another. The Hindutva ideology guiding India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) views the world through a lens of cultural nationalism that elevates Hindu identity above the country’s pluralistic heritage. Within this framework, both Muslims and Turks have become central to India’s construction of the “Other.”

This phenomenon, where national identity is reinforced through contrast and exclusion, has deep historical roots. In postcolonial India, Muslims and Turks replaced the British as the “historical adversary”, embodying a perceived threat to Hindu civilization. Türkiye’s vocal support for Pakistan and its stance on Kashmir have only reinforced this perception.

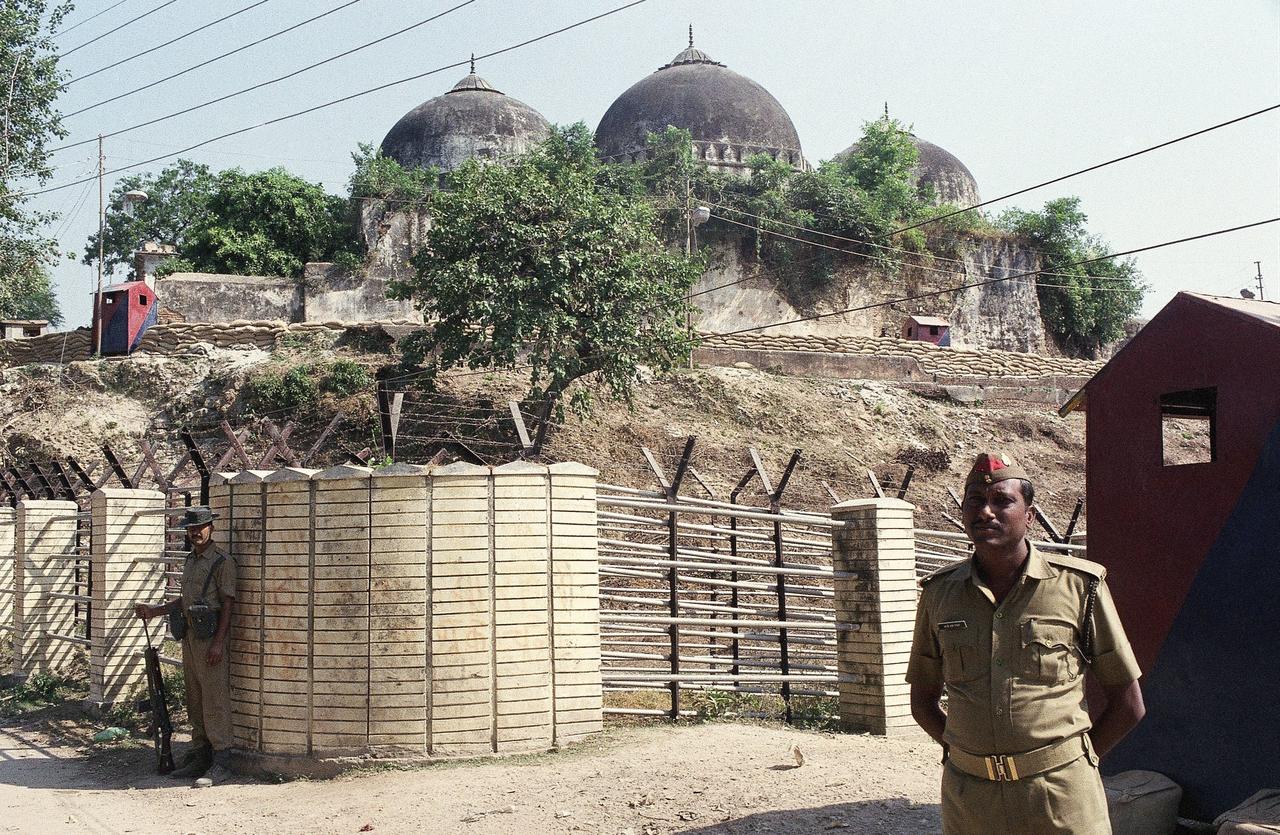

From a Hindutva perspective, Turks are not just Pakistan’s allies but descendants of the Mughal Empire, which ruled India from 1526 to 1858—a period that Hindu nationalists often reinterpret as a time of subjugation. Consequently, modern Türkiye is sometimes viewed not as a distant Eurasian power but as a symbolic reminder of Muslim dominance in Indian history.

This narrative has fueled broader efforts to erase Islamic cultural markers from public life. The renaming of cities and landmarks—from Allahabad to Prayagraj, Faizabad to Ayodhya, and Aurangabad to Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar—reflects a deliberate attempt to craft a Hindu-centric historical memory. Even the Taj Mahal, India’s most iconic monument, has occasionally been targeted by hardline groups calling for its demolition.

In this context, new Indian foreign policy appears eager to be involved in anti-Turkish alliances and besides already providing military support to Armenia, it currently attempts to expand cooperation with Southern Cyprus based on an adversarial mindset.

For New Delhi, the historical grievance of the Southern part of the Cypriot Island offers a diplomatic opening. Recent developments highlight how the two countries are aligning their agendas. Cypriot ports have been opened to Indian naval visits, and joint communiqués have emphasized maritime sovereignty.

The alignment reflects a subtle but clear anti-Turkish undertone in New Delhi’s Mediterranean diplomacy.

These moves, coupled with Cyprus’s EU membership, provide India with both symbolic and strategic leverage in the eastern Mediterranean.

This collaboration aligns with New Delhi’s connectivity ambitions through the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a maritime and railway network that links India to Europe via the Arabian Peninsula and the Eastern Mediterranean. Notably, Türkiye is excluded from IMEC, signaling the underlying geopolitical competition embedded in these economic frameworks.

Despite its momentum, the India–Cyprus partnership remains pragmatic and transactional rather than institutionalized. The asymmetric partnerships often involve a trade-off between protection and access. While the stronger state provides political weight, the smaller partner offers geographic or strategic advantages.

In this case, India gains a presence in the Mediterranean while Cyprus leverages India’s economic scale to enhance its geopolitical value within the EU. Yet the partnership lacks the binding commitments characteristic of formal alliances, making it vulnerable to changing regional dynamics or political shifts.

India’s deepening ties with Armenia follow a similar pattern of counterbalancing Türkiye’s influence. After its defeat in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Armenia turned to India to modernize its military and diversify away from Russian dependence.

Since 2022, India has provided roughly $2 billion in defense supplies to Yerevan, with an additional $600 million deal signed in 2024—making Armenia one of India’s leading arms importers.

Beyond military cooperation, the two countries are expanding the North–South Transport Corridor with Iran, a route connecting the Indian Ocean to Europe through the Persian Gulf and the Caucasus. But the proposed Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP), which would link Azerbaijan directly to Türkiye, removes those plans to a large extent.

For New Delhi, both Armenia and Cyprus serve as pivotal gateways in its effort to counter Türkiye’s reach, one in the Caucasus, the other in the Mediterranean.

Türkiye’s “Asia Anew” strategy and its expanding presence in the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Horn of Africa have challenged India’s traditional comfort zone in the region.

What began as Ankara’s search for diversified partnerships has evolved into a strategic competition that now spans from the Indo-Pacific to the eastern Mediterranean as a result of ideological tensions.

India’s response of reinforcing ties with Cyprus, Greece, and Armenia reflects an enduring strategic logic rooted in Kautilya’s ancient principle: neighbors are rivals, distant states are allies.

However, cooperation between the two emerging powers is not beyond reach. Should New Delhi show a willingness, Ankara would gladly stand on the side of partnership and stability—particularly given Türkiye’s openness to closer engagement with India and its vast Muslim community.