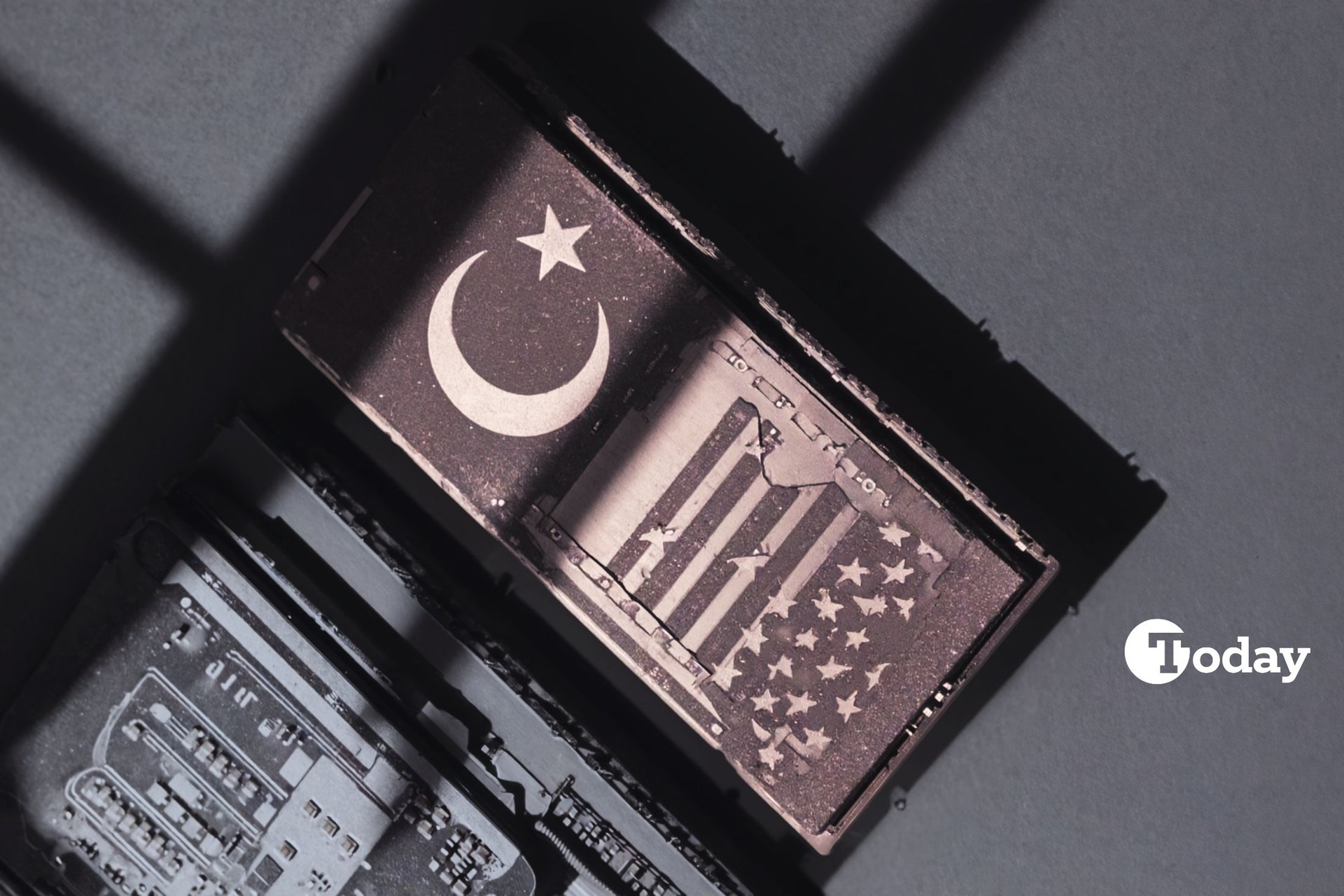

Ankara’s decision to lift additional customs duties on several U.S.-origin products marks a notable shift in Türkiye’s trade policy just days before President Recep Tayyip Erdogan sits down with U.S. President Donald Trump on Sept. 25.

The Ministry of Trade confirmed the change through the Official Gazette, stating that the “additional financial obligations” introduced in June 2018 would no longer apply. At the time, those tariffs were a direct response to Washington’s duties on Turkish exports. The move, now reversed, is widely interpreted as a goodwill gesture and a signal that Ankara hopes to steer relations onto more stable ground.

Officials expect the bilateral talks to cover a broad spectrum, from defense cooperation and regional security to potential investments. Yet the immediate focus is likely to be the commercial dimension of the relationship, especially as both governments have set a target of $100 billion in annual trade.

Relations with Washington have long carried symbolic and political significance in Türkiye. Since the early 1950s, successive governments in Ankara have used the perception of strong ties with the United States as a marker of political legitimacy.

But translating political alignment into economic benefit has been less straightforward. For much of the Cold War, the partnership was dominated by security concerns, with NATO forming the backbone of the relationship. Türkiye, as a frontline state against the Soviet Union, bore significant burdens, often acting as the “giving side” in alliance commitments without securing equivalent economic returns.

When Trump pressured NATO countries with military spending requirements, for instance, Türkiye was already meeting all the criteria. That period has changed and reset the relations between many countries and the U.S., as well as the nature of U.S. global trade strategies, where tariffs and transactional deals are increasingly defined by Washington’s approach.

Although Ankara has often played the East bloc as a counterbalance card, obstacles have consistently limited the flow of investments it sought from countries like China, among them the Uyghur cause coming first. Meanwhile, in terms of trade, Turkish business circles have never abandoned their balanced trade ties with the European Union and the United States.

Speaking at a Turkish investment conference in New York organized by the Türkiye-U.S. Business Council on Monday, Erdogan said he believes Ankara and Washington will reach a $100 billion trade target with the support of the private sector and new investment initiatives.

Türkiye-U.S. Business Council (TAIK) Chairman Murat Ozyegin recently reported that current bilateral trade, including services, stands at roughly $45 billion.

Similarly, DEIK Chairman Nail Olpak emphasized the exclusivity of the goal, noting that only about 10 countries in the world conduct business with the United States at such a scale. Türkiye’s inclusion in this narrow circle would elevate its economic profile but requires sustained political will and structural reforms.

A comparison with South Korea offers insight. Like Türkiye, Seoul is a close U.S. ally with a history shaped by security considerations. Yet South Korea has leveraged the relationship to move into high-tech industries, joint defense production, and strategic technology partnerships. The result has been a more balanced relationship that generates long-term economic resilience.

For Türkiye, the challenge is to replicate this trajectory. Simply importing more goods or exporting larger volumes will not create sustainable value. Instead, the emphasis must shift toward sectors like advanced manufacturing, chip production, and joint research, which would both diversify Türkiye’s economy and deepen strategic ties with the U.S.

The best field for this type of initiative seems to be the defense industry.

Speaking on Monday, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan urged the United States to eliminate obstacles hampering bilateral defense cooperation, emphasizing that such restrictions undermine the spirit of the NATO alliance between the two countries.

The experience of Gulf states highlights both the potential and the pitfalls of transactional trade with Washington. In 2016, Trump secured massive arms deals with Saudi Arabia, initially valued at $300 billion and later expanded to more than $1 trillion across the region. Qatar and other states sought to complement these defense purchases with technology and industrial cooperation, pushing for joint projects in chip manufacturing and industrial plants.

Türkiye now faces a similar strategic choice. Aircraft purchases and other high-profile deals may serve as quick wins, but they will not by themselves create lasting economic benefits. Unless paired with technology transfers and industrial investment, such arrangements risk reinforcing dependence rather than reducing it. Ankara’s ability to negotiate a balanced package—one that brings both immediate trade gains and long-term industrial development—will determine the sustainability of any breakthrough in US-Turkish economic relations.

The Gulf countries knew how to leverage these massive investments and others well, gaining important privileges such as the UAE's access to AI chips.

Unlike South Korea's model, the Gulf countries did not settle for just massive investment deals. Instead, they encouraged and undertook investments that would provide the infrastructure for high technology, from human resources to education.

Building such a framework requires more than trade deals—it depends on long-term investment in technology and human capital. Joint production of advanced products, student exchange programs, and doctoral-level training in the U.S. could form the basis of a sustainable model.

China offers an instructive case. Over the past two decades, Beijing has consistently sent thousands of students and researchers abroad, many of whom returned to drive domestic innovation in areas such as artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and green technology. Türkiye, with its young population, could benefit from a similar approach, provided institutional support is put in place.

The absence of this dimension risks locking Ankara into patterns of the past: large-scale purchases of defense or aviation products that expand trade figures but fail to create local capacity. Without access to the theoretical knowledge and industrial know-how behind the products, Türkiye remains dependent on external suppliers.

While institutional frameworks are central to durable cooperation, personal relationships between leaders have sometimes accelerated deals. Trump’s own record shows how unconventional diplomacy can bypass bureaucratic obstacles, as seen in his dealings with Britain and several Gulf states.

In Türkiye’s case, the personal rapport between Erdogan and Trump may ease immediate tensions and unlock opportunities for new agreements. Yet reliance on leader-to-leader ties carries risks. Structural changes—whether in Washington or Ankara—can quickly upend arrangements not grounded in institutional commitments. For Türkiye, building a durable economic partnership with the U.S. will require a balance between personal diplomacy and broader institutional frameworks.