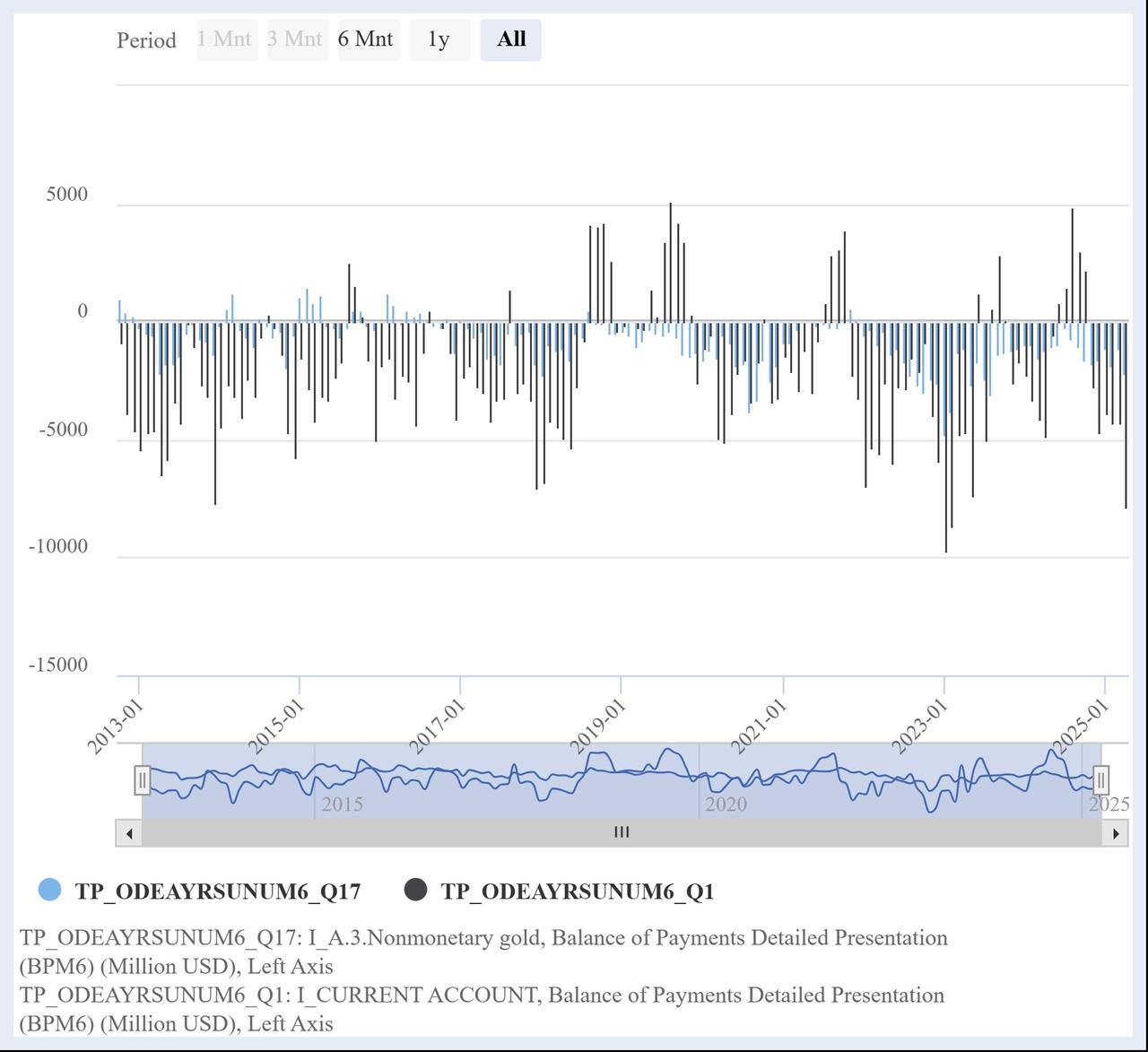

Türkiye's widening current account balance between January and April, which deepened to $20.3 billion from $14.5 billion a year earlier, has brought renewed attention to the country’s substantial gold imports, many of which remain outside the reach of the formal banking system.

The distinct Turkish tradition of "saving under the pillow"—a term referring to keeping valuables like gold at home—often comes into play during times of economic crisis, when the government calls on citizens to spend their savings to help revive the economy.

The deficit between gold imports and exports contributed $6.27 billion to the current account gap, increasing pressure on Türkiye’s external spending.

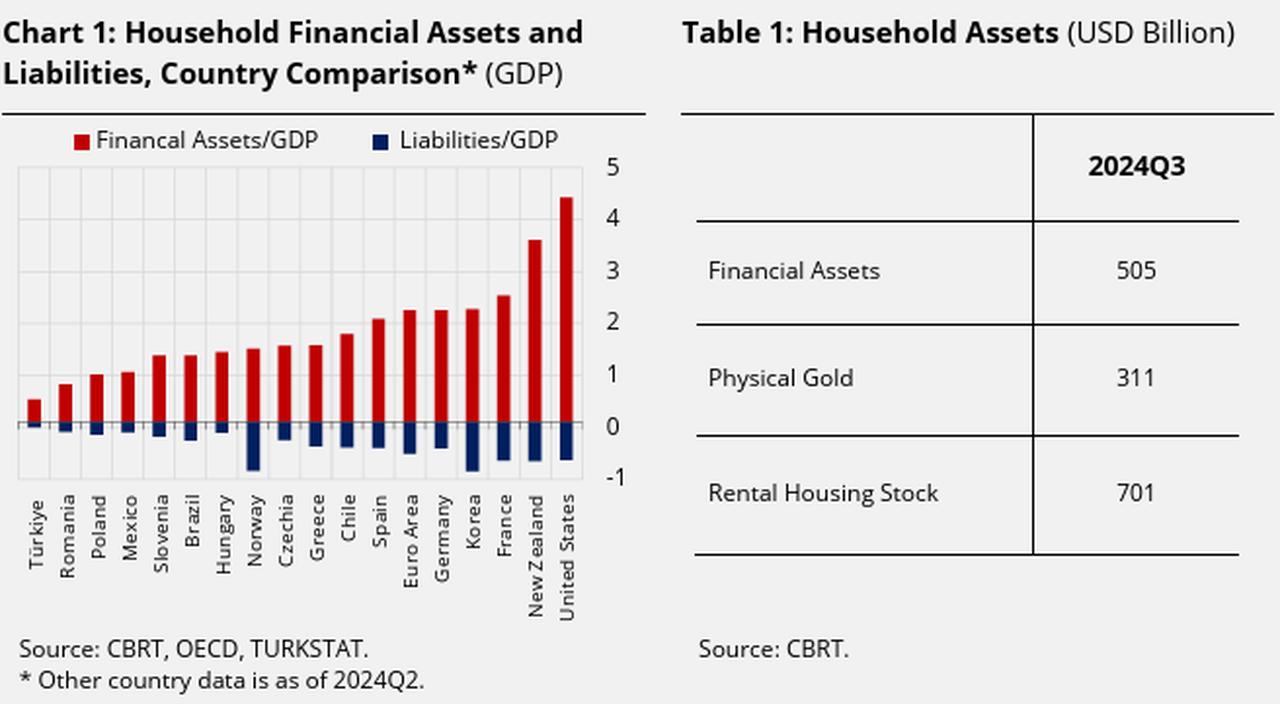

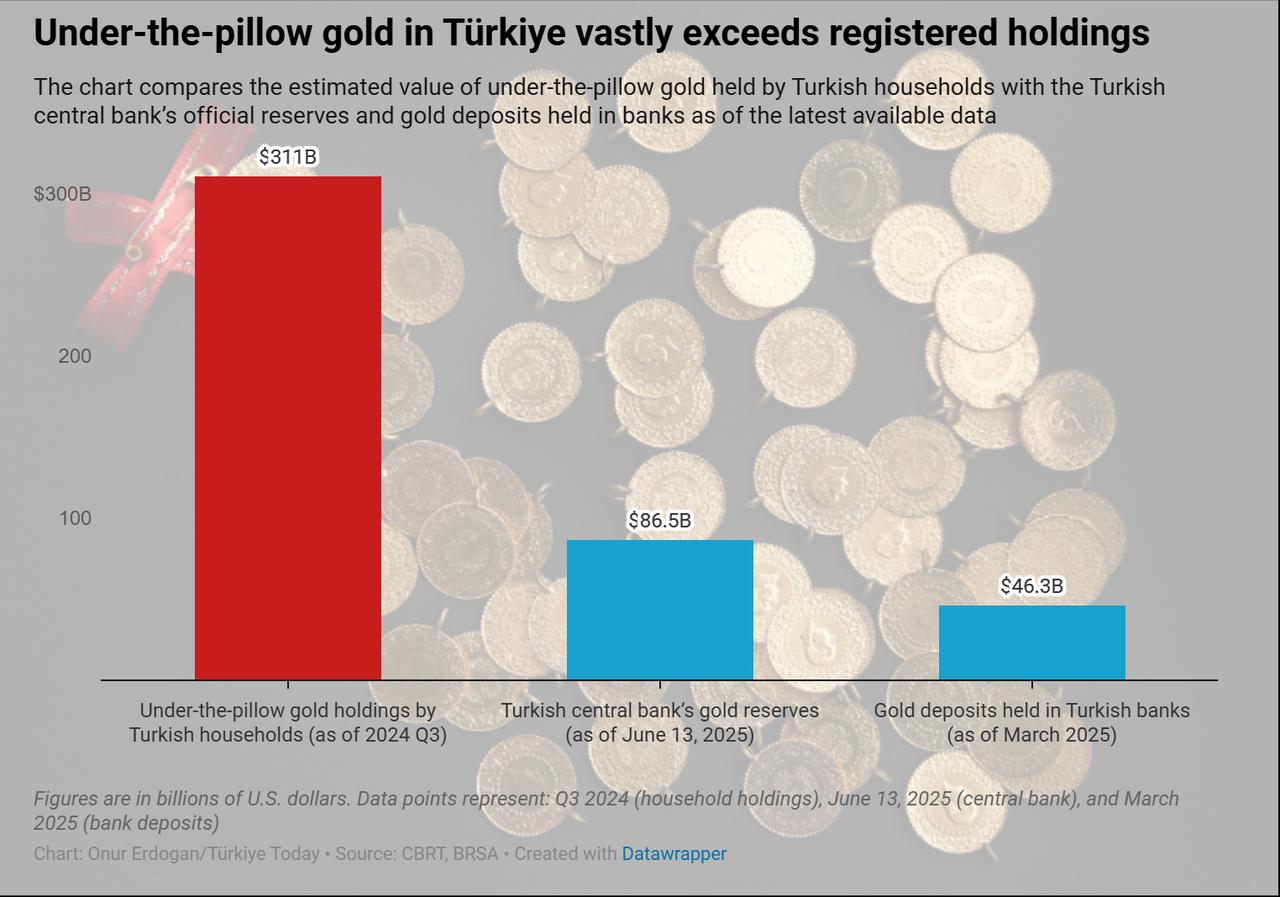

According to the Turkish central bank’s estimates, which are calculated by adding the current quarter’s gold production and imports to the previous period’s stock and subtracting gold exports, households held approximately $311 billion worth of unregistered physical gold as of the third quarter of 2024. Commonly referred to as “under-the-pillow” gold, this vast stockpile lies largely outside the official financial system.

This amount far surpasses even the central bank’s own gold reserves, which stood at $86.54 billion as of the week ending June 13. It also significantly exceeds the ₺1.83 trillion ($46.26 billion) in gold deposits recorded in Turkish banks as of March.

According to the World Gold Council's 2024 estimates, the total volume of gold in the Turkish economy exceeds 4,500 tonnes, with the majority held by households.

The reasons behind Türkiye’s massive under-the-pillow gold holdings are varied but interconnected. One of the most significant contributors is the country’s enduring tradition of gifting, saving, and investing in gold—particularly in the form of jewelry. This cultural norm is deeply embedded in social life, where gold serves both symbolic and financial functions in weddings, religious ceremonies, and as a trusted form of family savings.

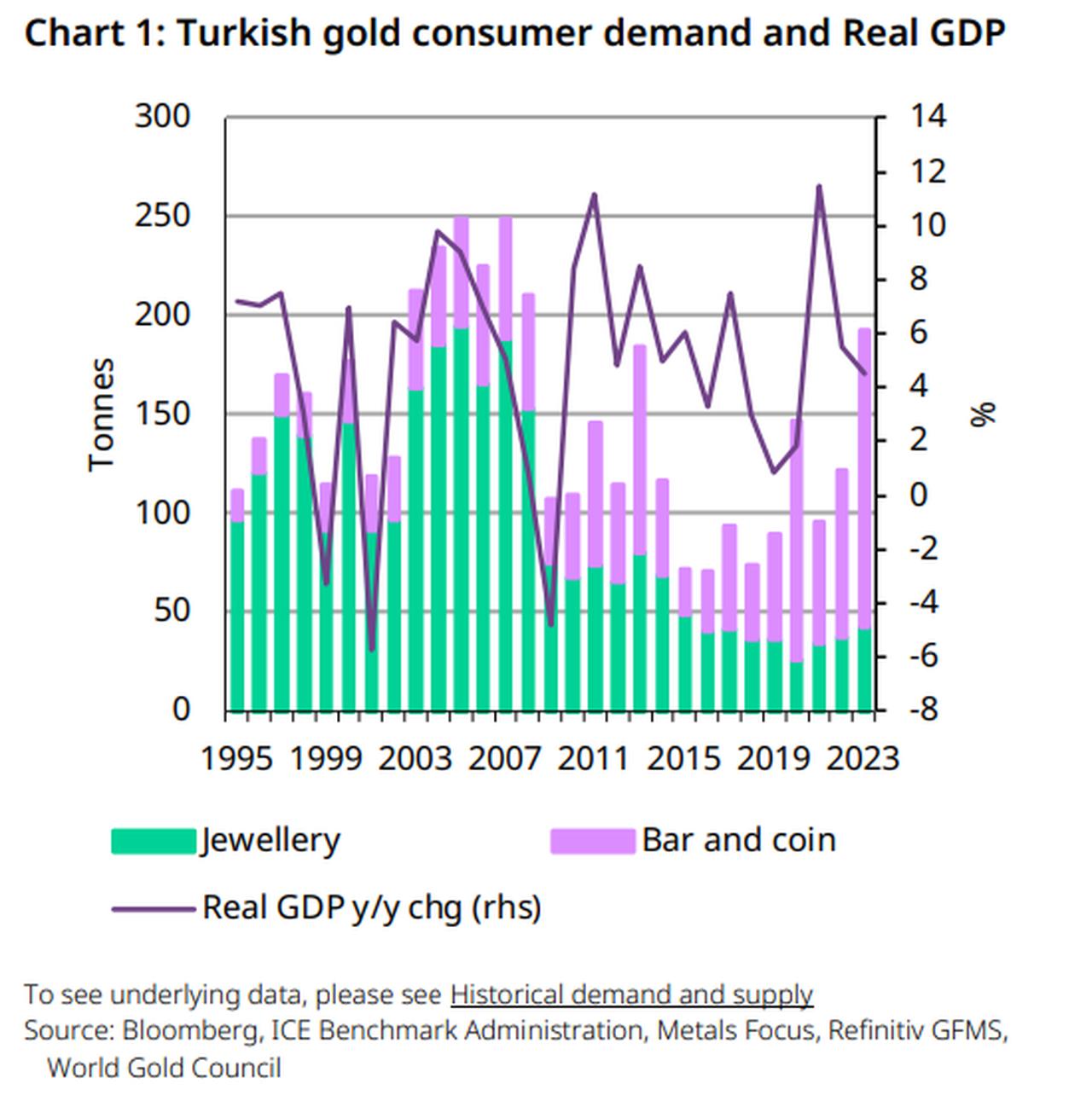

According to the World Gold Council, Türkiye was the fourth-largest gold jewelry market globally in 2023, behind China, India, and the United States, with annual demand totaling 42 tonnes. Over the last five years, annual jewelry demand has averaged 35 tonnes, and 41 tonnes over the past ten years.

Türkiye’s gold jewelry demand remained structurally strong throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, consistently exceeding 150 tonnes annually, largely supported by relatively affordable gold prices and steady economic growth. Demand peaked in the early 2000s, aligning with a period of double-digit real GDP expansion.

Following 2007, however, jewelry consumption began a steady decline, falling below 100 tonnes by the 2010s. In contrast, demand for bar and coin—typically associated with investment motives—remained more resilient, and in some years even increased. The divergence between jewelry and investment-oriented purchases became more pronounced in recent years, particularly as macroeconomic instability intensified.

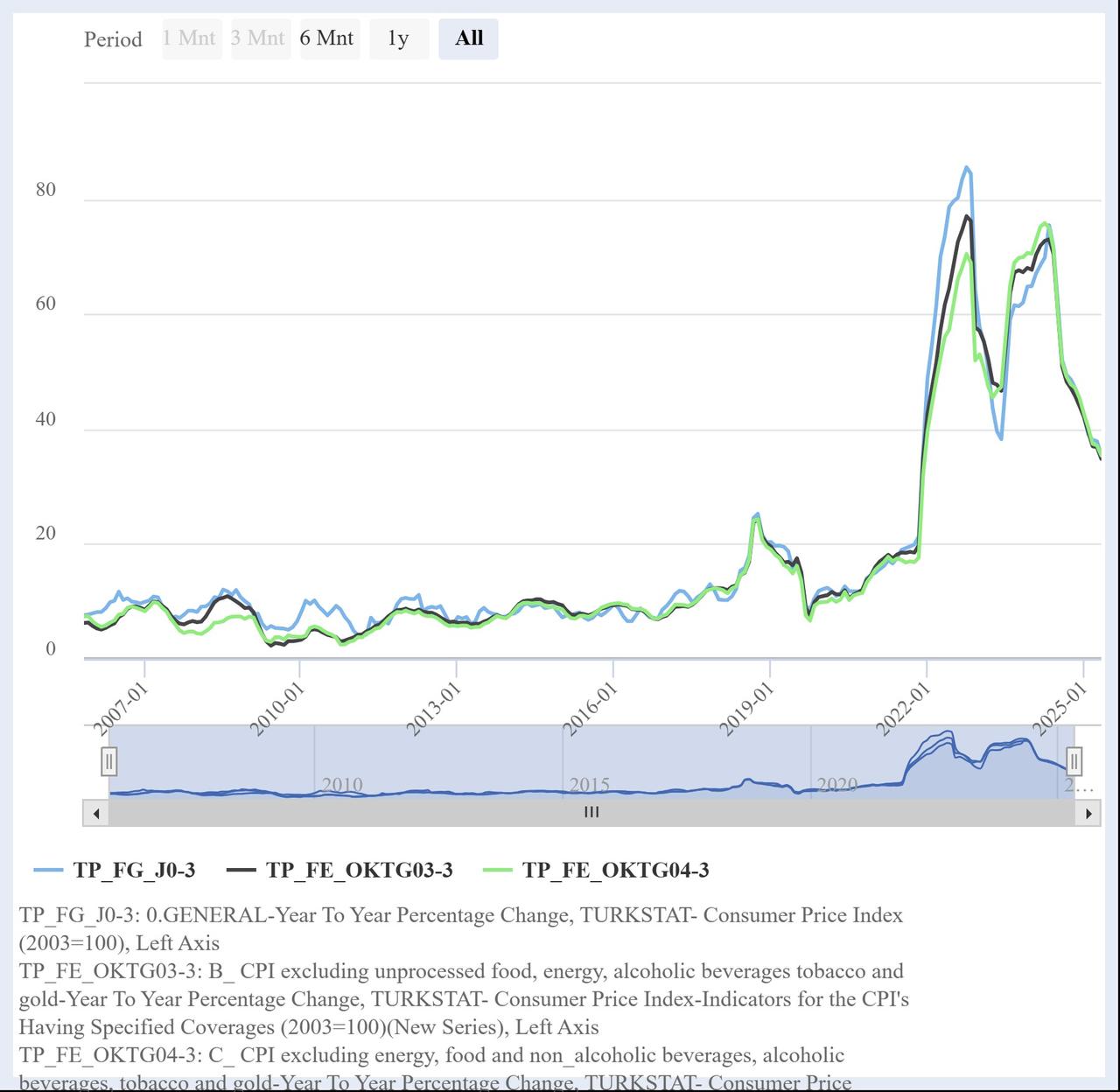

With persistent inflation and a weakening Turkish lira eroding trust in the national currency, households increasingly shifted their savings toward physical gold. This trend favored bars and coins over traditional jewelry, especially after Türkiye's inflation rate peaked at 85.51% in October 2022, according to official data.

Still, cultural preferences remain influential. In the final quarter of 2023, Türkiye recorded its highest gold jewelry demand for a fourth quarter since 2016. This surge was primarily driven by households seeking a tangible hedge against inflation and currency depreciation. Rather than opting for formal investment products, many preferred jewelry as a practical, wearable form of savings, allowing both value preservation and direct control over personal wealth.

Despite rising global gold prices, jewelry consumption has remained structurally high, reflecting its resilience not only as a cultural artifact but also as an informal investment tool. As gold continues to fulfill this dual role, households increasingly view jewelry as a hedge against financial volatility—reinforcing their longstanding preference for tangible, personally held assets.

Another key motivation behind Türkiye’s widespread preference for holding physical gold is the desire to avoid taxation on deposit interest and large financial transactions. Interest income on bank deposits is subject to withholding tax, and high-value banking activities may trigger regulatory reporting. In contrast, gold purchased and held privately—especially outside the banking system—remains largely beyond the reach of tax authorities. This makes gold not only a stable store of value but also a discreet way to preserve wealth.

This preference has been reinforced by the introduction of a 0.2% transaction tax on gold purchases made through banks as of March 17, 2025. Since such trades are treated as foreign exchange transactions, they are now subject to additional costs. Moreover, the significant difference between banks’ buying and selling prices discourages many from using formal channels, pushing them further toward physical holdings.

Most recently, as part of efforts to curb tax evasion and money laundering through gold transactions, Türkiye had enforced a rule in 2024 that requires customers to present identification for jewelry purchases exceeding ₺185,000 (approximately $5,274). In addition, the Treasury and Finance Ministry banned all sales of uncertified cut gold bars in March, aiming to prevent untraceable transactions and tighten oversight of informal gold trade.

Economist Mahfi Egilmez offers insight into why past efforts to draw household gold into the formal financial system have seen limited success. He distinguishes between two types of informal wealth: unregistered income, which directly impacts gross domestic product (GDP) calculations, and legally acquired but system-external assets, such as physical gold and foreign currency held privately, often outside the reach of institutions.

These hidden reserves often act as a financial buffer. During periods of economic distress, individuals and businesses liquidate part of their gold or foreign exchange holdings to meet urgent needs. Once stability returns, they tend to replenish these reserves gradually, usually through informal, undocumented means. This ongoing cycle of withdrawal and replenishment reflects a widespread strategy for managing risk, especially in environments of financial volatility.

This behavior also helps explain the recurring appearance of unexplained capital inflows in Türkiye’s balance of payments, recorded under the item “Net Errors and Omissions.” These inflows indicate that a considerable share of economic activity occurs beyond official monitoring, yet still contributes to stabilizing the economy during times of stress.

Off-the-record reserves have played a crucial role in helping Türkiye absorb repeated economic shocks—from currency depreciation to inflation—without triggering systemic collapse, Egilmez adds. Such wealth provides liquidity and flexibility when formal mechanisms fail or fall short.

On the other hand, according to Egilmez, their continued exclusion from the official financial system represents a missed opportunity. If even part of these holdings were redirected through banks or investment channels, they could support long-term capital formation, strengthen monetary control, and expand credit availability, contributing to more sustainable macroeconomic stability.

Efforts to incorporate Türkiye’s vast household gold holdings into the formal banking system have spanned several decades, reflecting successive governments’ desire to mobilize this dormant capital.

According to gold markets expert Huseyin Deniz, the earliest major attempt to bring household gold into the financial system dates back to the early 1980s, under Prime Minister Turgut Ozal. As part of his liberalization reforms following a period of economic instability, Ozal’s government introduced proposals to encourage citizens to deposit their physical gold in banks. The plan aimed to convert under-the-pillow gold into interest-bearing deposit accounts. Depositors would be repaid in foreign currency based on the prevailing gold price at maturity, or in Turkish lira if withdrawn earlier.

However, concerns soon emerged about liquidity risks. Policymakers feared a potential crisis if all depositors demanded physical gold at once, particularly if the collected gold had already been sold abroad to obtain foreign currency. As a result, the initiative remained limited in both scope and implementation.

Decades after the first initiatives, the push to formalize gold holdings was revived during the AK Party era. In late 2016, amid sharp depreciation of the Turkish lira and growing dollarization, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan publicly urged citizens to convert their foreign currency and under-the-pillow gold into Turkish lira or deposit them in banks. This call was framed not only as an economic necessity but also as a patriotic responsibility to support the national economy. While parts of the public responded, longstanding structural issues—such as high inflation, currency volatility, and limited trust in financial institutions—prevented a large-scale shift of gold into the formal banking system.

In 2017, the Treasury and Finance Ministry launched the first Gold Bond and Gold-Backed Lease Certificate, enabling citizens holding physical gold to earn returns on their holdings.

In 2022, the Turkish government accelerated its efforts to channel physical gold into the banking system by launching the Gold Conversion System in 2022. Introduced by the Treasury and Finance Ministry, the program allows citizens to deposit their gold at contracted jewelers, which is then securely and transparently transferred into the financial system. These deposits can be converted into gold-backed bank accounts or certificates, helping individuals preserve savings while drawing unregistered gold into the formal economy.

Türkiye's equity market, Borsa Istanbul, also unveiled a system in 2022 that allows investors to trade gold certificates backed by physical reserves. Since then, interest has grown steadily—particularly in 2025—with certificate values surging 54.6% year-to-date, outpacing the 42.85% gain in physical gram gold. Zero tax, narrow buy-sell spreads, and exemption from storage fees make certificates a more cost-effective option. They are redeemable starting at 50 grams and insured up to 1 kilogram, offering greater protection than regular bank deposits.

These efforts still appear insufficient to meaningfully alter the deeply rooted behaviors of Turkish households, who continue to prefer holding gold outside the formal financial system, driven by a mix of cultural norms, practical concerns, and structural economic uncertainties.