The British TV series Tutankhamun has reignited global interest not just in ancient Egypt but in the colonial legacies shaping archaeological narratives. A recent study from Türkiye examines how the series reflects and critiques the West’s ongoing cultural dominance in the field.

The series, aired by ITV in 2016, dramatizes British archaeologist Howard Carter’s discovery of Pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb. But beyond the romance and adventure, the production subtly reaffirms colonial-era hierarchies, according to Oytun Dogan's detailed media anthropology analysis.

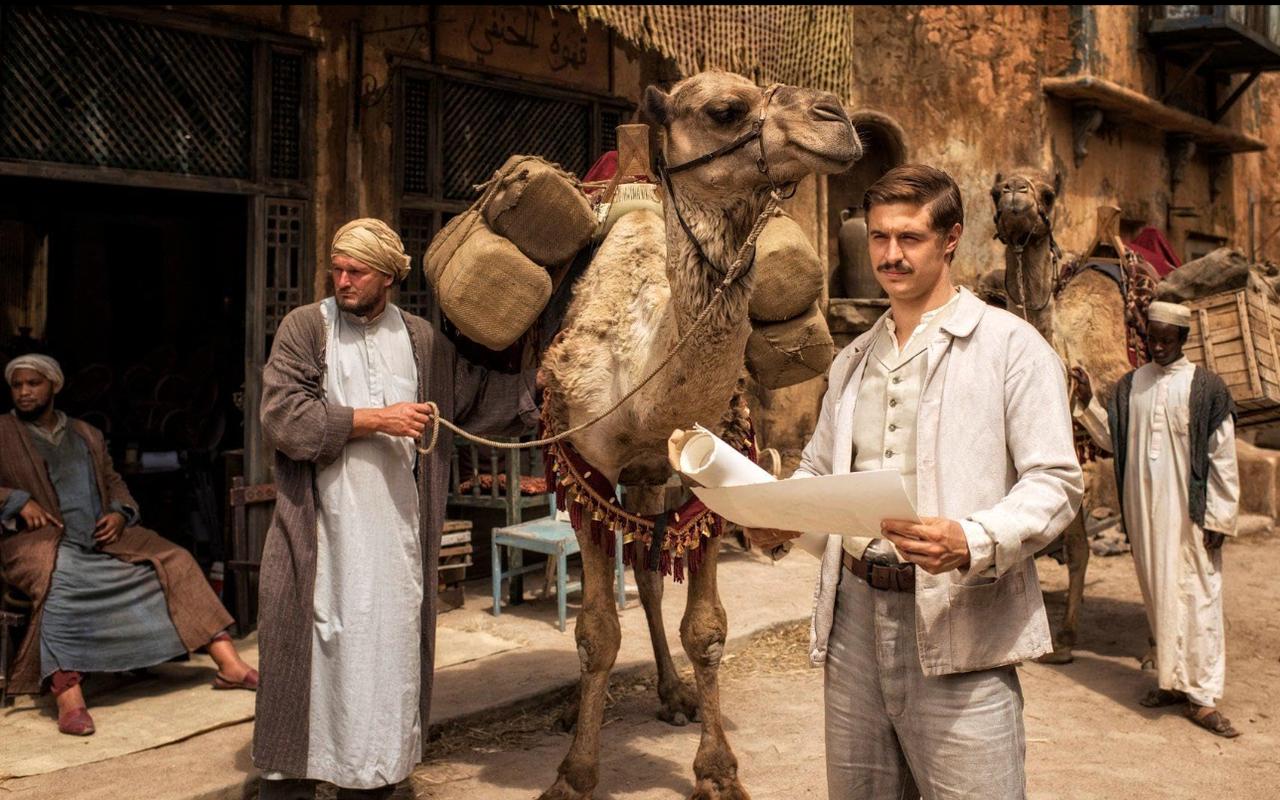

Through a semiotic lens, the study dissects key scenes and symbols—white tents in the desert, Carter’s upright stance before Egyptian officials, and muted local voices—to reveal the visual grammar of domination. Carter, though cast as a well-meaning hero, embodies the mythologized Western savior archetype.

Despite being set in Egypt, the locals in the series appear as background figures. Their language is subtitled or ignored, their names are often unmentioned, and their knowledge is disregarded.

Even the Egyptian Antiquities Service is portrayed as an obstacle rather than an equal authority.

Dogan argues this isn't merely artistic license—it’s a continuation of colonial storytelling where the West "discovers" and controls the past, even as postcolonial nations reclaim their heritage.

One key episode captures a heated debate between Carter and Lacau, head of Egypt's Antiquities. Lacau insists that Tutankhamun's treasures belong entirely to Egypt, reflecting growing national consciousness after World War I. The British characters’ frustration signals the fading era of imperial entitlement.

Today, those same artifacts sit in institutions like the British Museum or the Louvre, continuing a legacy of cultural imbalance that Tutankhamun indirectly upholds.

The analysis goes further to argue that Tutankhamun is not merely entertainment but a modern myth that supports a Western-centric view of historical knowledge. British media, the study claims, repackages colonial archaeology into palatable, nostalgic narratives, reinforcing imperialist ideologies under the guise of drama.

And the framing leans Western: Lacau is cast as bureaucratic and obstructive, Carter as the noble truth-seeker. The series thus dramatizes, but does not dismantle, colonial hierarchies.

The visual decisions—lighting, costuming, and language choices—intentionally blur the line between fact and fiction. Arabic dialogue is often untranslated, symbolic of how local voices were historically ignored or overwritten in archaeological documentation.

The final episode depicts Egyptian protesters demanding that Tutankhamun's belongings remain in Egypt, symbolizing a broader movement to reclaim national identity and historical agency. The study positions this shift as a turning point, where the subtext of cultural resistance surfaces within popular media.

The study concludes that popular culture is a powerful site of ideological production. It warns that without critical engagement, media like Tutankhamun risk becoming a tool of soft power, entertaining global audiences while quietly reinforcing Western historical dominance.

The representation of Egypt's resistance and cultural awakening, though present in the show, is filtered through a Western lens, underscoring the urgency of media literacy and decolonized storytelling in archaeology.