The depiction of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) remains one of the most sensitive red lines in Islam, rooted not just in theology but also in the socio-religious context of the time of the birth of the religion. At the time, seventh-century Arabian society was saturated with idol worship. Religious life revolved around physical representations of deities, often in the form of statues or illustrations, which were used in rituals and veneration.

Against this backdrop, Islam introduced a radical shift. The new faith sought to dismantle these practices and reorient spiritual life around the concept of "Tawhid," the uncompromising oneness of God. The prophet explicitly forbade image-making of himself, as a safeguard against the resurgence of idolatry. His directive was practical, preventive, and shaped by the specific cultural threats.

At the heart of the issue is the Islamic view of "shirk" (associating partners with God), which is considered the gravest theological error. While other monotheistic traditions have tolerated or incorporated images into religious practice, Islam drew a much firmer line.

This distinction is not without historical justification. In various civilizations, images that began as symbolic representations often evolved into objects of worship. Islamic scholars and jurists viewed such trends as cautionary tales and designed strict boundaries to prevent similar developments within their own tradition.

Beyond legal or textual prohibitions, there is also a deeper concern: how imagery shapes collective emotion and memory. In Islamic thought, visual depictions can serve as a gateway to unintended sanctification. Emotional attachment to an image, particularly one representing a revered religious figure, can, over time, shift into a form of veneration.

While the Quran does not explicitly ban all forms of imagery, it does describe idol-making as an act of ignorance and injustice. Muslims view depictions of Prophet Muhammad as a grave insult to themselves and a deliberate attack, as it’s known and kept clean for centuries.

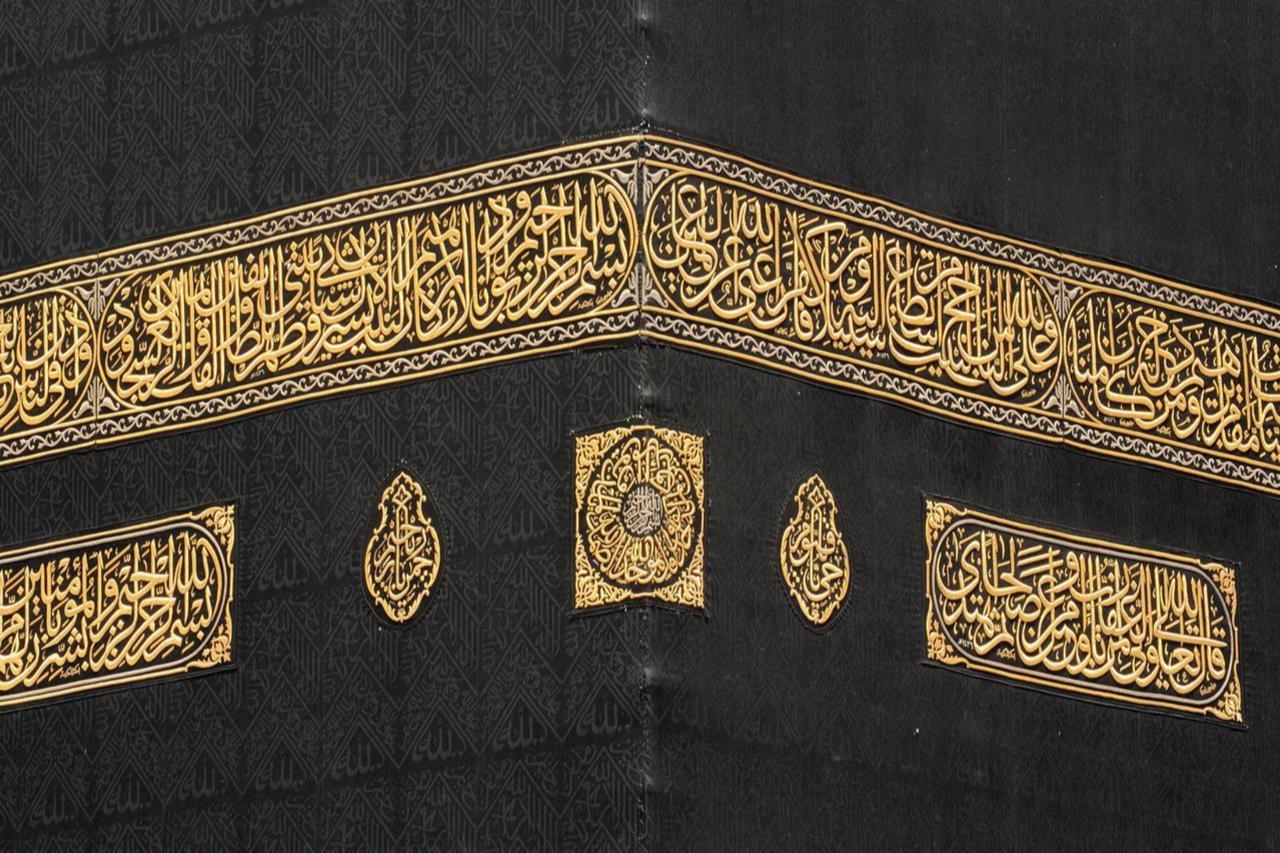

Despite the ban on imagery, Muslim culture honors the Prophet through alternative forms of reverence that align with religious norms. One such tradition is the "Hilye-i Saadet," an Ottoman-era art form that uses calligraphy to describe the prophet’s physical and moral attributes, often based on narrations from his companions.

These works, often framed and hung in homes, serve as a spiritual and aesthetic tribute without venturing into territory that could be interpreted as idolatrous. They reflect a broader Islamic approach: to preserve reverence while firmly avoiding deification.

On the other hand, in the few cases where depictions were made historically—mostly within certain strands of Shia Islam or Persian and Ottoman miniatures—the prophet was often shown with his face veiled or replaced with a symbol like light or flame. These exceptions were niche, meant for private devotional or artistic purposes, and never for public or satirical display.

Depicting the prophet is not just seen as a theological violation; it is also deeply hurtful to many Muslims on a personal level. Prophet Muhammad is not just a religious figure; he is a source of moral guidance, a model of compassion and justice, and a beloved figure whose name is invoked daily in prayers and greetings.

So when depictions occur—especially when they're perceived as disrespectful, such as in caricatures or satirical cartoons—many Muslims interpret them not merely as artistic expression but as an intentional provocation or mockery. This emotional bond explains why even Muslims who are not particularly observant may feel outraged by such imagery.

The prohibition on depicting Prophet Muhammad is not an arbitrary restriction nor merely a cultural preference. It is a theological stance informed by history, rooted in scripture, and shaped by a desire to protect the spiritual core of Islam.

It’s also important to note that the Muslim world is not monolithic. While the majority reject depictions of the Prophet, there are varying degrees of response. Some focus on education and dialogue to counter offensive images, while others call for legal or diplomatic action. A smaller minority may react violently, but their actions are widely condemned by mainstream Islamic scholars and communities.

The common thread across these responses is a shared understanding: that the prophet’s honor is sacred, and portraying him, even with good intentions, is seen as an unacceptable intrusion into what is considered holy ground.