Researchers working at El Gigante rockshelter in western Honduras have uncovered the earliest known evidence of avocado domestication, pushing back the timeline of arboriculture in Central America to nearly 11,000 years ago. Their findings suggest that local populations were managing avocado trees thousands of years before staple grain cultivation became dominant, reshaping ideas about early farming in the Americas.

The research, led by a multi-institutional team and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, analyzed more than 1,700 avocado remains—including seeds and rind fragments—from deeply stratified archaeological layers. Using 292 high-precision radiocarbon dates, including 56 on avocado remains, the team constructed a robust timeline of human-plant interaction at the site.

Measurements of seed size and rind thickness revealed a gradual but continuous trend toward larger, more robust fruits. Evidence of human-directed selection first appeared around 7,500 years ago. By 2,250 to 2,080 years ago, domesticated traits such as thicker rinds and larger seeds had become widespread

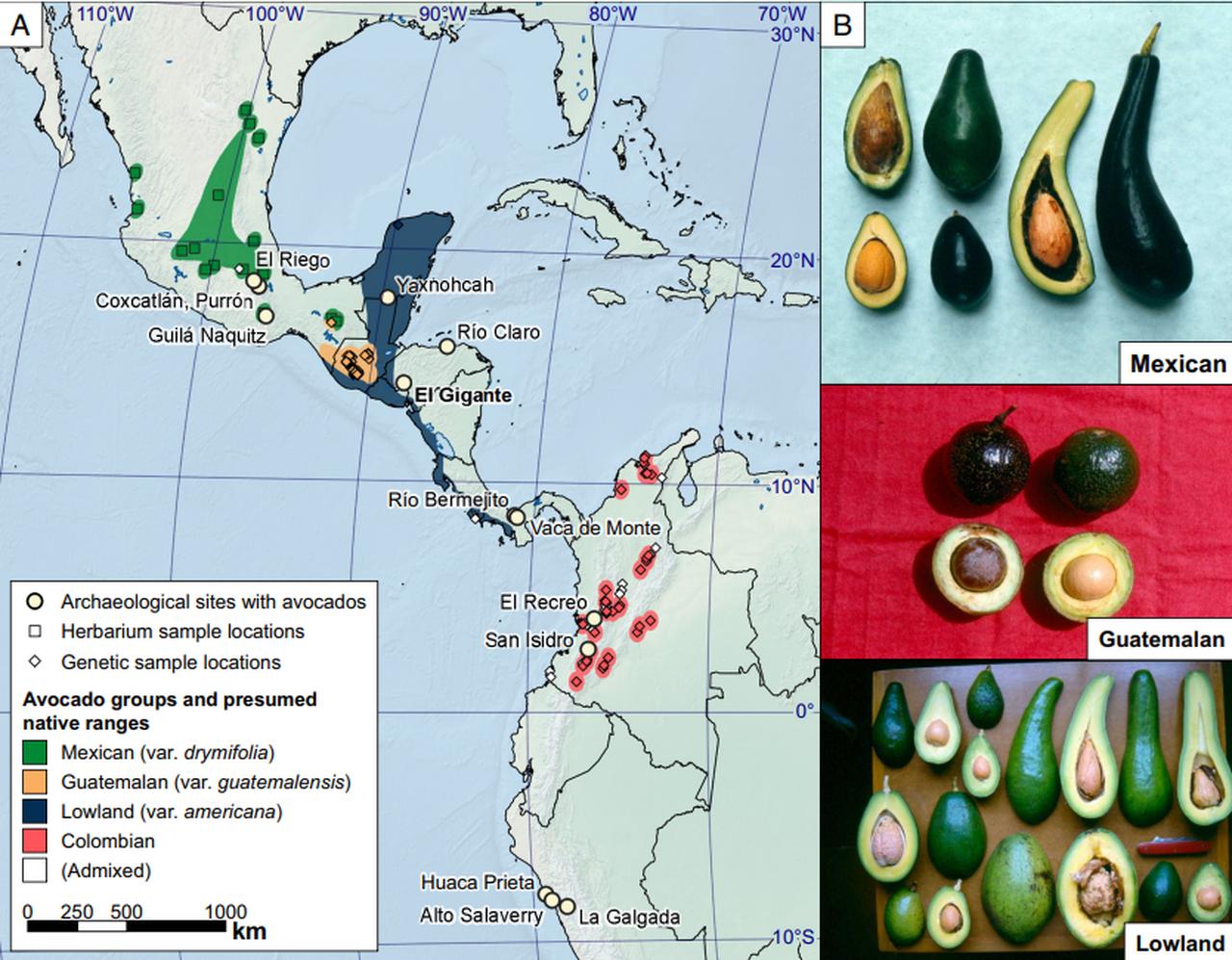

The study identifies the El Gigante avocados as most similar to the guatemalensis variety, which thrives in the highlands of Guatemala and Honduras. This variety is genetically linked to the popular Hass avocado, which now accounts for 90% of global production.

The findings suggest that the genetic roots of today’s commercial avocado industry lie not only in Mexico, as often assumed, but also deep in the forests of western Honduras.

Unlike in Asia, where tree domestication typically followed the establishment of annual grain crops, in Mesoamerica tree cultivation appears to have taken root first. At El Gigante, tree fruits such as avocado and wild squash dominate the early layers, while maize and beans only become prominent around 4,400 years ago. This pattern points to a long-standing tradition of arboriculture that predates intensive field agriculture.

The study not only rewrites the history of avocado farming but also holds lessons for the future. The genetic diversity found in ancient avocado varieties may offer solutions for modern agriculture, especially as climate change threatens today’s narrow gene pool dominated by clonal Hass trees. As global demand for avocados grows—production reached around 9 million tons in 2022—these ancient seeds may hold the key to building a more resilient future for the fruit.