At Sefertepe, one of the easternmost sites of the Tas Tepeler (Stone Mounds) project in the Viransehir district of Sanliurfa, archaeologists have uncovered 8,500-year-old human faces carved on stone and engraved on a tiny bead. The new finds, which belong to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period dating back roughly 8,500 years, open a rare window onto the symbolic world of this settlement and set Sefertepe apart from better-known sites such as Gobeklitepe, Karahantepe and Sayburc.

One of the most striking discoveries of the 2025 excavation season is a stone block that carries two different human faces side by side. According to the excavation team, one face is rendered in high relief, while the other appears in low relief, so the two images emerge from the same block with different depths.

These contrasting carving techniques are described not only as a technical choice but as a feature that may point to two separate identities or states being expressed on a single surface. Archaeologists underline that the style of these faces differs from the human depictions that have become familiar from other Tas Tepeler sites, and that this contrast strengthens the picture of local stylistic diversity within the wider project area.

The Tas Tepeler project, carried out under the leadership of the General Directorate of Cultural Assets and Museums over the past five years, focuses on early Neolithic settlements across the northern reaches of the Firat and Dicle river basins, especially around Sanliurfa. Researchers note that every newly uncovered carved stone or sculpture at Sefertepe helps them trace how local communities created their own visual language within this broader landscape.

Sefertepe is also known for its large number of small finds, especially beads, which the team describes as the most common artefact group at the site. From the first year of work onwards, excavations have produced beads made from a wide range of forms and raw materials.

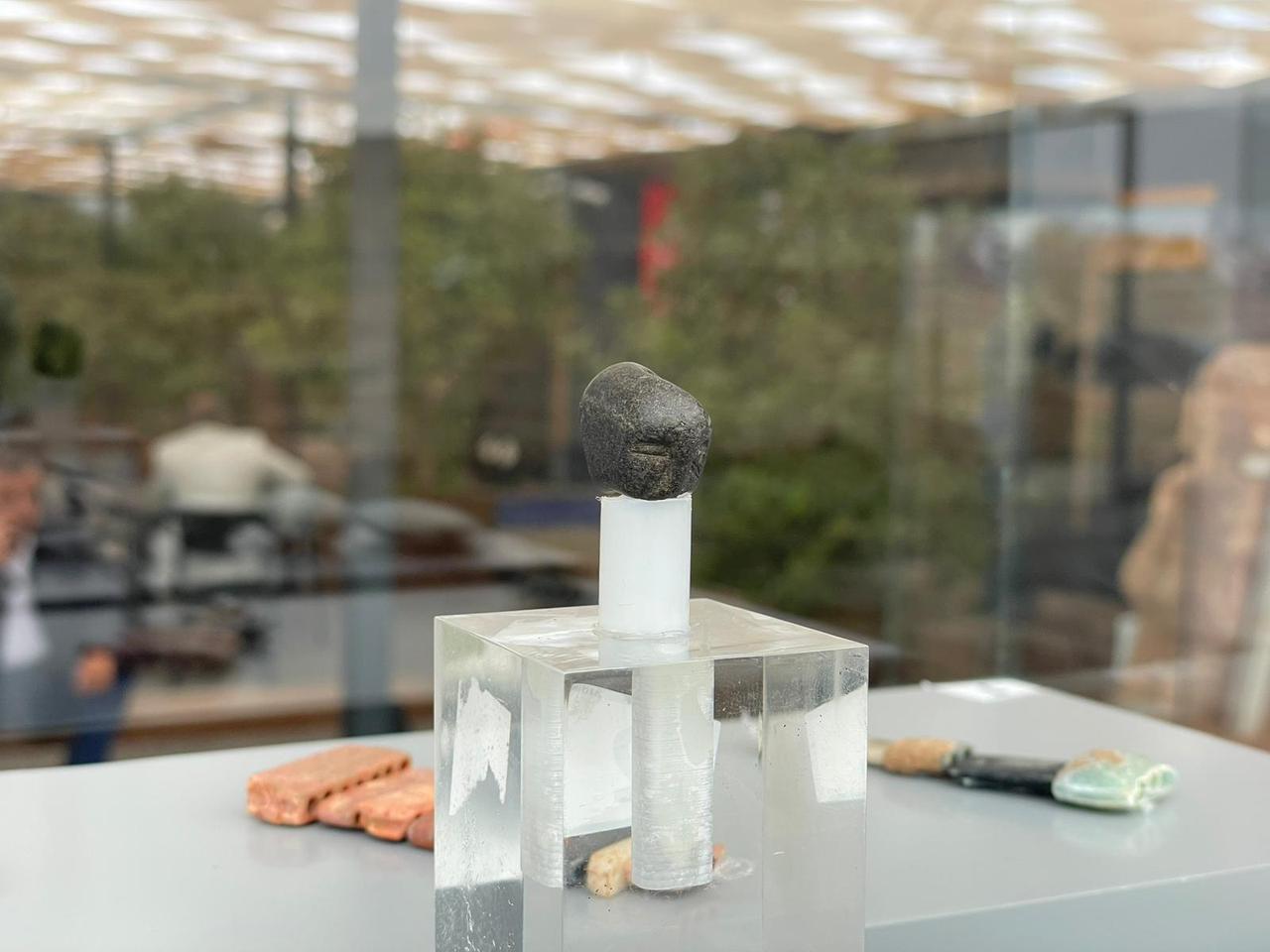

In 2025, one small but carefully worked piece has stood out: a black basalt bead bearing a double-faced human motif. This bead, which shows two faces on a single object, is presented as evidence of the community’s refined craft skills during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period.

Other beads found at Sefertepe were produced from materials such as jade, labradorite and limestone. The presence of jade and labradorite, which the team believes came from outside the immediate region, is interpreted as a sign that Sefertepe was not just an isolated village but part of a broader network of interaction.

Speaking to Türkiye Today, excavation director Associate Professor Emre Guldogan notes that among the small finds, the team has identified snake-head-shaped beads made from such non-local raw materials.

Guldogan explains that Sefertepe has now completed its fifth excavation season within the Tas Tepeler project and recalls that from the beginning, the team has followed a strategy that traces the continuation of an architectural complex belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period. He states that new areas have been opened in connection with an enlarging architectural complex, adding that this season has again produced dense bead finds, including a special double-faced human bead, alongside the newly discovered stone block with two carved human figures placed on a platform.

Sefertepe’s importance does not rest only on its carved faces and beads. Human remains have been known at the site since the very first excavation season, and they now form an important part of the discussion on Neolithic death practices.

In 2024, archaeologists documented 22 human skulls placed in an orderly way inside a single room. In this space, only two skulls retained a lower jawbone, and no other bones were found. The team has referred to this space as the “skull room,” and interprets it as an area where skulls were brought together and given a special status separate from the rest of the body.

North of this room, the situation changes. Here, seven different skulls were uncovered together with the rest of their skeletal remains. This contrast suggests that, within the same settlement, skulls could be separated from the body in some cases and kept intact with the skeleton in others. Researchers see this overlap as evidence for intertwined death rituals in which the selection and gathering of skulls played a key role in practices of remembrance, identity and relationships with ancestors.

Guldogan emphasizes that, together with other finds, Sefertepe is beginning to show parallels with settlements in the Dicle region and is helping to clarify relations between the Firat and Dicle basins. He underlines that, in this sense, the 2025 excavation season has produced important results for understanding connections across this wider geography.

The broader Neolithic context remains central to how archaeologists frame these results. They describe the Neolithic period as an era of major transformation in humanity’s shared past, when communities began to settle permanently and to produce food, setting in motion processes that still shape human life today.

Within this process, the northern parts of the Firat and Dicle rivers, especially the area around Sanliurfa, stand out as a region where cultural changes can be followed in striking detail. The Tas Tepeler project is presented as a long-term effort to reveal the early traces of civilisation in this landscape, by bringing together excavation, research and analysis over five years.

Project statements stress that archaeological and archaeometric work has already documented many aspects of Neolithic life, ranging from rituals and daily practices to subsistence strategies, domestication processes, architecture and production technologies. Officials state that the data gathered over the five years confirm how solid and realistic the project’s original goals were, and describe the results as revealing the earliest traces of civilisation “with a unique depth.”