A forgotten town from the Byzantine, also known as Late Roman or East Roman era, long preserved only in mosaic tiles and scholarly debate, has finally been rediscovered in southern Jordan. The town of Tharais, once featured on the renowned Madaba Mosaic Map, has been positively identified near the modern town of El-‘Iraq in the Karak Governorate, providing a new chapter in the archaeological and cultural history of the region.

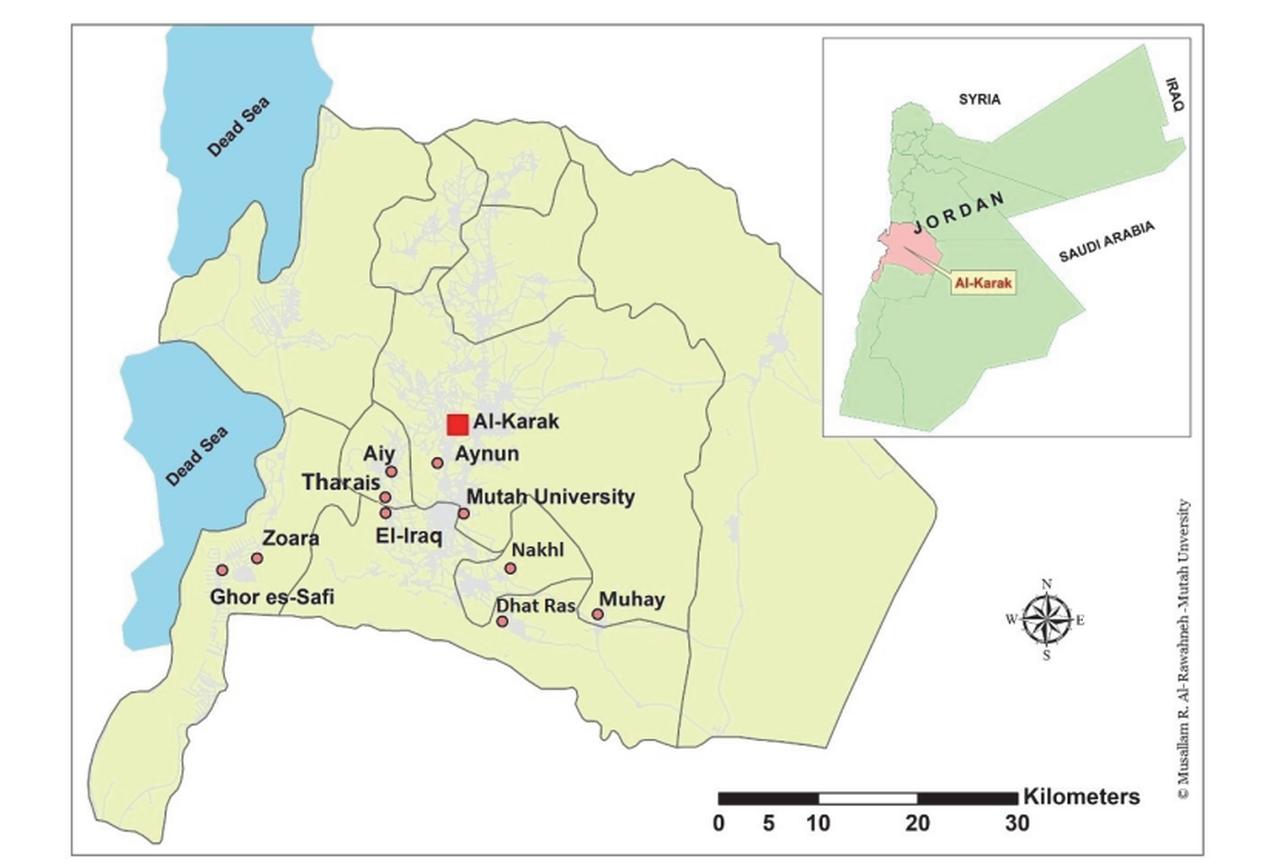

The multi-year field project, conducted between 2021 and 2024 by a research team led by Musallam R. al-Rawahneh, associate professor of archaeology and ancient Near Eastern studies at the department of archaeology and tourism at Mutah University, culminated in the successful location of Tharais based on archaeological surveys, historical analysis, and local insights. This site, buried for centuries, is now proving to be a significant link to the Byzantine civilization that once flourished across Jordan and the surrounding areas.

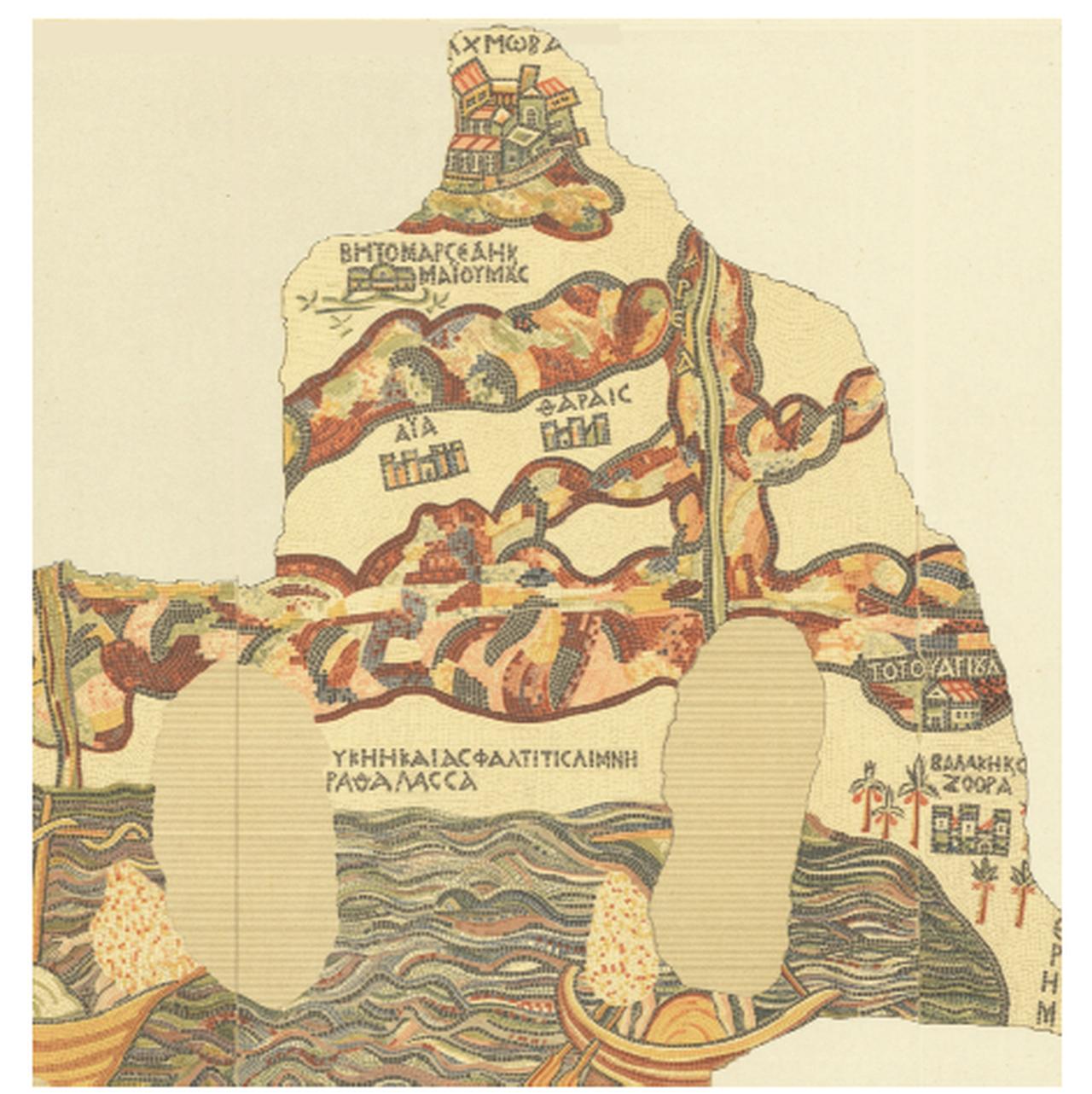

The Madaba Mosaic Map is a sixth-century floor mosaic found in the Greek Orthodox Church of St. George in modern-day Madaba, Jordan. Known as the oldest surviving map of the Holy Land, it illustrates numerous biblical and historical locations across Jordan, Palestine, and Egypt.

Among its many references, the map depicted the town of Tharais—until recently, its exact whereabouts remained a mystery. Scholars had debated its location for over a century, with earlier hypotheses pointing to areas as far as Dhat Ras. But thanks to a renewed wave of scholarly interest and advanced archaeological methods, the team narrowed down its search area based on the proximity to other known map references, notably the village of Ai (Ἀi).

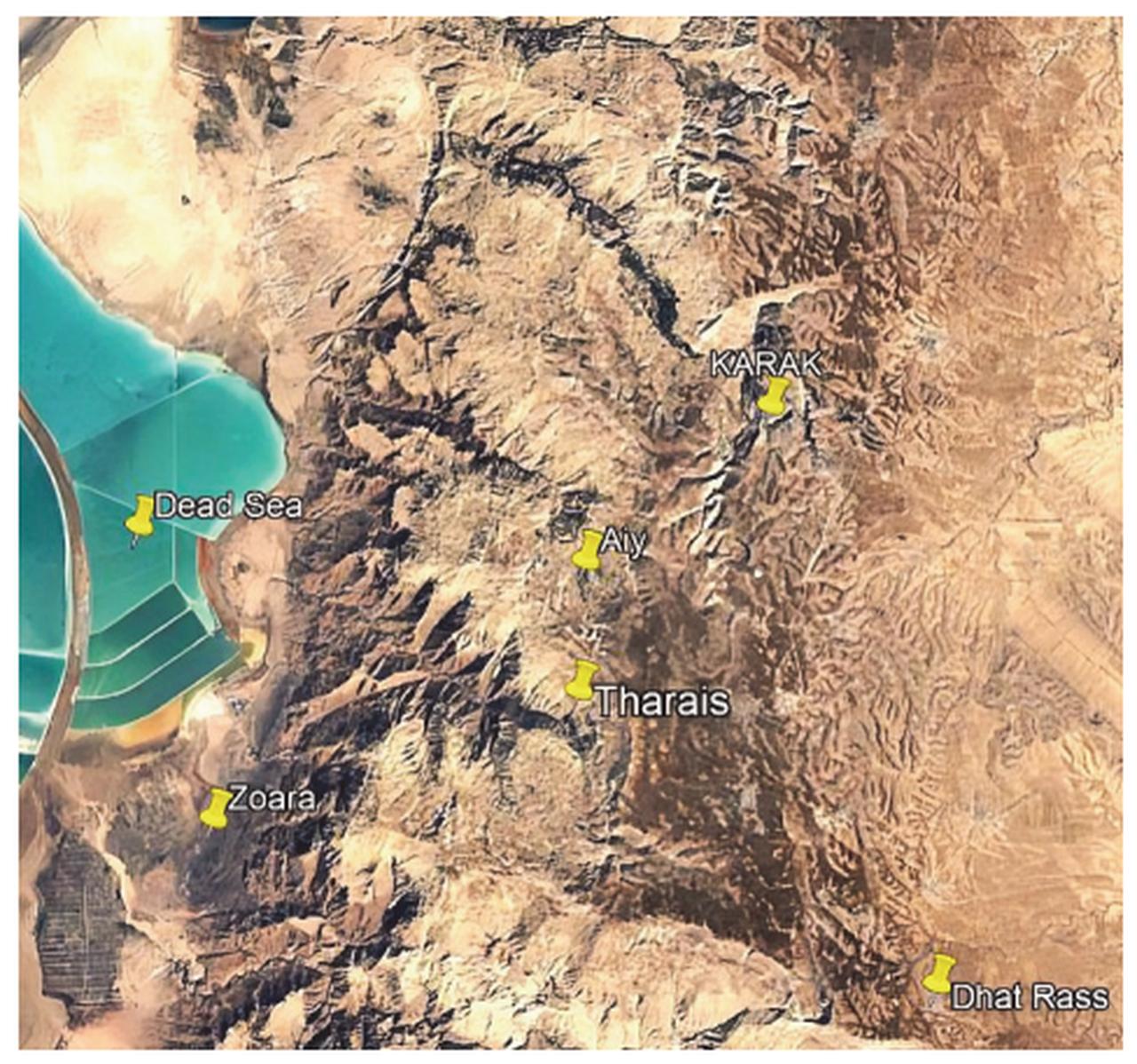

The turning point in the identification came during a field survey in the rugged landscape of western Karak. A gradual increase in Byzantine-era pottery shards and architectural debris near El-‘Iraq, especially on the northwestern edge, provided compelling evidence of continuous settlement from the Roman through Islamic periods.

The discoveries included fragments of mosaic floors, glassware, and various tools, but most notably, architectural features resembling a Byzantine basilica church. The remnants of a gateway, columns, mosaic flooring, and industrial installations such as an olive press all pointed to a vibrant community with both religious and economic significance.

Adding to the evidence were Greek and Latin funerary inscriptions unearthed in cooperation with international institutions from Spain and France. These inscriptions—dating from the fifth to seventh centuries A.D.—confirm the existence of a Christian community, aligning well with the site's suspected identity.

The geographical location of Tharais lends support to its dual role as a religious center and a waypoint on a key trade corridor. Positioned between the Moabite Plateau and the southeastern edge of the Dead Sea, it was strategically placed along the ancient Roman road networks connecting Zoar (modern Ghor es-Safi) to central Jordan.

“The prominence of Tharais on the Madaba Map and the discovery of a basilica church structure suggest that it served not only as an agricultural village but also as a sacred site and commercial rest stop,” says al-Rawahneh.

The presence of installations such as olive oil presses, watermills, and grape crushing equipment reinforces the assumption that Tharais was economically self-sustaining. Meanwhile, the decorative elements of triglyphs and mosaic tiles suggest a fusion of local and classical architectural styles.

What makes this discovery particularly striking is how closely the features of the site match its representation on the Madaba Mosaic Map. The spatial arrangement of ruins, gate-like structures, and even the presence of towers near the entrance align with the map's depiction of Tharais.

Excavators also found a distinct rectangular stone doorway and threshold stones that are geometrically consistent with entrances found in other Byzantine churches. Mosaic floor fragments further support the religious use of the site, even though many remain buried beneath layers of soil.

The rediscovery of Tharais comes at a time when the region is experiencing rapid urbanization. El-‘Iraq continues to expand with new roads and housing developments. Archaeologists caution that unless preservation efforts are implemented, crucial layers of historical evidence may be lost.

“Our aim is not just to uncover Tharais, but also to advocate for the protection of Jordan’s rich cultural heritage,” notes Al-Rawahneh.

The site’s inclusion in ongoing epigraphic and archaeological surveys in southern Jordan is expected to bring more clarity about its role and evolution through time. Further digs may reveal deeper insights into the daily lives, trade patterns, and religious rituals of its ancient inhabitants.