Anatolia’s ports, farms, roads and mints knit the eastern provinces into an imperial market that fed cities, provisioned armies, and sustained urban life across centuries, according to an academic study.

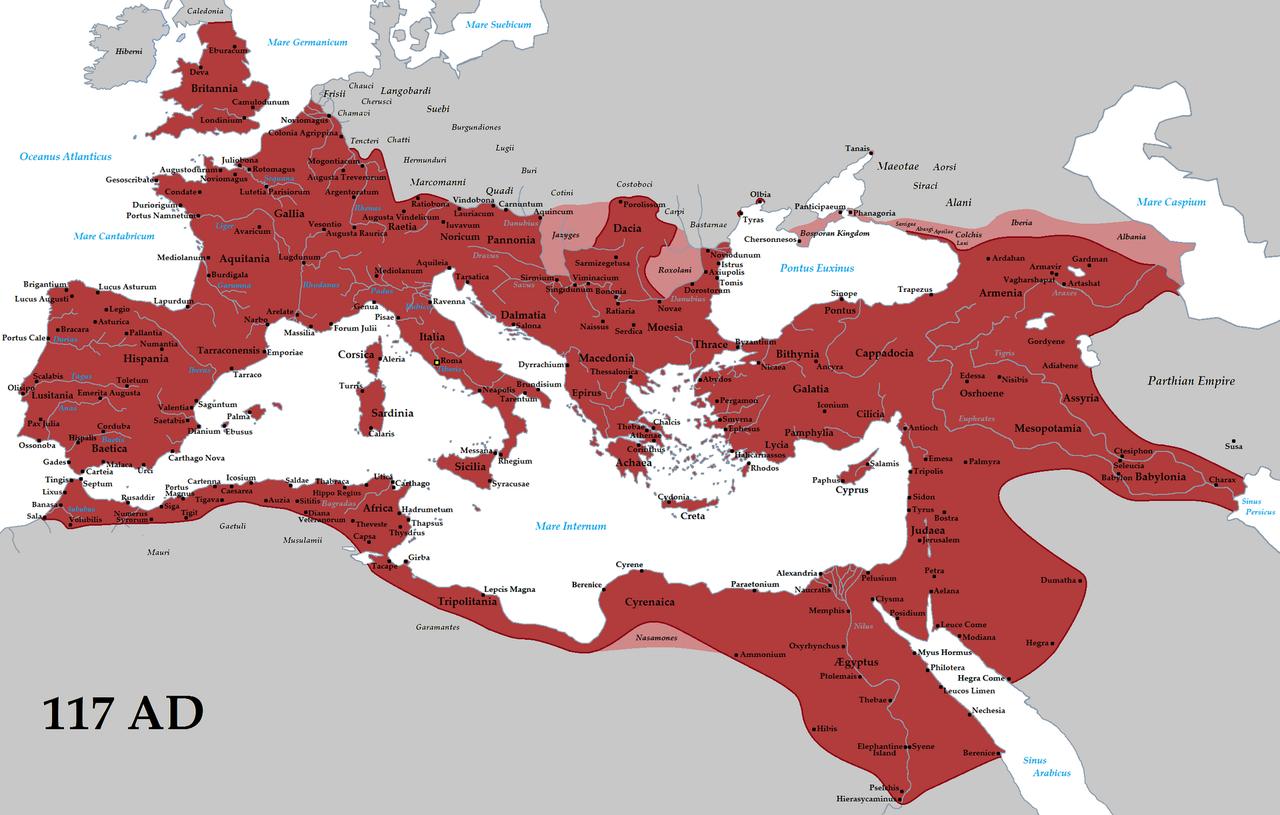

The article, published in the Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology, by Kublay Kocak of Babes-Bolyai University, sets out how Anatolia—modern-day Asian Türkiye—plugged into Rome’s fiscal, legal and transport systems from the bequest of Pergamon in 133 B.C. through Late Antiquity.

It highlights an east-west land bridge bordered by three seas, where ports such as Ephesus, Smyrna, Miletus, Side, Sinope and Trapezus sat on busy sea lanes while roads like the Via Sebaste linked inland basins to the coast.

The study describes agricultural heartlands that turned out cereals, olives and wine in the Aegean valleys and central plateau, alongside flax, cotton and citrus in Cilicia and timber and nuts on the Black Sea, with presses, storage and irrigation pointing to organized, market-oriented production.

It notes villae rusticae (rural estates) and smallholder farms feeding urban markets, with macella (food markets), horrea (warehouses) and standardized shop fronts shaping daily trade in cities such as Ephesus, Perge and Sagalassos.

| Tax Type | Latin Name | Rate/Amount | Collection Frequency | Application in Anatolia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Tax | Tributum soli-solisoli | 1% – 10% of value/product | Annually | Controlled by provincial governor |

| Head Tax | Capitatio cap. | Fixed amount | Annually | Variable depending on the city |

| Customs Duty | Portorium | 2% – 5% of value | Per transaction | In port cities and provincial borders |

| Sales Tax | Centesima | 1% of value | Per transaction | In local markets |

| Inheritance Tax | Vicesima | 5% of inheritance | After inheritance | Only for Roman citizens |

Source: Mitchell, S., Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor (Oxford University Press)

According to the article, integration rested on predictable taxation—land, head and customs dues—alongside a shared monetary framework. It lists portoria (customs duties) commonly in the low single digits, a 1% sales tax (centesima) and a 5% inheritance tax (vicesima), noting provincial application through Roman governors and local administrations.

On coinage, imperial mints at Nicomedia (modern Izmit), Cyzicus and later Constantinople issued gold, silver and bronze, while civic mints at Ephesus, Pergamon, Smyrna, Laodicea and Antioch supplied regional needs; coin hoards track moments of strain. Banking by private money-changers and temples supported exchange and credit.

Amphora evidence—such as Cilician Dressel 24 for olive oil and Aegean Kapitan II for wine—shows how goods moved around the Mediterranean, with Anatolia exporting agricultural produce, textiles, ceramics, glass, marble, metals and timber, and importing fine wares, papyrus and eastern luxuries like silk and spices. Underwater finds and harbor works round out a picture of steady seaborne traffic that cities organized and taxed.

The research traces shocks in the third century A.D. and points to fiscal and monetary reforms under Diocletian and Constantine, as well as the founding of Constantinople in 330 A.D., which shifted demand toward the Marmara and reinforced the region’s role. It adds that Christian institutions entered the urban economy as euergetism gradually gave way to new charitable structures.

Placing Anatolia within wider scholarly debates, the study contrasts the “embedded economy” view with models that stress market behavior and cites Peter Bang’s “imperial market” approach, while drawing on archaeobotany, ceramics, numismatics, epigraphy and GIS to back up its case. It concludes that Anatolia was not a passive periphery but a resilient economic powerhouse of the Roman world.