Two charred textile fragments unearthed at Beycesultan, a prominent archaeological site in western Türkiye, have revealed the earliest known use of indigo dye and a sophisticated yarn-looping technique called nålbinding in the region.

These findings offer rare insight into the textile technology, economic networks, and social structures of Bronze Age Anatolia.

According to a recent study, this rare find rewrites the narrative of Bronze Age textile production, illuminating how ancient societies in Anatolia mastered both complex dyeing techniques and advanced fabric-making methods nearly four millennia ago.

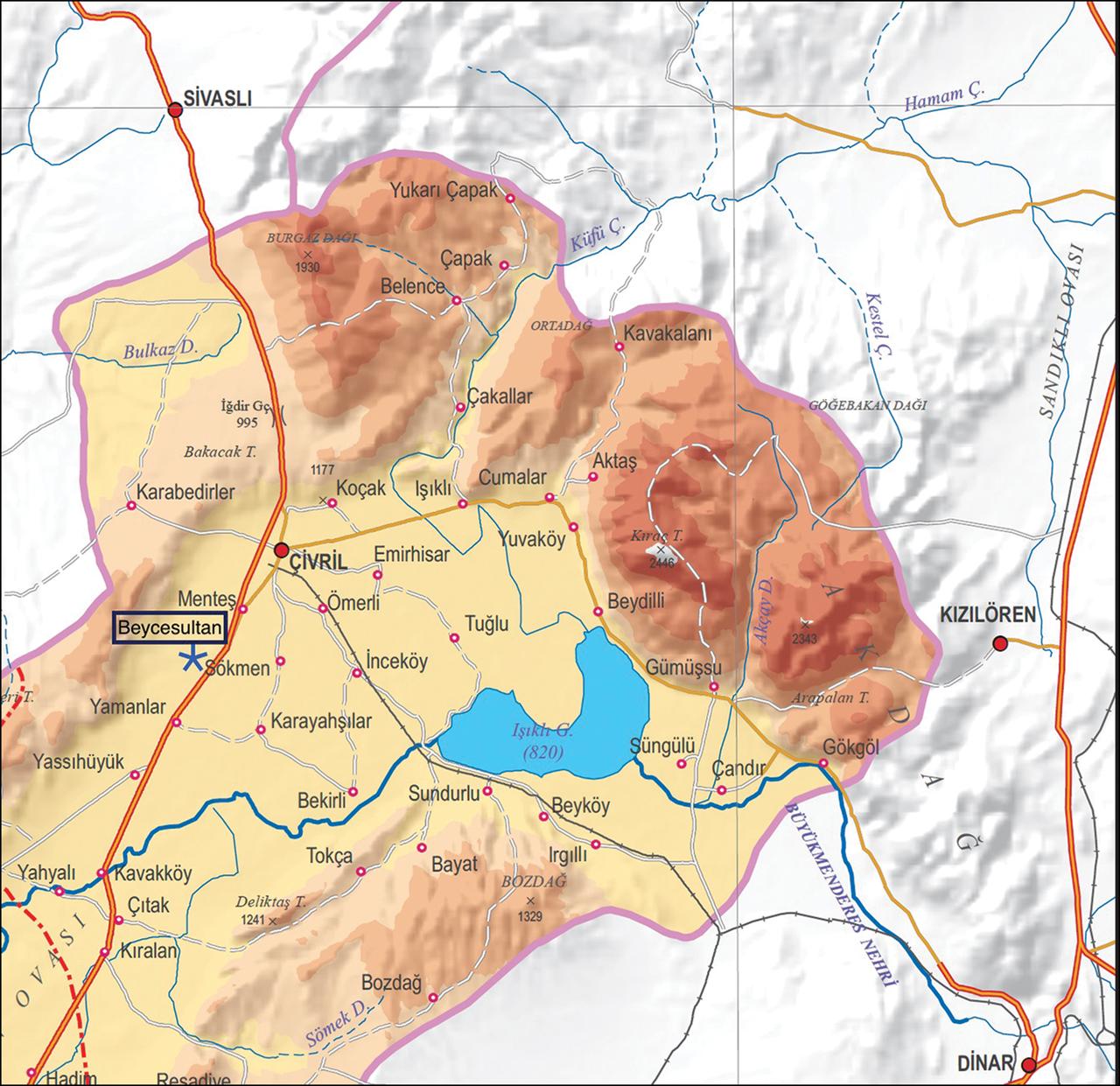

Beycesultan, located in the Denizli province and extensively excavated since the 1950s, spans layers from the Late Chalcolithic to the end of the Bronze Age.

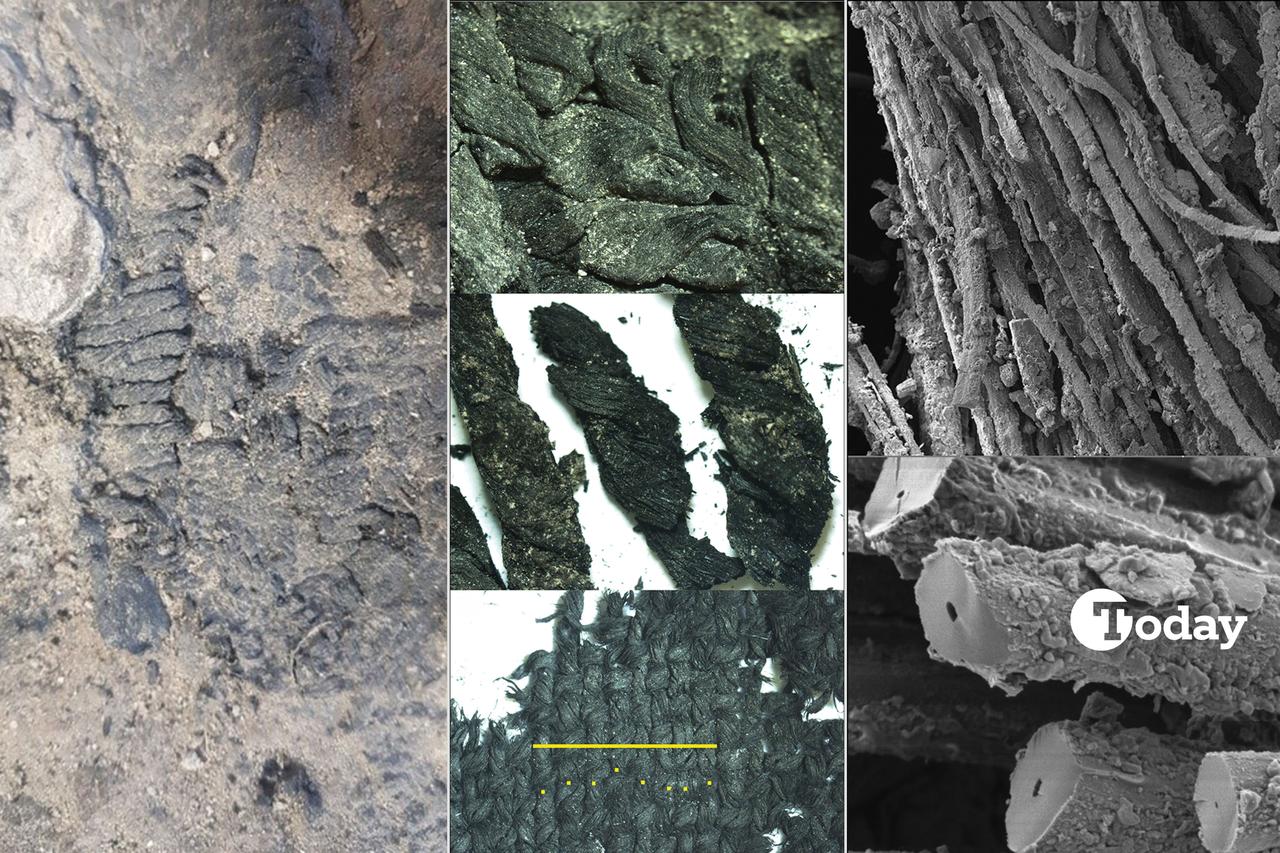

During renewed excavations between 2007 and 2018, archaeologists recovered two textile fragments—referred to as Tx1 and Tx2—from layers dated between 1,915 and 1,595 B.C. These were preserved due to intense fire damage that carbonized the materials.

The first textile, Tx1, was found in a courtyard-like space possibly linked to an elite or ceremonial building.

The second, Tx2, was recovered from what appears to be a domestic workshop room containing over 40 spindle whorls, several loom weights, and a range of tools associated with weaving.

Tx1 represents a form of early single-needle looping known as nalbinding. Unlike modern knitting, this technique uses individual pieces of yarn looped and knotted using a flat, blunt needle.

Although known from Neolithic Israel and later Egyptian examples, this is the first tangible evidence of its application in Anatolia. The yarn used in Tx1 was Z-twisted and about 2.25 millimeters thick, likely made from hemp fibers—an unusual choice in the textile history of the region.

Advanced chemical analysis using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) confirmed that Tx1 was dyed with indigotin, the compound found in natural indigo and woad. This makes it the earliest example of blue-dyed fabric ever found in Anatolia.

Cuneiform texts from Mesopotamia and Hittite Anatolia show that blue garments were highly prized and associated with elite status.

The dyeing of yarn with indigotin required sophisticated knowledge of vat fermentation techniques, further suggesting the prominence and specialization of Beycesultan’s textile production.

The second fragment, Tx2, exhibits a plain tabby weave pattern. While no dye traces were detected, SEM imaging suggests that the threads were likely made of plant fibers—possibly hemp, still cultivated in the region today.

If confirmed, this would be the oldest known hemp-based tabby weave in Late Bronze Age Anatolia.

The concentration of textile tools around Tx2—spindle whorls, loom weights, weaving combs, and needles—suggests that Beycesultan had an established and possibly specialized textile industry.

Archaeobotanical evidence and experimental reconstructions indicate that variations in whorl weight and loom weight thickness influenced the type and quality of fabrics produced.

Beycesultan’s textiles find parallels in sites such as Acemhoyuk and Seyitomer Hoyuk in central Türkiye, where other colored and patterned textiles have emerged.

Blue and red-dyed garments, sometimes found in palatial contexts or graves, point to widespread demand for luxurious fabrics during the Bronze Age.

The arrival of nalbinding and the use of indigo in Beycesultan suggest not only advanced local production but also connections with other regions such as the Caucasus, where similar textile impressions have been found.

These textiles, alongside the architectural and material evidence, support the interpretation of Beycesultan as a regional hub within a broader socio-economic and trade network.

No cuneiform tablets have been found at Beycesultan yet, leaving its ancient name unknown.

But these discoveries suggest the site may have served as a regional textile production hub, possibly supplying elite classes across Anatolia and beyond.