New research has shed light on how the world’s earliest farming villagers formed stable, inclusive communities across prehistoric Syria. Archaeologists from the University of Liverpool, Oxford, and Durham examined chemical traces in the teeth of 71 individuals who lived between roughly 11,600 and 7,500 years ago, during the Neolithic period—the era when humans first began to cultivate crops and raise animals.

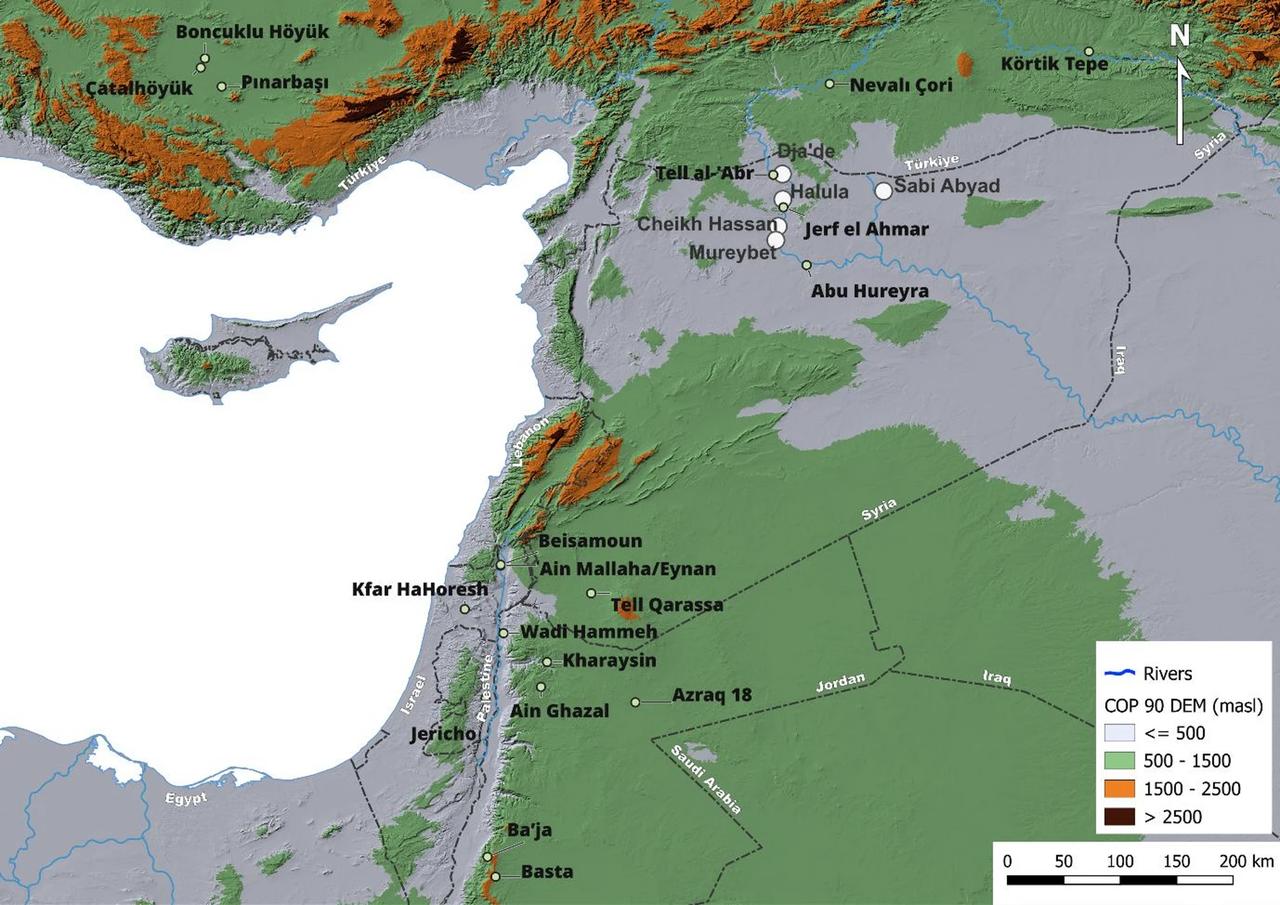

The team analyzed teeth from five ancient settlements in northern Syria—including the well-known site of Tell Halula—using strontium and oxygen isotope techniques. These chemical markers reveal where people grew up, allowing scientists to distinguish between locals and migrants.

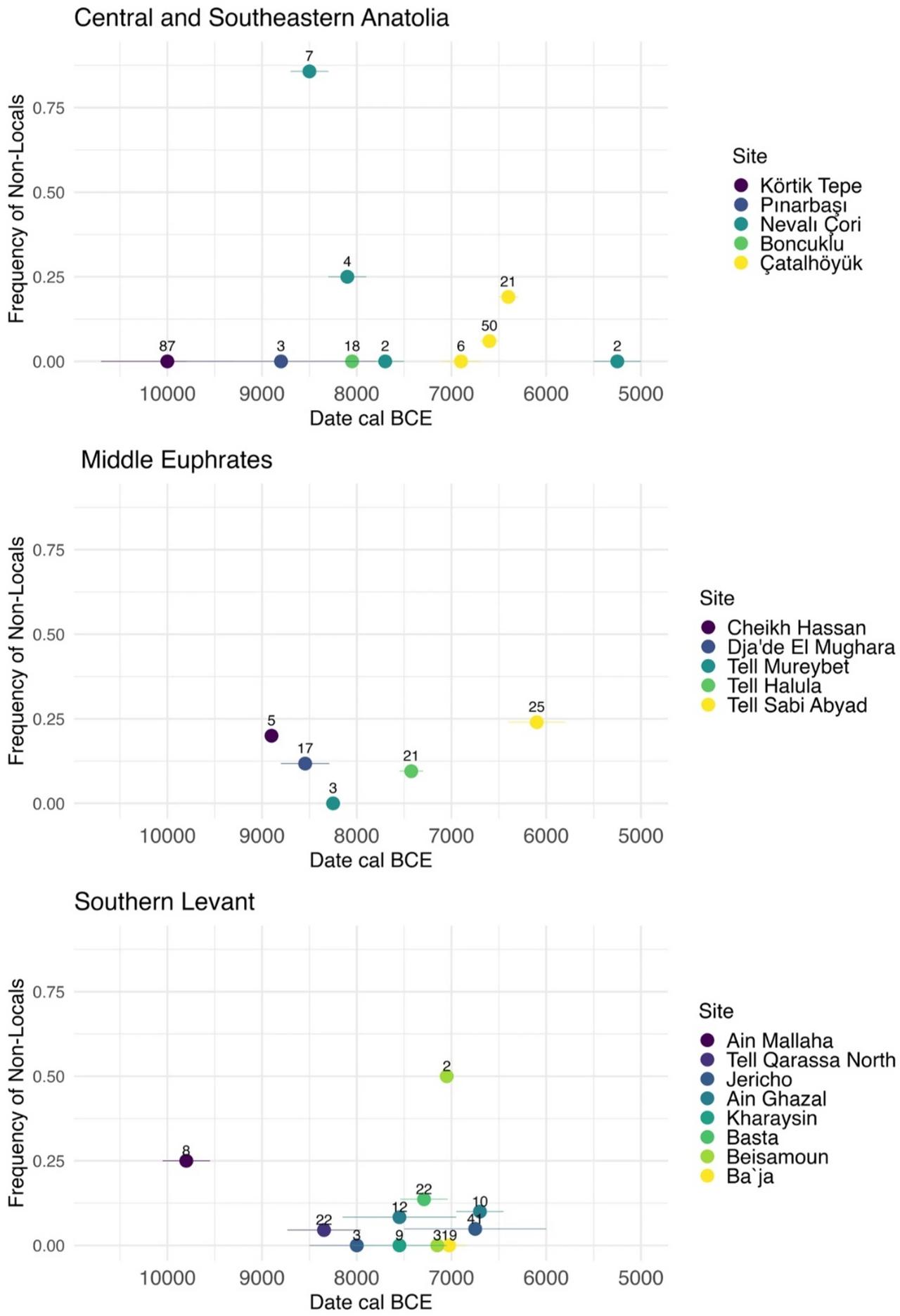

Findings show that once permanent villages were established, most residents stayed in one area for life. People gradually developed strong local identities and deeper emotional ties to their communities. The results also indicate that mobility decreased as agricultural life took hold, with later groups showing more stable, place-bound lifestyles.

According to Jo-Hannah Plug, now at Oxford University, and Professor Jessica Pearson from the University of Liverpool, this trend marked a critical social shift—one in which belonging and community identity became central to daily life.

Interestingly, by the later Neolithic, women appear to have been more likely than men to move between settlements. Researchers suggest that this pattern may reflect patrilocal traditions, in which women joined their husbands’ communities after marriage—a social system designed to prevent inbreeding within villages.

At sites like Tell Halula and Sabi Abyad, both local and non-local individuals were buried together and received similar funerary treatments. Graves sometimes contained elaborate offerings and shared resting places, showing that even outsiders were fully accepted into local society.

The study also points to a surprising degree of openness. At Tell Halula, archaeologists discovered locals and migrants interred side by side beneath house floors—a unique Neolithic practice linking homes with ancestry. Similar patterns at other sites suggest that newcomers were integrated both in life and in death, strengthening community bonds.

These inclusive practices, researchers believe, helped early agricultural societies survive and thrive by blending different cultural and genetic backgrounds.

Through detailed isotopic mapping, the team reconstructed life in early settlements where agriculture and animal domestication were taking root. Their results, published in Scientific Reports, reveal a society that managed to balance permanence with mobility—maintaining deep local roots while staying open to outsiders.

By analyzing the enamel of ancient teeth, archaeologists have now filled a critical gap in our understanding of how humanity’s first farming villages emerged, endured, and evolved into the complex communities that eventually shaped civilization.