Cinema arrived in the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the 20th century as a powerful new visual medium. Drawing on existing traditions of spectacle, it quickly spread across Istanbul and beyond, sparking debates over morality, gender, childhood and state control while reshaping urban spectatorship and public life.

Cinema did not enter Ottoman society as a sudden rupture. As Canan Balan argues in her academic work on spectatorship and modernity in late Ottoman Istanbul, urban life itself had long been understood as a form of spectacle.

Traditional entertainment practices, such as Karagoz shadow plays, public storytelling, panoramas, dioramas and magic lantern shows, had already trained audiences to engage with projected images in collective settings.

According to Balan, this continuity explains why cinema was absorbed relatively smoothly into Ottoman cultural life. Early film screenings often took place during Ramadan festivities and shared venues with Karagoz performances, whose reliance on light, shadow, and motion bore striking technical similarities to early cinema.

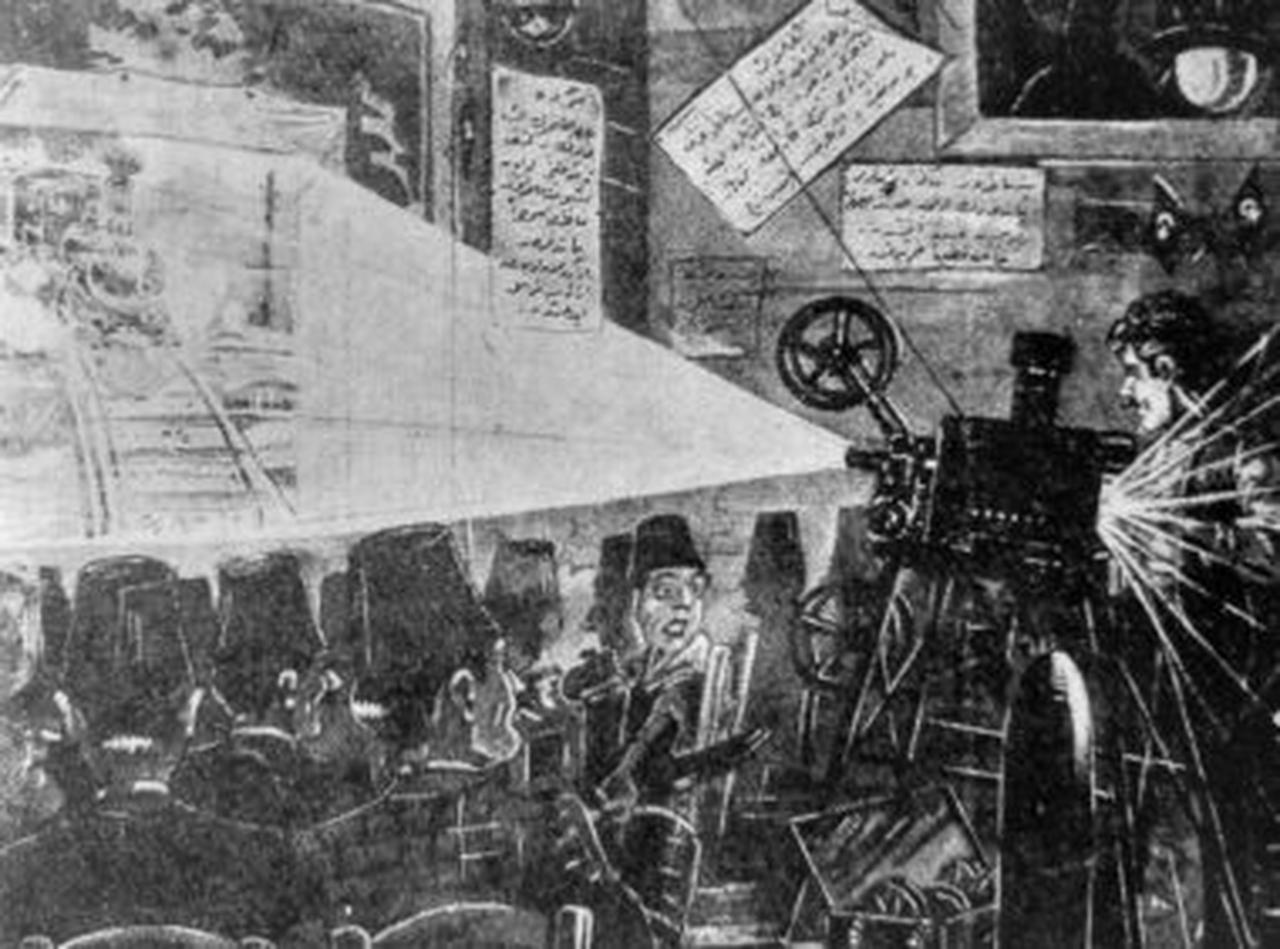

According to Professor Bilal Yorulmaz’s article on the history of cinema in the Ottoman Empire, the empire encountered cinematic technology almost immediately after its invention in the West.

Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope, developed in 1894, was brought to Istanbul the same year and exhibited in Beyoglu. Similar exhibitions followed in Izmir at Apollon Hall and Luka Coffeehouse.

After the Lumiere brothers’ first public screening in Paris in December 1895, their cinematograph reached Ottoman territories within months.

A September 1896 Ottoman report described the cinematograph as “an important tool for the dissemination of information for humankind,” a definition that helped legitimize the device in official circles. Sultan Abdulhamid II himself watched cinematograph screenings in 1896.

One of the earliest public screenings took place on January 16, 1897, at the Sponeck Beerhouse in the Galatasaray neighborhood.

The event was organized by Sigmund Weinberg, a Polish Jewish entrepreneur who would become a central figure in Ottoman cinema history.

As documented in Yorulmaz’s study, Weinberg later represented the French Pathe company and opened the Pathe Cinema in Tepebasi in 1908, the first permanent cinema hall in the empire.

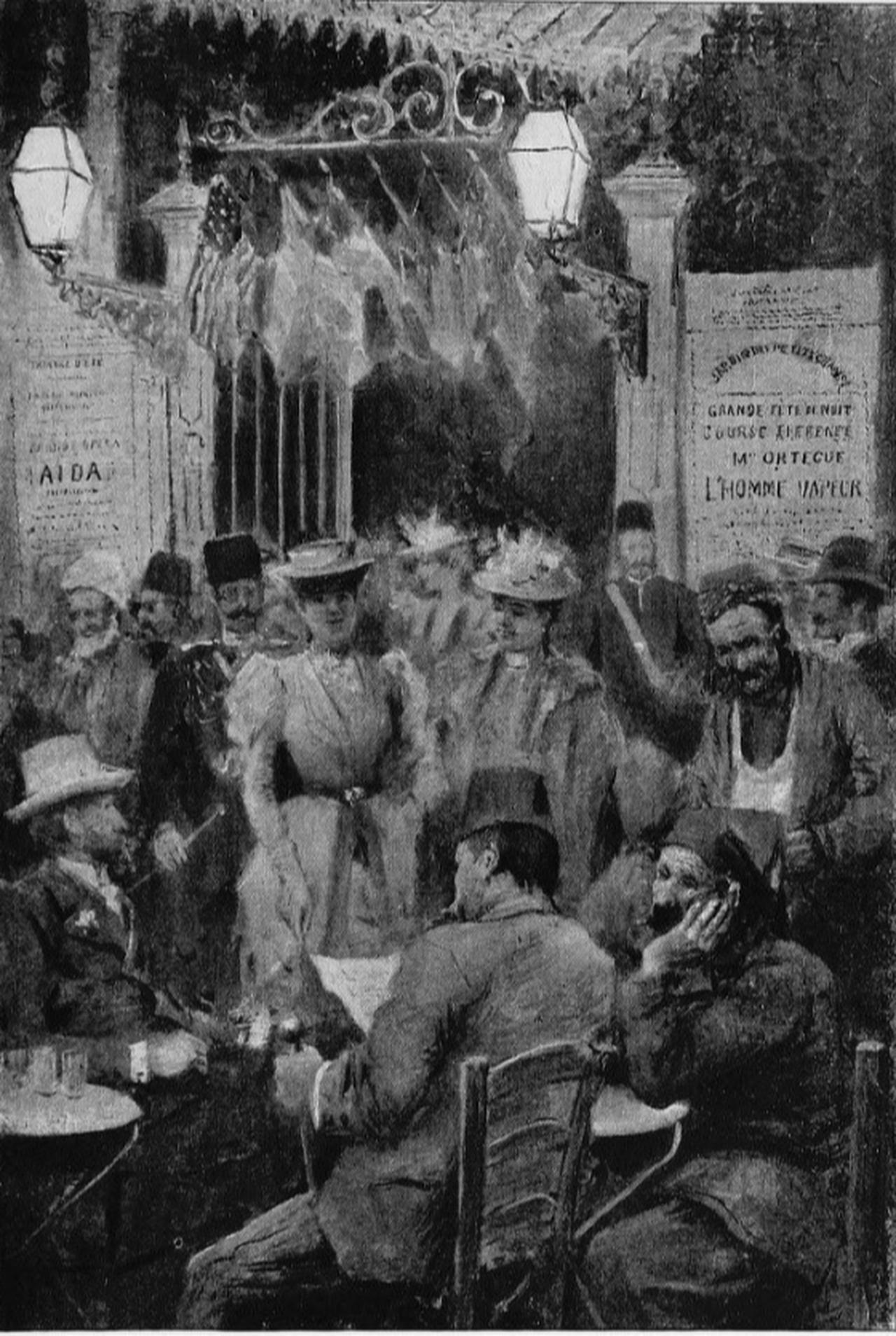

By the early 20th century, cinema halls had become established features of urban life in Istanbul and other major cities, attracting diverse, multiethnic audiences while reinforcing class distinctions through ticket prices and seating arrangements.

Cinema’s growing popularity quickly triggered moral debates, particularly around women’s attendance. Yorulmaz records numerous petitions submitted by citizens, especially in Izmir, calling for Muslim women to be banned from cinemas.

Izmir Governor Celal Bey temporarily restricted women’s access following public pressure, while Beirut Governor Ethem Bey rejected similar demands, illustrating the lack of a standardized imperial policy.

Despite widespread concern, no Islamic legal ruling prohibited women from attending cinemas. Sultan Resad even allowed women of the imperial harem to attend screenings. In practice, gender segregation was often maintained through women-only sessions or physical divisions within cinema halls, such as folding screens.

Concerns over children were more forcefully institutionalized. A 1916 expert report prepared by Ahmet Bey, Director General of Public Security in Istanbul, warned that cinemas, many of which were combined with cafe-chantants, posed moral and psychological dangers to minors.

The report argued that violent and erotic scenes could traumatize children, normalize brutality, and encourage criminal tendencies.

These concerns directly influenced policy. In August 1916, amendments to the Regulation on the Establishment and Administration of Theater, Cinema, and Similar Entertainment Places formally prohibited children under the age of 16 from attending cinema screenings.

Beyond moral panic, cinema transformed how cities were seen and experienced. In her analysis, Canan Balan draws on Judith Walkowitz’s work on urban spectatorship, particularly her critique of the romanticised flaneur, to highlight the inequalities embedded in modern visual culture.

Walkowitz describes a city marked by slums, “dark and noisy courts,” and limited access to spectacle for the poor. Balan applies this framework to late Ottoman Istanbul, arguing that modern spectatorship turned the city into a landscape of strangers and secrets, prompting greater state intervention.

Invoking Michel Foucault’s concept of the Panopticon from Discipline and Punish, Balan interprets cinema as part of expanding surveillance mechanisms. Cinema halls were spaces of pleasure, but also sites of inspection, discipline, and control, reflecting the Ottoman state’s efforts to manage modern urban life.

Cinema assumed a new role during World War I. The Central Army Cinema Office (Merkez Ordu Sinema Dairesi, MOSD) was established to document military activities and produce propaganda films.

According to Yorulmaz, Weinberg was appointed director, with Fuat Uzkinay as his deputy. The office produced documentaries depicting the Gallipoli campaign, military drills, captured enemy officers, and visits by foreign leaders, including the German emperor.

In 1914, Uzkinay filmed The Destruction of the Russian Monument at Ayastefanos, widely regarded as the first Turkish-made film and a symbolic moment in Muslim Turkish engagement with cinema.

Narrative filmmaking developed cautiously. Weinberg began shooting Himmet Aga’nın Izdivaci in 1916, but the project was interrupted when he was dismissed due to his Romanian citizenship. Uzkınay completed the film in 1918.

At the same time, the National Resistance Organization (Mudafaa-i Milliye Cemiyeti) produced films such as Pence and Casus to raise funds.

As Yorulmaz notes, Pence provoked controversy for portraying marriage as oppressive and depicting extramarital relationships, making it one of the earliest Ottoman films to spark moral debate.

By the final years of the Ottoman Empire, cinema had become firmly embedded in urban life, regulated, politicized, and deeply contested.

It functioned simultaneously as entertainment, propaganda, surveillance, and social critique.

The Ottoman encounter with cinema was not a passive imitation of Europe but a complex process of negotiation shaped by tradition, modernity, and state power.

As the empire gave way to the Turkish Republic, cinema would be reimagined once again, but its Ottoman foundations reveal how moving images first transformed public life through spectacle, scrutiny, and the watchful gaze of the modern state.