In the National Museum of Ravenna sits an object that defies simple categorization: a massive 16th-century circular leather table. A rare masterpiece of Ottoman craftsmanship, it is a canvas of gilded Turkish, Persian and Latin inscriptions.

As art historian Elisa Emaldi’s research reveals, this table is more than furniture; it is a silent witness to how the Ottoman elite wove food, faith, and political power into a single, circular ritual.

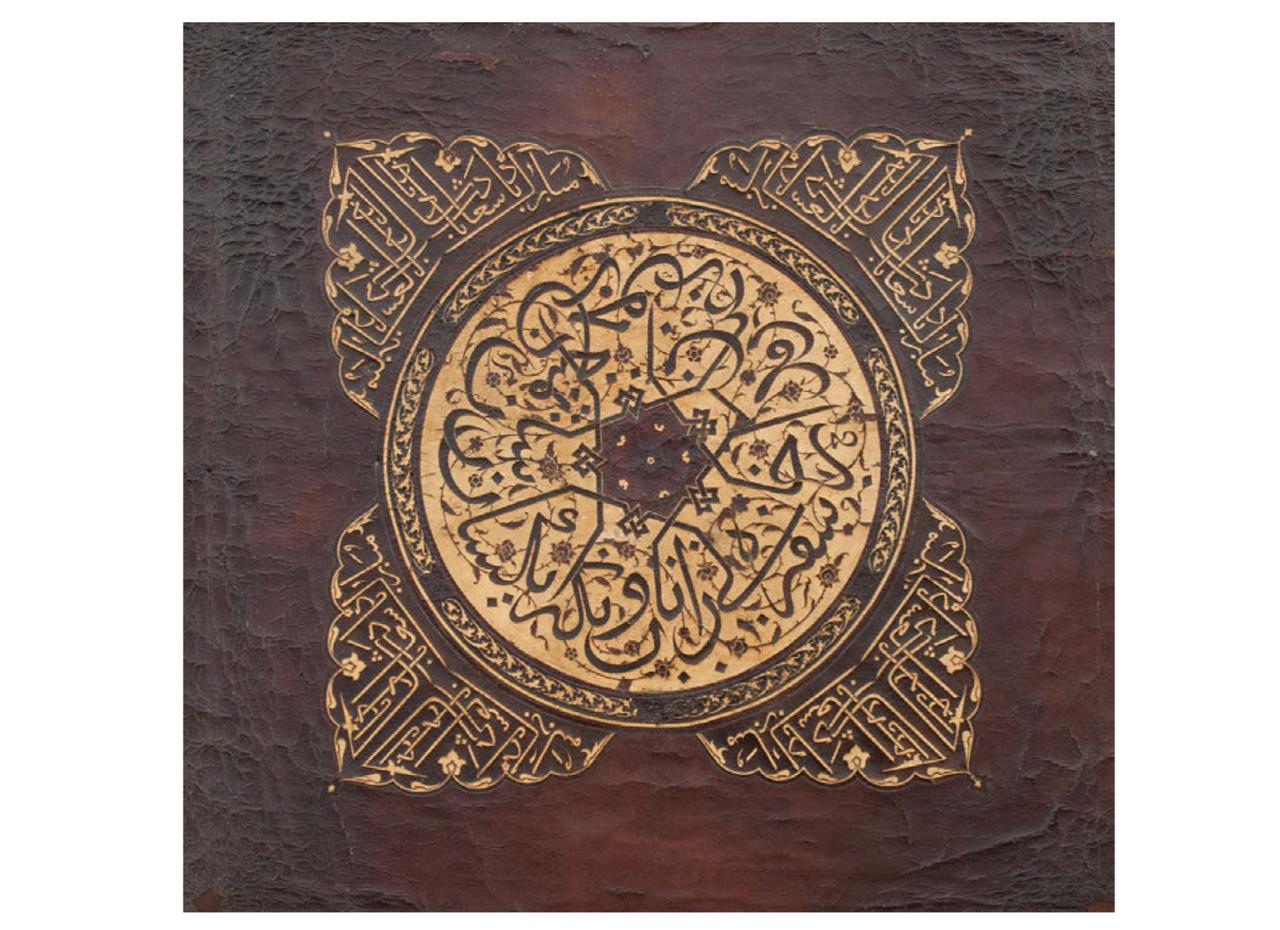

The object is known as a sofra, a term used in Ottoman Turkish to describe a dining surface placed directly on the floor. A sofra was not simply a table but a movable dining mat or platform around which food was shared, often during travel or military campaigns. The example in Ravenna, made of gilded leather stretched over a wooden support, measures about 2 meters in diameter and was produced in the second half of the 16th century.

Leather sofra were more expensive and more durable than textile ones, which made them suitable for long journeys and military use. Because Islamic sumptuary laws limited the use of silk and precious metals, finely worked leather became an accepted way to signal prestige. As Emaldi explains through historical sources, such objects were especially associated with high-ranking figures, likely including an Ottoman pasha, a title given to senior imperial officials.

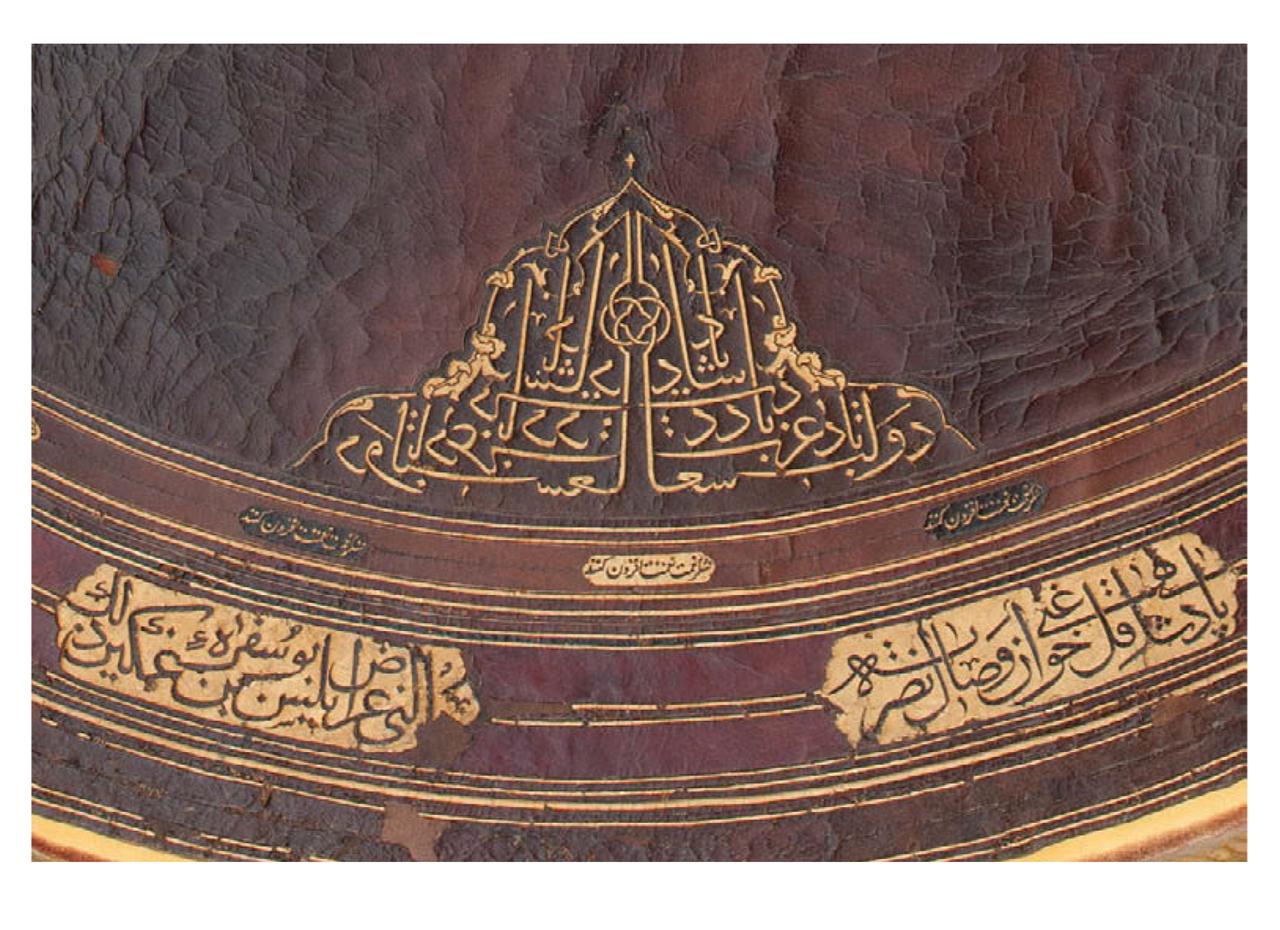

What makes the Ravenna sofra particularly rare is its dense program of inscriptions, executed in an elaborate kufic-inspired calligraphy that earlier scholars described as extremely complex. Along the outer band, 12 Turkish inscriptions invoke divine grace, abundance, long life for the ruler, and victory, addressing the table itself as if it were a living participant in the act of dining.

Moving inward, Persian inscriptions repeat a formula that links gratitude to increased divine favor.

Persian was widely used as a literary and artistic language across the Ottoman world, even though it was not the everyday spoken tongue. At the center, Latin phrases such as Quod felix bonum faustum fortunatumque sit express wishes for good fortune, while a final invocation urges that the table never be without food and always remain attentive to delights.

The sofra entered Italy through channels that remain partly unclear. It was likely acquired by the Camaldolese monks of Classe near Ravenna, either through the antiquities market, diplomatic exchange, or as war booty during conflicts between European powers and the Ottoman Empire. By the late 19th century, it had become part of the National Museum of Ravenna, where it is now displayed.

The piece was first studied in detail in the mid nineteenth century by Orientalist Michelangelo Lanci, but Emaldi notes that later scholarship, especially translations completed in the late 20th century, has significantly revised earlier interpretations and clarified the object’s cultural context.

Very few leather sofra have survived to the present day. Comparable examples are known from the Topkapi Palace collection in Istanbul and from the Habsburg collections in Austria, underscoring how exceptional the Ravenna piece is in terms of size, craftsmanship, and preservation.

As Emaldi concludes, the sofra should be understood not just as a utilitarian object but as a ceremonial monument, one that reflects how dining practices, religious language, and political authority came together in the Ottoman world. Its survival allows modern audiences to grasp a material expression of power that once traveled with imperial elites across continents.