Archaeologists say there is little evidence that a lethal epidemic ever struck Akhetaten—ancient Amarna—the short-lived 14th-century B.C. capital founded by Pharaoh Akhenaten.

A comprehensive reassessment by Gretchen Dabbs and Anna Stevens, published in the American Journal of Archaeology, challenges a theory long fueled by Hittite plague prayers that blamed Egyptian captives for spreading a deadly disease across Anatolia. The study compares what epidemics typically leave behind with what is actually visible in Amarna’s cemeteries and settlement layers—and the patterns do not match an outbreak with high mortality.

Akhetaten (today's Amarna) was built by Akhenaten—formerly Amenhotep IV—who elevated the sun god Aten as the primary state deity and moved his court to a purpose-built city that was occupied for about two decades. For years, scholars floated the idea that an epidemic explained both Akhenaten’s unusual decisions and the city’s rapid decline.

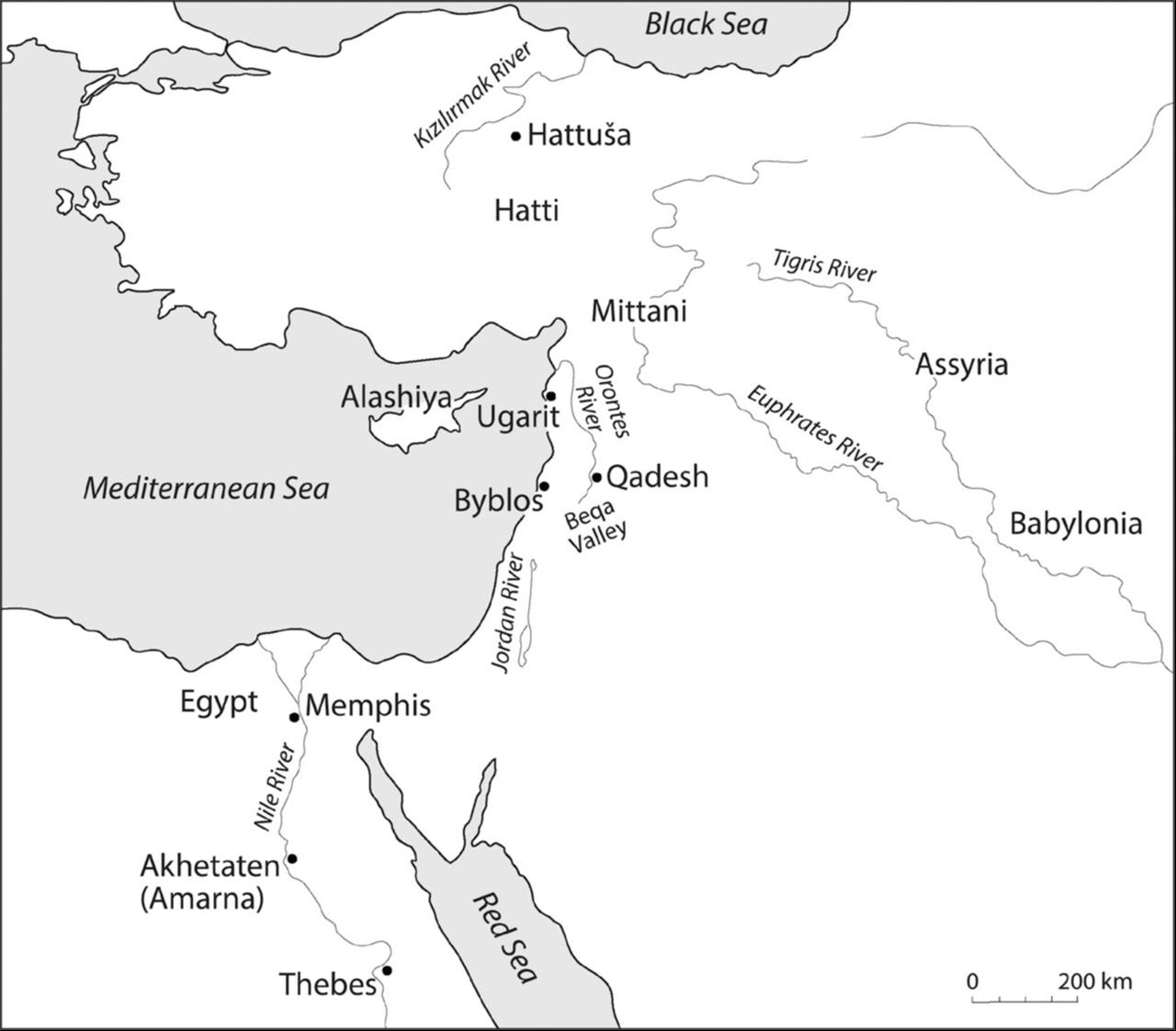

Textual hints exist in the wider region—the Hittite “plague prayers” and several Amarna Letters mention disease in places like Megiddo, Byblos, and Sumur—but none of these sources actually claims a plague inside Akhetaten itself. The new paper, therefore, tests Amarna’s on-site archaeological and bioarchaeological record against expectations for an epidemic city.

Four burial grounds for the general populace—the South Tombs, North Cliffs, North Desert and North Tombs Cemeteries—likely hold 11,350–12,950 people; 889 interments excavated between 2005 and 2022 underpin the analysis. Skeletons show heavy life stress (short adult stature, spinal trauma, enamel growth interruptions, joint disease), consistent with demanding work and economic strain.

Clear markers of infectious disease are scarce: tuberculosis has been identified in just seven individuals so far. Bodies—usually unembalmed—were placed with textiles, mat coffins, and occasional goods; burials were generally orderly rather than rushed, which is not what one expects during a city-wide mortality spike.

Researchers did note an unusual number of multiple burials, especially pairings. Yet demographic patterns—most often adult females with children—point to intentional, culturally shaped interments rather than emergency mass graves.

Where clustering appears (notably at the North Tombs Cemetery), it aligns with a narrowly aged, labor-intensive group that likely lived and died under extreme workloads. The team argues this reflects social organization and occupational stress, not a fast-moving epidemic.

Paleodemographic modeling shows the number of interments fits the city’s population and the short lifespan of the settlement.

Life expectancy and the length of occupation remain within expected ranges; in an epidemic, one would anticipate a signature surge in deaths that overshoots those baselines.

Amarna’s end does not resemble a city emptied by disease. Evidence indicates a systematic draw-down after Akhenaten’s death, with possessions collected and some continued, lower-level occupation—again not the archaeological footprint of panic or collapse driven by contagion.

As the authors put it, once expectations from known epidemic sites are applied to Amarna, “what we actually see doesn’t fit the expected models.”

The study stresses that a Hittite epidemic may well have occurred, and Egyptian prisoners could have been implicated in its spread elsewhere.

But for Amarna itself, the “plague” narrative grew from circumstantial links: clustered royal deaths, references to disease in far-off letters, and the later repetition of a compelling idea without on-site proof. The new synthesis urges caution when importing texts from different places and times to explain a single ancient city.