Scientists have extracted and sequenced the oldest known Egyptian DNA from a man who lived between 4,500 and 4,800 years ago—during the era of the first pyramids—according to research published Thursday in Nature.

For the first time, researchers from the Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) have decoded the full genome of an ancient Egyptian, offering new insights into the origins and diversity of one of history’s most fascinating civilizations.

The individual's body was first recovered from a tomb in Nuwayrat, in Upper Egypt, in 1902, and now reveals new information about the genetic makeup of early Egyptians. Before this analysis, only three ancient Egyptian genomes had been sequenced, and all were partial.

The DNA came from the teeth of a man who lived around 4,500 to 4,800 years ago during Egypt’s Old Kingdom. His remains were discovered inside a sealed ceramic jar in a rocky tomb near Nawareet, south of modern-day Cairo.

Despite Egypt’s hot climate, which usually degrades ancient DNA, his DNA was remarkably well preserved. Scientists suspect the unusual nature of the burial may have helped the DNA survive the past four millennia.

Interestingly, the man was buried without mummification, a departure from the famous Egyptian embalming tradition, which likely helped preserve his teeth and DNA.

Analysis shows that about 80% of his ancestry traces back to North African populations, while around 20% connects to groups from the eastern Fertile Crescent, including the Levant and Mesopotamia, now part of modern-day Iraq, Iran and Syria.

This finding supports archaeological evidence of close cultural and trade ties between ancient Egypt and its neighbors.

Experts say this genome sheds light on the rich genetic tapestry of ancient Egypt, showing it was a melting pot of regional influences rather than a population isolated from its surroundings.

Researchers hope to sequence more ancient Egyptian genomes to build a clearer picture of how populations in the region changed over millennia. This work could transform our understanding of the genetic history not only of Egypt but of the broader ancient world.

By analyzing chemical signals in his teeth related to diet and environment, researchers concluded the man likely grew up in Egypt.

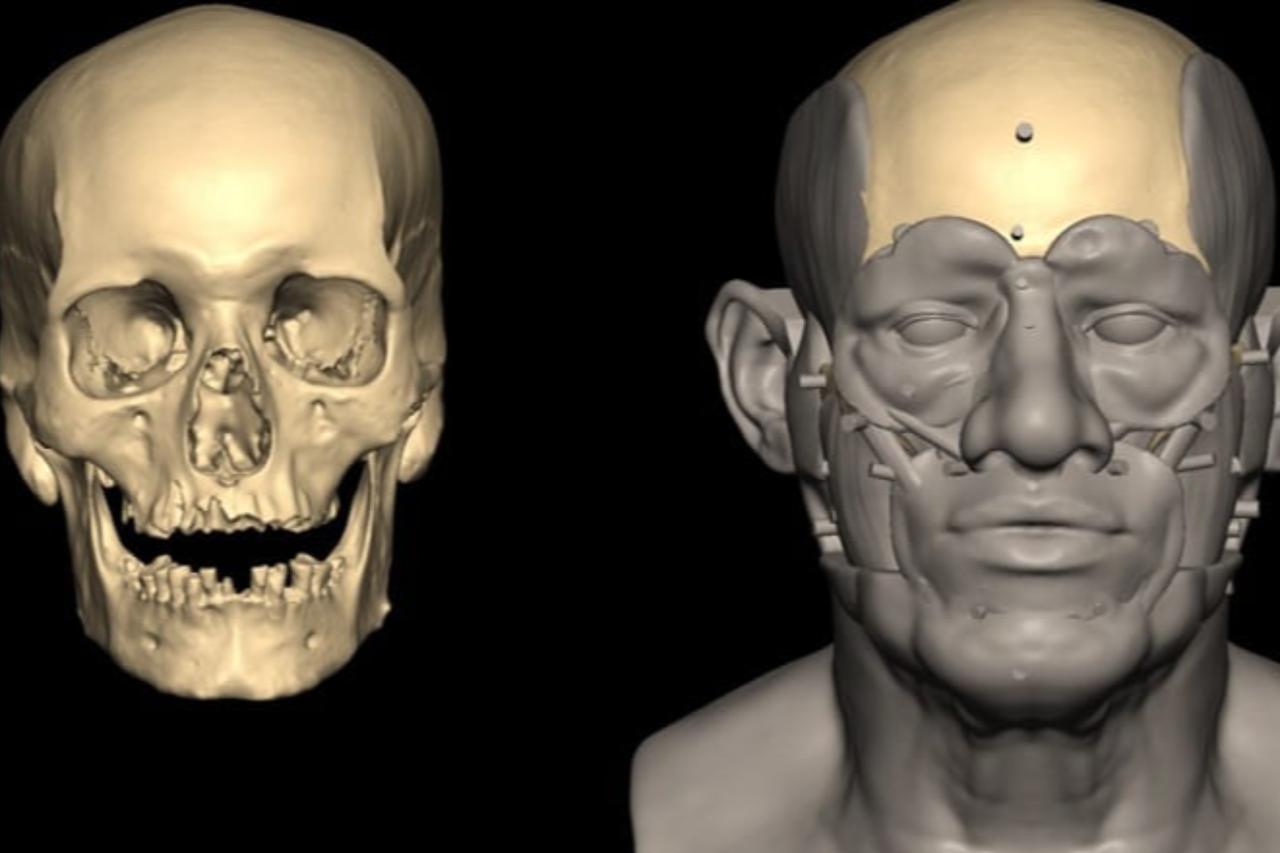

They examined his skeleton to estimate his sex, age, height, ancestry, and lifestyle. Muscle markings on his bones indicated long periods of sitting with outstretched limbs, suggesting he may have worked as a potter or in a similar trade.

Professor Irish explained, “The skeleton shows clues about his life—enlarged seat bones, arms with signs of repeated movement, and arthritis in his right foot. Though circumstantial, these point to pottery work, including the use of a pottery wheel, which appeared in Egypt around that time.”

He must have held a prominent status to be buried in a rock-cut tomb,” the researchers noted. “That contrasts with the physical signs of a demanding life and the idea that he was a potter—a trade typically associated with the working class. He may have been a highly skilled artisan.”