Before its archaeological discovery was formally announced to the public, a reproduction of the newly uncovered “Good Shepherd” fresco from Iznik had already entered the realm of high-level diplomacy.

During his visit to Türkiye marking the 1,700th anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan presented Pope Leo XIV with a ceramic reproduction of the fresco. The gesture, rooted in an excavation at the Hisardere Necropolis in ancient Nicaea, went beyond courtesy and was widely seen by experts as a carefully layered act of cultural diplomacy.

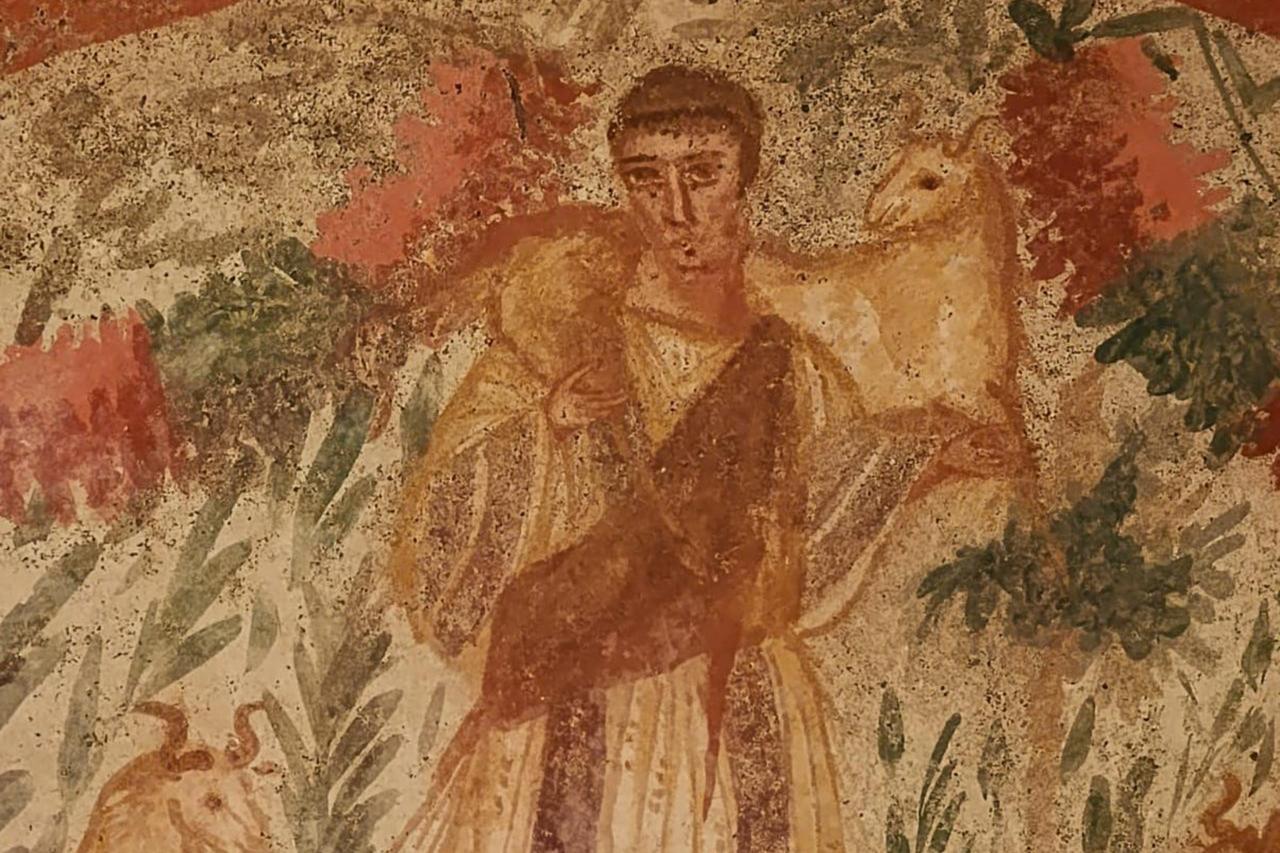

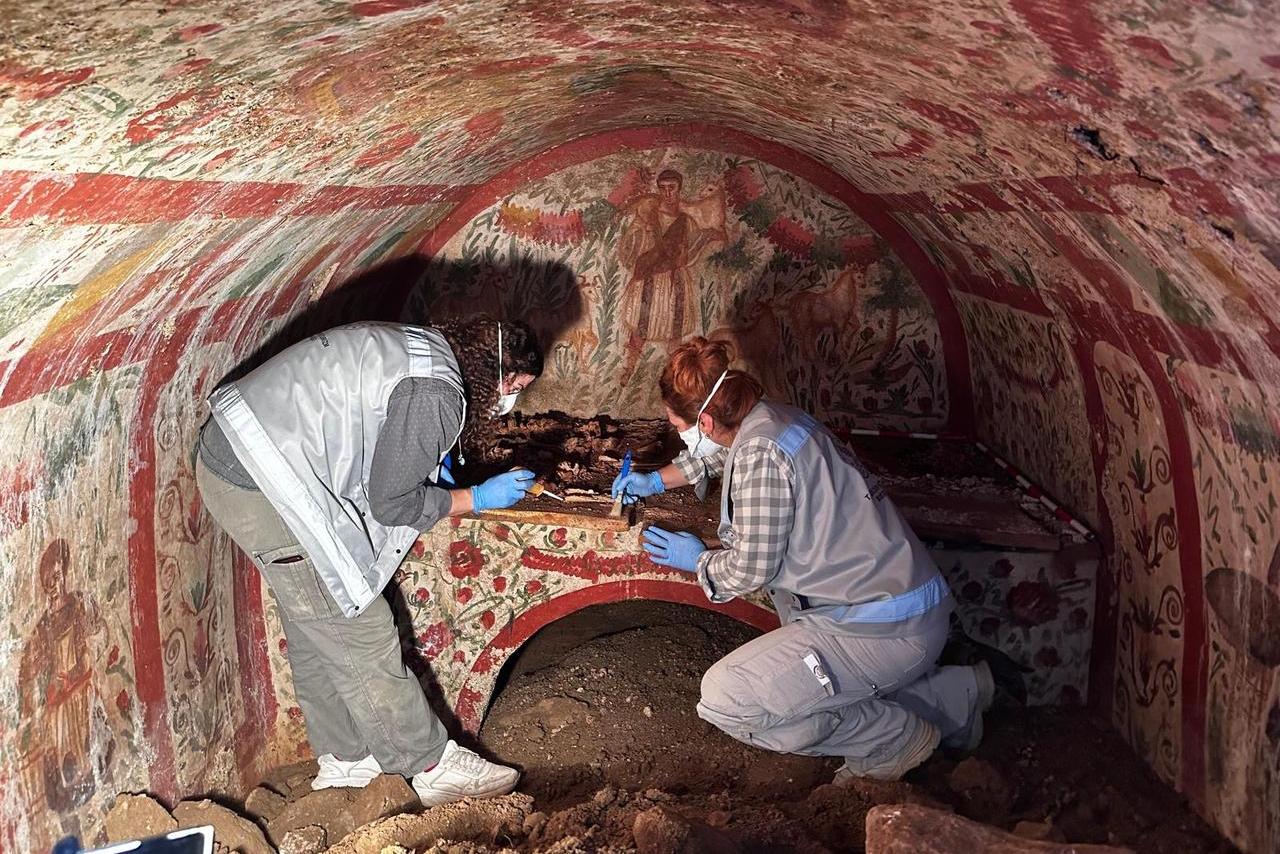

The fresco in question was uncovered in a chamber tomb at the Hisardere Necropolis in Iznik, the ancient city of Nicaea, a place central to Christian history as the site of the First Ecumenical Council in 325. The wall painting depicts Prophet Jesus as the “Good Shepherd,” a young, beardless figure carrying a goat on his shoulders, rendered in a clearly Roman visual style.

Archaeologists involved in the excavation have described the scene as the only known example of its kind identified so far in Anatolia. The tomb itself is dated to the third century based on architectural parallels within the same necropolis, placing it firmly within the Early Christian period. The fresco was found inside a hypogeum, or underground chamber tomb, a burial type common in the Roman world.

According to a Turkish art history scholar, presenting this image directly pointed to Iznik’s foundational role in Christian theology. By selecting an artwork from the geography where early Christian doctrine was shaped, the gift positioned Türkiye not merely as a host country but as a long-term guardian of lands central to Christian heritage.

The fact that the discovery represents the first known “Good Shepherd” fresco outside Italy further reinforced this message. Experts noted that the gesture implicitly conveyed that Türkiye does not only preserve historical layers, but also brings them to light and makes them visible to the wider world.

The subject of the fresco itself added another layer of meaning. Jesus is portrayed as a shepherd, an image shared across different belief systems as a symbol of care and guidance. The act of a Muslim-majority country’s leader presenting such an image to the spiritual leader of the Catholic Church was interpreted as a strong visual statement on interfaith tolerance.

Scholars also emphasized that the fresco reflects a transitional phase in which Christian iconography absorbed elements of earlier pagan symbolism, highlighting continuity rather than rupture in religious visual culture. This aspect, already underlined in archaeological evaluations, enhanced the diplomatic resonance of the gift.

The choice to present a ceramic reproduction rather than the original fresco was dictated by conservation laws and international norms. The reproduction, executed on traditional tile, referenced Turkish craftsmanship while ensuring the object remained durable and transportable.

Experts described the gift not only as symbolic but also as a tangible artistic object designed to endure.

Despite its largely positive reception, cultural diplomacy specialists also pointed to potential areas of debate. According to Assoc. Prof. Tuna Akcay, who spoke to Türkiye Today, such gestures often operate within a broader political context and may seek to support diplomatic narratives beyond culture alone. Others highlighted that international cultural messaging gains credibility only when matched by consistent heritage protection practices at home.

At the same time, the use of a reproduction, while legally necessary, was seen as limiting the material weight of the gesture, even as it amplified its symbolic reach. Some experts also observed that focusing solely on the “Good Shepherd” fresco left untapped opportunities to showcase other layers of Anatolia’s multi-period, multi-faith heritage.